If you are new to SQLite, you may well run across one of the most confounding of its implementation details the moment you attempt to do some sort of bulk or batch processing of inserts or updates.

What you will discover is that unless properly implemented, inserting or updating multiple records in a SQLite database can seem abysmally slow. Slow to the point of unsuitability in certain cases.

Not to fear, this has to do with some default (and not entirely improper) design choices in SQLite, for which there is an easy workaround.

Image by Lance McCord | Some Rights Reserved

SQLite is a wonderfully simple to use, cross-platform/open source database with terrific performance specs. It is a mature product, and, if we are to believe the estimates of SQLite.org, is the most widely deployed SQL database in the world.

SQLite manages to cram a host of mature, well-developed features into a compact and well-documented package, including full transaction support.

This transaction support, and the way it is implemented, has a significant impact on certain performance characteristics of SQLite.

Transactions by Default in SQLite

As stated previously, one of the selling points of SQLite, despite it being a simple, file-based database, is that it is fully transactional. What does this mean?

From Wikipedia:

A transaction comprises a unit of work performed within a database management system (or similar system) against a database, and treated in a coherent and reliable way independent of other transactions. Transactions in a database environment have two main purposes:

- To provide reliable units of work that allow correct recovery from failures and keep a database consistent even in cases of system failure, when execution stops (completely or partially) and many operations upon a database remain uncompleted, with unclear status.

- To provide isolation between programs accessing a database concurrently. If this isolation is not provided, the program's outcome are possibly erroneous.

A database transaction, by definition, must be atomic, consistent, isolated and durable.[1] Database practitioners often refer to these properties of database transactions using the acronym ACID.

Transactions provide an "all-or-nothing" proposition, stating that each work-unit performed in a database must either complete in its entirety or have no effect whatsoever. Further, the system must isolate each transaction from other transactions, results must conform to existing constraints in the database, and transactions that complete successfully must get written to durable storage.

SQLite is not alone, of course, in implementing transactions - in fact, transactions are a core concept in database design. However, the implementation of SQLite proposes that, unless otherwise specified, each individual write action against your database (any action through which you modify a record) is treated as an individual transaction.

In other words, if you perform multiple INSERTs (or UPDATEs, or DELETEs) in a "batch," each INSERT will be treated as a separate transaction by SQLite.

The trouble is, transactions carry processing overhead. When we decide we need to perform multiple INSERTs in a batch, we can run into some troubling performance bottlenecks.

If we are using SQLite from the SQLite Console, we can see exactly what I am talking about by running an easy insert script, and seeing how things go. For this example, I borrowed a few lines from the Chinook Database to create and populate a table of Artists. If you don't have the SQLite Command Line Console on your machine, install it now (see Installing and Using SQLite on Windows for details). Then copy the SQL script from my Gist on Github, paste it into a text file, and save the file in your user folder as create-insert-artists.sql.

The script should look like this in the text file before you save:

Paste the SQL Script Into a Text File and Save:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS [Artist];

CREATE TABLE [Artist]

(

[ArtistId] INTEGER NOT NULL,

[Name] NVARCHAR(120),

CONSTRAINT [PK_Artist] PRIMARY KEY ([ArtistId])

);

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (1, 'AC/DC');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (2, 'Accept');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (3, 'Aerosmith');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (4, 'Alanis Morissette');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (273, 'C. Monteverdi, Nigel Rogers');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (274, 'Nash Ensemble');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (275, 'Philip Glass Ensemble');

If we open a new database in the SQLite Console (navigate to your User folder to do this for our purposes here) and read the script, we can see how long it takes. There are 275 Artist records in the script to be INSERTED.

Run SQLite3, Open a New Database, and Read the Artists Script:

Microsoft Windows [Version 6.3.9600]

(c) 2013 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

C:\Users\John>sqlite3

SQLite version 3.8.7.3 2014-12-05 22:29:24

Enter ".help" for usage hints.

Connected to a transient in-memory database.

Use ".open FILENAME" to reopen on a persistent database.

sqlite> .open txdemo.db

sqlite> .read create-insert-artists.sql

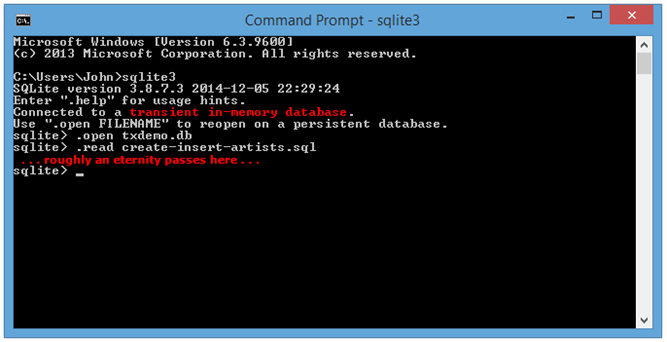

We can see that (depending on your machine - your mileage may vary) executing the script takes roughly 10 seconds. Inserting 275 records should NOT take 10 seconds. Ever.

Console Output from Running Script (Took Way Too Long!):

As mentioned previously, unless we tell it otherwise, SQLite will treat each of those INSERT commands as an individual transaction, which slows things WAAAYYYY DOOOOWWWWN. We can do better. We tell SQLite to override this behavior by explicitly specifying our own transaction, beginning before the INSERT batch, and committing after each INSERT batch.

When we are executing batches of INSERTs, UPDATEs, or DELETEs in a script, wrap all the writes against each table up in a transaction using the BEGIN and COMMIT SQLite Keywords. Modify the create-insert-artists.sql script in out text file by adding a BEGIN before the table INSERTs, and a COMMIT after the table inserts (for scripts involving more than one table, do this for the INSERTs for each table):

Modified Script Wraps INSERTs in single transaction:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS [Artist];

CREATE TABLE [Artist]

(

[ArtistId] INTEGER NOT NULL,

[Name] NVARCHAR(120),

CONSTRAINT [PK_Artist] PRIMARY KEY ([ArtistId])

);

BEGIN;

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (1, 'AC/DC');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (2, 'Accept');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (3, 'Aerosmith');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (4, 'Alanis Morissette');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (273, 'C. Monteverdi, Nigel Rogers');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (274, 'Nash Ensemble');

INSERT INTO [Artist] ([ArtistId], [Name]) VALUES (275, 'Philip Glass Ensemble');

COMMIT;

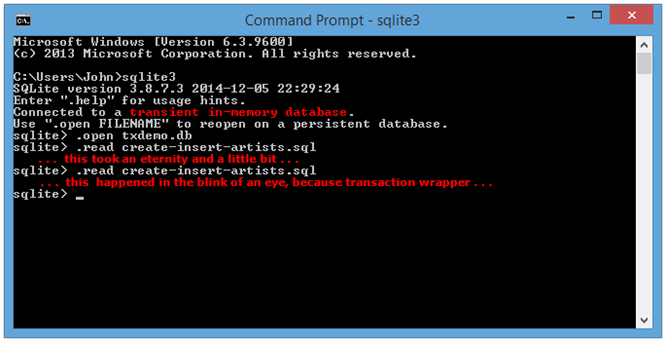

If we re-run our script now, we see a significant performance boost. In fact, the script execution is nearly immediate.

Re-Run the Script in the SQLite Console (this time, with a Transaction):

The above will apply to all INSERTs, UPDATEs, and DELETEs when you execute scripts in the SQLite console.

We see a similar problem when we use SQLite in a .NET application, and the solution is conceptually the same, although the implementation is necessarily a little different. If you are new to using SQLite (and many .NET developers are, at some point), this is exactly the type of confounding quirk that can have you running back to yet another "integrated" Microsoft database solution before giving this great database a chance. "I tried SQLite, but the inserts and updates were too damn slow . . ."

Consider the following Console application example. It is a small, simplistic example, and has no exception handling, but you get the idea. The Main() method performs some basic set-up, then builds a List<User> which is passed to the AddUsers() method.

Program to Insert a List of Users Using System.Data.SQLite:

class Program

{

static string _connectionString;

static void Main(string[] args)

{

string dbDirectory = Environment.CurrentDirectory;

string dbName = "test.db";

string dbPath = Path.Combine(dbDirectory, dbName);

_connectionString = string.Format("Data Source = {0}", dbPath);

CreateDbIfNotExists(dbPath);

CreateUsersTable();

int qtyToAdd = 100;

var usersToAdd = new List<User>();

for(int i = 0; i < qtyToAdd; i++)

{

usersToAdd.Add(new User { Name = "User #" + i });

}

var sw = new System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch(); ;

sw.Start();

int qtyAdded = AddUsers(usersToAdd);

sw.Stop();

Console.WriteLine("Added {0} Users successfully in {1} ms",

qtyAdded, sw.ElapsedMilliseconds);

var allUsers = ReadUsers();

Console.WriteLine("Read {0} Users from SQLite", allUsers.Count());

Console.Read();

}

static void CreateDbIfNotExists(string dbPath)

{

string directory = Path.GetDirectoryName(dbPath);

if (!File.Exists(dbPath))

{

Directory.CreateDirectory(directory);

SQLiteConnection.CreateFile(dbPath);

}

}

static SQLiteConnection CreateConnection()

{

return new SQLiteConnection(_connectionString);

}

static void CreateUsersTable()

{

string sqlTestTable =

@"CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS Users

(

Id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

Name TEXT NOT NULL

)";

using (var cn = new SQLiteConnection(_connectionString))

{

using (var cmd = new SQLiteCommand(sqlTestTable, cn))

{

cn.Open();

cmd.ExecuteNonQuery();

cn.Close();

}

}

}

class User

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}

static int AddUsers(IEnumerable<User> users)

{

var results = new List<int>();

string sqlInsertUsers =

@"INSERT INTO Users (Name) VALUES (@0);";

using (var cn = new SQLiteConnection(_connectionString))

{

cn.Open();

using (var cmd = cn.CreateCommand())

{

cmd.CommandText = sqlInsertUsers;

cmd.Parameters.AddWithValue("@0", "UserName");

foreach (var user in users)

{

cmd.Parameters["@0"].Value = user.Name;

results.Add(cmd.ExecuteNonQuery());

}

}

}

return results.Sum();

}

}

12/17/2014 NOTE: CP User FZelle correctly pointed out that the original code above, and in the next example which follows, was not re-using the SQLiteCommand. The code here has been updated to do this correctly. Also, the call to Close() was redundant, as the SQLiteConnection was wrapped in a using block.

The AddUsers() method creates a connection and a command, opens the connection, and then iterates over the IEnumerable<User>, successively inserting the user data for each into the SQLite database. We are using a System.Diagnostics.Stopwatch to time the execution of the call to AddUsers() from Main().

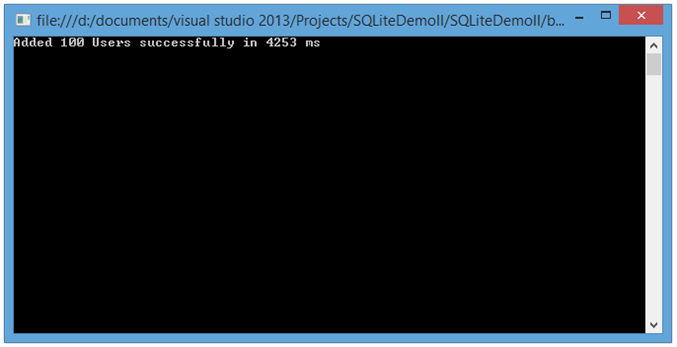

It looks like we've done everything right here - we set up the connection only once, open it only once (opening and closing connections for each loop iteration causes its own performance hit). However, it still takes upwards of four seconds to insert only 100 users. We can see the results in our console output.

Console Output from Example Program Inserting 100 Users:

Pretty lame, but not surprising, given what we have learned about transactionality defaults in SQLite. but, once again, we can do better.

Similar to using the SQLite console, the solution here is also to use a transaction. We can modify the code in the AddUsers() method as follows:

Modified Code for AddUsers() Method Wrapping Command Execution in a Transaction:

static int AddUsers(IEnumerable<User> users)

{

var results = new List<int>();

string sqlInsertUsers = @"INSERT INTO [Users] ([Name]) VALUES (@Name);";

using (var cn = new SQLiteConnection(_connectionString))

{

cn.Open();

using(var transaction = cn.BeginTransaction())

{

using (var cmd = cn.CreateCommand())

{

cmd.CommandText = sqlInsertUsers;

cmd.Parameters.AddWithValue("@Name", "UserName");

foreach (var user in users)

{

cmd.Parameters["@Name"] = user.Name;

results.Add(cmd.ExecuteNonQuery());

}

}

transaction.Commit();

}

}

return results.Sum();

}

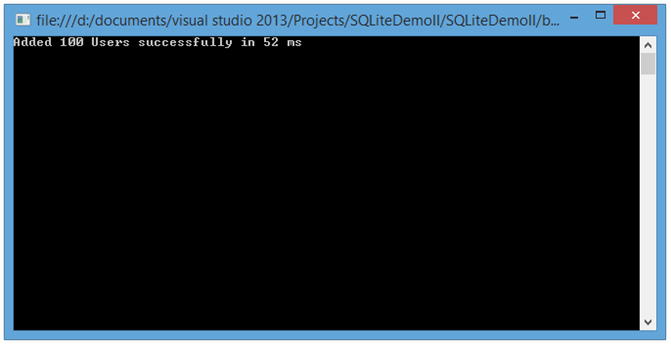

With that, if we run our application again, we see an order of magnitude performance improvement:

Improved SQLite Insert Performance Using Transaction in .NET:

Yep. 52 milliseconds, down from over 4,000 milliseconds.

We've seen how we can realize some serious performance wins in SQLite by using transactions to wrap up bulk operations. However, let's not put the cart before the horse without thinking it through. Sometimes, you actually need a more granular level of transaction to ensure data integrity.

It simply would not do to maximize performance of a banking application if transactions were implemented only at the top level of a batch operation. After all, transactions in the world of relational databases are first and foremost about creating assurance that an operation succeed in its entirety, or not at all.

John on Google CodeProject