In this post, you will learn to create and use commands according to the MVVM pattern, i.e., maintaining separated business logic from graphical context and controls.

Scope

In this article, we'll show a basic ICommand interface implementation, to manage - in accordance with the MVVM pattern - the definition of UI-independent commands, realizing the typical View and Model separation, established by the pattern itself.

Introduction

As we have stated in a previous article (see Basic Outlines and Examples ON MVVM pattern), the MVVM fundamental paradigm is to maintain separated an application graphical part (typically, the part which presents data) from its business logic, or the modus, the code, through which the data are found, initialized, and exposed. In the article linked above, we saw how to obtain that in relation at an object's properties, introducing ad intermediate layer (the so-called ViewModel), which is responsible for making data available (Model's properties) to the View (the UI). We'll see here the same thing about command, or how we can overcome the event-driven logic (let's say, of a button, for example) to move toward a complete separation between the user clickable object, and the code that will be actually executed.

To this end, it will be appropriate to prepare a suitable environment, i.e., a class, containing the data to be presented, an intermediate class for their presentation, and a view, which will be a WPF view in this case too.

A Basic Data Class

As we've done in past examples, we'll start writing a simple class for our core data. In this case, the example will be very simple, designing an element which exposes two properties: a text, identified by a property named Text, and a background, with a consistent property too. Beginning to hypothesize how to use a class like that, we could anticipate a binding to a TextBox, more precisely mutually connecting their Text properties for the content, and Background for the background's color.

Public Class ItemData

Dim _text As String

Dim _backg As Brush = Nothing

Public Property Text As String

Get

Return _text

End Get

Set(value As String)

_text = value

End Set

End Property

Public Property Background As Brush

Get

Return _backg

End Get

Set(value As Brush)

_backg = value

End Set

End Property

Public Sub New()

_text = "RANDOM TEXT"

_backg = New SolidColorBrush(Colors.Green)

End Sub

End Class

In its constructor, that class simply initializes its properties with the values of "RANDOM TEXT" for the Text property, and a green SolidColorBrush as Background. Looking forward its use, we know it will be appropriate - as said in the previous article - to set our View's DataContext. We must create a class which will work as a ViewModel, so that - given an ItemData - it will expose its fundamental properties (or, at least, those properties we really want to use in an operational area).

The ViewModel, First Version

Let's start with a very small ViewModel, small enough for a DataContext initialization. Let's see a class apt to that mean, with functionality as a new ItemData creation, and the exposure - through properties - of the ItemData's properties. The fundamental core of any ViewModel is - as we saw - the INotifyPropertyChanged interface implementation, to trace properties modification, realizing an effective data binding.

Imports System.ComponentModel

Public Class ItemDataViewModel

Implements INotifyPropertyChanged

Dim _item As New ItemData

Public Property Text As String

Get

Return _item.Text

End Get

Set(value As String)

_item.Text = value

NotifyPropertyChanged()

End Set

End Property

Public Property Background As Brush

Get

Return _item.Background

End Get

Set(value As Brush)

_item.Background = value

NotifyPropertyChanged("Background")

End Set

End Property

Public Event PropertyChanged As PropertyChangedEventHandler _

Implements INotifyPropertyChanged.PropertyChanged

Private Sub NotifyPropertyChanged(Optional propertyName As String = "")

RaiseEvent PropertyChanged(Me, New PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName))

End Sub

End Class

In that class, we see the first step is made by creating a new instance of ItemData: calling its constructor, its base properties will be initialized, as we saw above. We'll create then the properties apt to expose "sub-properties", i.e. our data source properties. In this case, I've maintained for ViewModel's properties the same name they possess in the base class. Through them, using Get/Set, the real data modification will take place..

The View, First Version

Last, a basic View: as said, we'll make our ViewModel our Window's DataContext. We'll put on the Window a TextBox, binding it to the properties exposed by the ViewModel. We could write a thing like that:

<Window x:Class="MainWindow"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation

[This link is external to TechNet Wiki. It will open in a new window.] "

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml

[This link is external to TechNet Wiki. It will open in a new window.] "

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:WpfApplication1"

Title="MainWindow" Height="350" Width="525">

<Window.DataContext>

<local:ItemDataViewModel/>

</Window.DataContext>

<Grid>

<TextBox HorizontalAlignment="Left" Height="25" Margin="30,53,0,0"

Text="{Binding Text}" Background="{Binding Background}"

VerticalAlignment="Top" Width="199"/>

</Grid>

</Window>

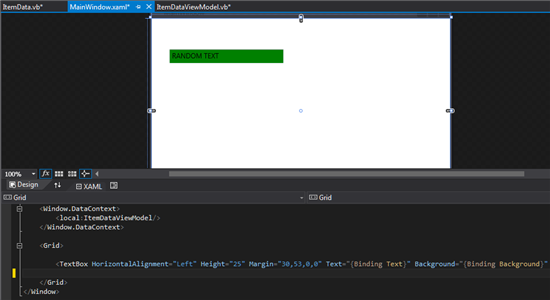

Please note the local namespace declaration, referencing the application itself: without it, we won't be able to reference our ItemDataViewModel class as Window.DataContext, because it is defined in our project. Next, we set our TextBox bindings, on Text and Background properties. Source properties are, obviously, originated in our ViewModel. At this point, we have all we need to produce a first result. Even without executing our code, we'll see how the IDE shows us a Window modified as we expect, thanks to the binding effect. Namely, a TextBox which contains the "RANDOM TEXT" text, on a green background.

We now have a useful base to start speaking about commands.

ICommand Interface

The general scope of a command is to keep separated the semantics of code from the object which will use it. On the one hand, then, we'll have a graphical representation of the command (i.e., a Button, for example), while in our ViewModel will host the real instruction set to be executed - when the developer's imposed conditions are met - when the user sends an input to the graphical command. In our example, we'll enrich our ViewModel with some sub-classes, to expose commands for bind them to the View. Nothing prevents though - if one prefers to do so - the creation of dedicated classes, referencing them in the view model.

The ICommand implementation resides on four fundamental elements: a constructor, CanExecute() and Execute() functions, and the management of CanExecuteChanged event. Its most basilar example could be expressed as follows:

Public Class Command

Implements ICommand

Private _action As Action

Sub New(action As action)

_action = action

End Sub

Public Function CanExecute(parameter As Object) As Boolean Implements ICommand.CanExecute

Return True

End Function

Public Event CanExecuteChanged(sender As Object, e As EventArgs) _

Implements ICommand.CanExecuteChanged

Public Sub Execute(parameter As Object) Implements ICommand.Execute

_action()

End Sub

End Class

We've defined a class named Command, implementing ICommand with its core elements. Action variables represent encapsulations of methods (Delegates). In other words, when we'll call our Command's constructor, we must tell it which sub or function it must invoke. To that end, we'll pass to it a reference to the desired Delegate. That reference will be executed on Execute() method's calling. The CanExecute() method is useful to define when our command will be available to be executed. In our example, we'll always return True, as we want simply to have it always available.

Defined a basic implementation, we could integrate it to our ViewModel: in our example, we suppose we want to introduce a command through which we'll switch our element's background to red. On our View, this function will be delegated to a button's click. We could modify our ViewModel as follows:

Imports System.ComponentModel

Public Class ItemDataViewModel

Implements INotifyPropertyChanged

Dim _item As New ItemData

Public Property Text As String

Get

Return _item.Text

End Get

Set(value As String)

_item.Text = value

NotifyPropertyChanged()

End Set

End Property

Public Property Background As Brush

Get

Return _item.Background

End Get

Set(value As Brush)

_item.Background = value

NotifyPropertyChanged("Background")

End Set

End Property

Public Event PropertyChanged As PropertyChangedEventHandler _

Implements INotifyPropertyChanged.PropertyChanged

Private Sub NotifyPropertyChanged(Optional propertyName As String = "")

RaiseEvent PropertyChanged(Me, New PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName))

End Sub

Dim _cmd As New Command(AddressOf MakeMeRed)

Public ReadOnly Property FammiRosso As ICommand

Get

Return _cmd

End Get

End Property

Private Sub MakeMeRed()

Me.Background = New SolidColorBrush(Colors.Red)

End Sub

Public Class Command

Implements ICommand

Private _action As Action

Sub New(action As action)

_action = action

End Sub

Public Function CanExecute(parameter As Object) As Boolean _

Implements ICommand.CanExecute

Return True

End Function

Public Event CanExecuteChanged(sender As Object, e As EventArgs) _

Implements ICommand.CanExecuteChanged

Public Sub Execute(parameter As Object) Implements ICommand.Execute

_action()

End Sub

End Class

End Class

Note how I've inserted the Command class as a subclass (that's not a mandatory procedure, is simply useful for me to present a less dispersive example). ViewModel declares a variable, _cmd, as new Command, passing to it a delegate (AddressOf) for the previous sub MakeMeRed. What this sub does? Simply, as it can be seen, it takes the current object Background property (by which the same underlying ItemData property is exposed), and set it as a red Brush. As a MVVM rule, the command too must be exposed as a property: I've therefore created FammiRosso property, which exposes our Command externally to the ViewModel.

We could proceed with the introduction of our Command on the View. Let's modify our XAML as follows:

<Window x:Class="MainWindow"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation

[This link is external to TechNet Wiki. It will open in a new window.] "

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml

[This link is external to TechNet Wiki. It will open in a new window.] "

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:WpfApplication1"

Title="MainWindow" Height="350" Width="525">

<Window.DataContext>

<local:ItemDataViewModel/>

</Window.DataContext>

<Grid>

<TextBox HorizontalAlignment="Left" Height="25" Margin="30,53,0,0"

Text="{Binding Text}" Background="{Binding Background}"

VerticalAlignment="Top" Width="199"/>

<Button Content="Button" Command="{Binding FammiRosso}"

HorizontalAlignment="Left" Height="29" Margin="30,99,0,0"

VerticalAlignment="Top" Width="199"/>

</Grid>

</Window>

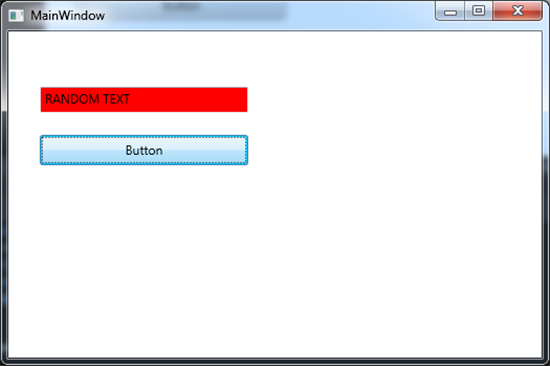

In a Button control, we can bind a command with the property Command. Note how is fast a procedure like that: as our Window's DataContext is on ItemDataViewModel, we could simply write Command="{Binding FammiRosso} to bind the two. If we run our example now, we'll see initially a green background TextBox, caused by ItemData constructor. Clicking our Button will produce a change in the control's background:

It's important to underline, once again, the independence between UI and the underlying logic. With the usual event-driven programming logic, we should have written our code in the Window's code-behind, while, thanks to MVVM, the files which define the UI can be maintained separated from the working logic, avoiding the necessity to modify the two of them in case we must change something in only one of them (unless that change takes place on a fundamental point of contact between the two, say a property name, for example. In this case, though, intervening for an adjustment will be much more easier and fast).

Parametrized Commands

In any scenario, a static command could not be sufficient to satisfy operational requisites. Think about a command which must execute different operation depending on another control's state. There's the need of parametrized command's creation, command which can receive UI's (or any other object's) data, and - on that basis - executing several different tasks.

In our example, we want to implement an additional button. That new button too will change our TextBox's background, but picking it from which the user will write in the TextBox. ItemData's Text property must be passed to our command as a parameter. The basic implementation of a parametrized command is not much different from what we saw above. We could summarize it as:

Public Class ParamCommand

Implements ICommand

Private _action As Action(Of String)

Sub New(action As Action(Of String))

_action = action

End Sub

Public Function CanExecute(parameter As Object) As Boolean Implements ICommand.CanExecute

Return True

End Function

Public Event CanExecuteChanged(sender As Object, _

e As EventArgs) Implements ICommand.CanExecuteChanged

Public Sub Execute(parameter As Object) Implements ICommand.Execute

_action(parameter.ToString)

End Sub

End Class

Please note the only difference from the previous implementation (aside from the class name) resides in the type specification for the Action delegate. We have now an Action(Of String), be it in the variable declaration, and - obviously - in the constructor, and in the execution syntax of Execute() method. Namely, we declare a delegate of any type we wish (my choose of a String will be evident shortly) which will reference a method with the same signature.

Like the previous example, we need the implementation of our Command to be made in our ItemDataViewModel, exposing it through a property. Adding our parametrized command's class to the ViewModel, we'll have:

Imports System.ComponentModel

Public Class ItemDataViewModel

Implements INotifyPropertyChanged

Dim _item As New ItemData

Public Property Text As String

Get

Return _item.Text

End Get

Set(value As String)

_item.Text = value

NotifyPropertyChanged()

End Set

End Property

Public Property Background As Brush

Get

Return _item.Background

End Get

Set(value As Brush)

_item.Background = value

NotifyPropertyChanged("Background")

End Set

End Property

Public Event PropertyChanged As PropertyChangedEventHandler _

Implements INotifyPropertyChanged.PropertyChanged

Private Sub NotifyPropertyChanged(Optional propertyName As String = "")

RaiseEvent PropertyChanged(Me, New PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName))

End Sub

Dim _cmd As New Command(AddressOf MakeMeRed)

Dim _cmdP As New ParamCommand(AddressOf EmitMessage)

Public ReadOnly Property FammiRosso As ICommand

Get

Return _cmd

End Get

End Property

Public ReadOnly Property Message As ICommand

Get

Return _cmdP

End Get

End Property

Private Sub MakeMeRed()

Me.Background = New SolidColorBrush(Colors.Red)

End Sub

Private Sub EmitMessage(message As String)

Try

Me.Background = New SolidColorBrush(CType_

(ColorConverter.ConvertFromString(message), Color))

Catch

MakeMeRed()

End Try

MessageBox.Show(message)

End Sub

Public Class Command

Implements ICommand

Private _action As Action

Sub New(action As action)

_action = action

End Sub

Public Function CanExecute(parameter As Object) _

As Boolean Implements ICommand.CanExecute

Return True

End Function

Public Event CanExecuteChanged(sender As Object, e As EventArgs) _

Implements ICommand.CanExecuteChanged

Public Sub Execute(parameter As Object) Implements ICommand.Execute

_action()

End Sub

End Class

Public Class ParamCommand

Implements ICommand

Private _action As Action(Of String)

Sub New(action As Action(Of String))

_action = action

End Sub

Public Function CanExecute(parameter As Object) As Boolean _

Implements ICommand.CanExecute

Return True

End Function

Public Event CanExecuteChanged(sender As Object, e As EventArgs) _

Implements ICommand.CanExecuteChanged

Public Sub Execute(parameter As Object) Implements ICommand.Execute

_action(parameter.ToString)

End Sub

End Class

End Class

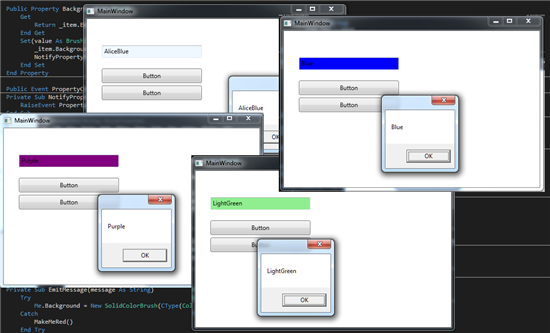

Please note ParamCommand declaration, the declaration of _cmd variable, and the reference to EmitMessage delegate, a subroutine which receives an argument of String type. That routine will try to convert the argument in a color, to make a brush from it and assigning it to the ItemData's Background property. At the same time, it will pop-up a MessageBox, containing the passed String argument. We'll expose our Command through the Message property. Now it must be clear that the argument to be passed to the routine must be - to meet the ends we have thought - the exposed Text property, making it to be typed by the user, received from the parametrized command, and used in the delegate routine's context.

To realize a bind like that, we implement a new Button on our View. It's final XAML will become:

<Window x:Class="MainWindow"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation

[This link is external to TechNet Wiki. It will open in a new window.] "

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml

[This link is external to TechNet Wiki. It will open in a new window.] "

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:WpfApplication1"

Title="MainWindow" Height="350" Width="525">

<Window.DataContext>

<local:ItemDataViewModel/>

</Window.DataContext>

<Grid>

<TextBox HorizontalAlignment="Left" Height="25" Margin="30,53,0,0"

Text="{Binding Text}" Background="{Binding Background}"

VerticalAlignment="Top" Width="199"/>

<Button Content="Button" Command="{Binding FammiRosso}"

HorizontalAlignment="Left" Height="29" Margin="30,99,0,0"

VerticalAlignment="Top" Width="199"/>

<Button Content="Button" Command="{Binding Message}"

CommandParameter="{Binding Text}" HorizontalAlignment="Left"

Margin="30,133,0,0" VerticalAlignment="Top" Width="199" Height="29"/>

</Grid>

</Window>

Note that, as previously, the command-exposing property binding on the Button's Command property. To pass our argument, it will be sufficient to set the CommandParameter property on the Button, with a reference at the property to link/bind. In our case, CommandParameter="{Binding Text}" specifies that the argument to be passed to our command must be found in the binded property Text.

Running our code again, we could type various string in our TextBox (from the System.Windows.Media.Colors class, namely Red, Black, Green, etc.), clicking each time our button and seeing how TextBox's Background property will be modified (and the MessageBox pop-up, too). In case the user types an invalid input, as we can see in EmitMessage() code, the imposed color will be red.

History

- 10th January, 2015: First release for CodeProject