This is the second in a series of articles about subqueries. In this article, we discuss subqueries in the SELECT statement’s column list. Other articles discuss their uses in other clauses.

Using Subqueries in the Select Statement

When a subquery is placed within the column list, it is used to return single values. In this case, you can think of the subquery as single value expression. The result returned is no different than the expression “2 + 2.” Of course, subqueries can return text as well, but you get the point!

When working with sub queries, the main statement is sometimes called the outer query. Subqueries are enclosed in parenthesis, this make them easier to spot.

Be careful when using subqueries. They can be fun to use, but as you add more to your query, they can start to slow down your query.

Simple Subquery to Calculate Average

Let’s start out with a simple query to show SalesOrderDetail and compare that to the overall average SalesOrderDetail LineTotal. The SELECT statement we’ll use is:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

LineTotal,

(SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail) AS AverageLineTotal

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail;

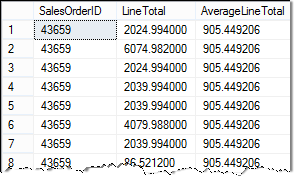

This query returns results as:

The subquery, which is shown in red above, is run first to obtain the average LineTotal.

SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

This result is then plugged back into the column list, and the query continues. There are several things I want to point out:

- Subqueries are enclosed in parenthesis.

- When subqueries are used in a

SELECT statement, they can only return one value. This should make sense, simply selecting a column returns one value for a row, and we need to follow the same pattern. - In general, the subquery is run only once for the entire query, and its result reused. This is because, the query result does not vary for each row returned.

- It is important to use aliases for the column names to improve readability.

Simple Subquery in Expression

As you may expect, the result for a subquery can be used in other expressions. Building on the previous example, let’s use the subquery to determine how much our LineTotal varies from the average.

The variance is simply the LineTotal minus the Average Line total. In the following subquery, I’ve put it in bold. Here is the formula for the variance:

LineTotal - (SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail)

The SELECT statement enclosed in parenthesis is the subquery. Like the earlier example, this query will run once, return a numeric value, which is then subtracted from each LineTotal value.

Here is the query in final form:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

LineTotal,

(SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail) AS AverageLineTotal,

LineTotal - (SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail) AS Variance

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

Here is the result:

When working with subqueries in select statements, I usually build and test the subquery first. SELECT statements can get complicated very quickly. It is best to build them up little by little. By building and testing the various pieces separately, it really helps with debugging.

Correlated Queries

There are ways to incorporate the outer query’s values into the subquery’s clauses. These types of queries are called correlated subqueries, since the results from the subquery are connected, in some form, to values in the outer query. Correlated queries are sometimes called synchronized queries.

If you’re having trouble understanding what correlate means, check out this definition from Google:

Correlate: “have a mutual relationship or connection, in which one thing affects or depends on another.”

A typical use for a correlated subquery is to use one of the outer query’s columns in the inner query’s WHERE clause. This is common since in many cases you want to restrict the inner query to a subset of data.

Correlated Subquery Example

We’ll provide a correlated subquery example by reporting back each SalesOrderDetail LineTotal, and the Average LineTotals for the overall Sales Order.

This request differs significantly from our earlier examples, since the average we’re calculating varies for each sales order.

This is where correlated subqueries come into play. We can use a value from the outer query and incorporate into the filter criteria of the subquery.

Let’s take a look at how we calculate the average line total. To do this, I’ve put together an illustration that shows the SELECT statement with subquery.

To further elaborate on the diagram, the SELECT statement consists of two portions, the outer query and the subquery. The outer query is used to retrieve all SalesOrderDetail lines. The subquery is used to find and summarize sales order details lines for a specific SalesOrderID.

If I were to verbalize the steps we are going to take, I would summarize them as:

- Get the

SalesOrderID. - Return the Average

LineTotal from All SalesOrderDetail items where the SalesOrderID matches. - Continue on to the next

SalesOrderID in the outer query and repeat steps 1 and 2.

The query you can run in the AdventureWork2012 database is:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

SalesOrderDetailID,

LineTotal,

(SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderID = SOD.SalesOrderID)

AS AverageLineTotal

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail SOD

Here are the results of the query:

There are a couple of items to point out:

- You can see I used column aliases to help make the query results easier to read.

- I also used a table alias, SOD, for the outer query. This makes it possible to use the outer query’s values in the subquery. Otherwise, the query isn’t correlated!

- Using the table aliases make it unambiguous which columns are from each table.

Breaking Down the Correlated Subquery

Let’s now try to break this down using SQL.

To start, let’s assume we’re going to just get our example for SalesOrderDetailID 20. The corresponding SalesOrderID is 43661.

To get the average LineTotal for this item is easy:

SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderID = 43661

This returns the value 2181.765240.

Now that we have the average, we can plug it into our query:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

SalesOrderDetailID,

LineTotal,

2181.765240 AS AverageLineTotal

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderDetailID = 20

Using subqueries, this becomes:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

SalesOrderDetailID,

LineTotal,

(SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderID = 43661) AS AverageLineTotal

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderDetailID = 20

Final query is:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

SalesOrderDetailID,

LineTotal,

(SELECT AVG(LineTotal)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderID = SOD.SalesOrderID) AS AverageLineTotal

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail AS SOD

Correlated Subquery with a Different Table

A Correlated subquery, or for that matter any subquery, can use a different table than the outer query. This can come in handy when you’re working with a “parent” table, such as SalesOrderHeader, and you want to include in result a summary of child rows, such as those from SalesOrderDetail.

Let’s return the OrderDate, TotalDue, and number of sales order detail lines. To do this, we can use the following diagram to gain our bearings:

To do this, we’ll include a correlated subquery in our SELECT statement to return the COUNT of SalesOrderDetail lines. We’ll ensure we are counting the correct SalesOrderDetail item by filtering on the outer query’s SalesOrderID.

Here is the final SELECT statement:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

OrderDate,

TotalDue,

(SELECT COUNT(SalesOrderDetailID)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderID = SO.SalesOrderID) as LineCount

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader SO

The results are:

Some things to notice with this example are:

- The subquery is selecting data from a different table than the outer query.

- I used table and column aliases to make it easier to read the SQL and results.

- Be sure to double check your

where clause! If you forget to include the table name or aliases in the subquery WHERE clause, the query won’t be correlated.

Correlated Subqueries versus Inner Joins

It is important to understand that you can get that same results using either a subquery or join. Though both return the same results, there are advantages and disadvantages to each method!

Consider the last example where we count line items for SalesHeader items.

SELECT SalesOrderID,

OrderDate,

TotalDue,

(SELECT COUNT(SalesOrderDetailID)

FROM Sales.SalesOrderDetail

WHERE SalesOrderID = SO.SalesOrderID) as LineCount

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader SO

This same query can be done using and INNER JOIN along with GROUP BY as:

SELECT SO.SalesOrderID,

OrderDate,

TotalDue,

COUNT(SOD.SalesOrderDetailID) as LineCount

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader SO

INNER JOIN Sales.SalesOrderDetail SOD

ON SOD.SalesOrderID = SO.SalesOrderID

GROUP BY SO.SalesOrderID, OrderDate, TotalDue

Which One is Faster?

You’ll find that many folks will say to avoid subqueries as they are slower. They’ll argue that the correlated subquery has to “execute” once for each row returned in the outer query, whereas the INNER JOIN only has to make one pass through the data.

Myself? I say check out the query plan. I followed my own advice for both of the examples above and found the plans to be the same!

That isn’t to say the plans would change if there was more data, but my point is that you shouldn’t just make assumptions. Most SQL DBMS optimizers are really good at figuring out the best way to execute your query. They’ll take your syntax, such as a subquery, or INNER JOIN, and use them to create an actual execution plan.

Which One is Easier to Read?

Depending upon what you’re comfortable with, you may find the INNER JOIN example easier to read than the correlated query. Personally, in this example, I like the correlated subquery as it seems more direct. It is easier for me to see what is being counted.

In my mind, the INNER JOIN is less direct. First, you have to see that all the sales details rows are being returned and then summarized. You don’t really get this until you read the entire statement.

Which One is Better?

Let me know what you think. I would like to hear whether you would prefer to use the correlated subquery or INNER JOIN example.