Introduction

Last week, someone posted a question about producing a random encryption key, and since I'd done something along those lines before, I figured I'd try to reproduce my past efforts, and post an article about it.

General

The idea is to create a completely random key, encrypt the desired data with it, and then somehow share the key with the consumer so that they can decrypt the data, passing both the key and the data to the consumer. This article provides the code to create the key, and leaves the actual encryption stuff and data transfer to the imagination of the programmer.

Creating the Key

I started off with an array of strings. More specifically, an array of guids converted to strings. For the purpose of example, the size of the array was kept to a sane size, but the nature of the code is such that you could easily expand the array to make it even more "interesting" for people wanting to reverse engineer what the code does. The only restriction is that each array element be exactly the same size (in this example, the strings are all 32 characters long).

protected string[] m_markers = new string[11] {"E388e564Bb4040E78fB6268120b5521D",

"84525762d2Ef46178BbEe9CA60cFaBa7",

"245Aa8A0cDe44342A9F0f3E598fD41cA",

"dCc0A41302c345F59698d5CaE32a4AcE",

"08C134fE645847108f5A09a4B7310c10",

"071dBf900Ec1413FaA8bC42f153E1648",

"6A189FdAeD894DaB93590a413CdA1fB6",

"28aCe9C59cE04925815cCfBeA9eC4b04",

"E83a43D7d48E40e5B6b20Df8B72b2708",

"25277a837B554306847dAfDc285E455b",

"2A06dF9f35E04F54a783D4bE6cF00d0B",

};

I also setup some properties to allow the programmer to exercise some control over the creation of the key:

public int KeyMinLength

{

get { return m_keyMinLength; }

set { m_keyMinLength = value; }

}

public int KeyMaxLength

{

get { return m_keyMaxLength; }

set { m_keyMaxLength = value; }

}

public Directions Direction

{

get { return m_direction; }

set { m_direction = value; }

}

public int ActualKeyLength

{

get { return m_keyActualLength; }

set { m_keyActualLength = value; }

}

public int StaticDescriptorLength

{

get { return m_staticDescriptorLength; }

set { m_staticDescriptorLength = value; }

}

The most interesting of these is the Direction property. It represents a set of flags that dictate directions and orientation regarding to traverse the marker array while constructing the key. The following directions can be specified:

Of course, it wouldn't make sense to go both left and right, or up and down, so the class takes reasonable precautions to prevent invalid directions from being specified by calling the ReasonableDirection method before actually trying to build the key. It merely performs a sanity check to make sure the programmer didn't do something strange, like specifying both left and right on a horizontal orietation.

public bool ReasonableDirection()

{

bool reasonable = true;

int orientations = 0;

int horizontals = 0;

int verticals = 0;

orientations += HasDirection(Directions.Horizontal) ? 1 : 0;

orientations += HasDirection(Directions.Vertical) ? 1 : 0;

orientations += HasDirection(Directions.Diagonal) ? 1 : 0;

reasonable = (orientations == 1);

if (reasonable)

{

horizontals += HasDirection(Directions.Left) ? 1 : 0;

horizontals += HasDirection(Directions.Right) ? 1 : 0;

verticals += HasDirection(Directions.Up) ? 1 : 0;

verticals += HasDirection(Directions.Down) ? 1 : 0;

if (HasDirection(Directions.Horizontal))

{

reasonable = (horizontals == 1);

}

else if (HasDirection(Directions.Vertical))

{

reasonable = (verticals == 1);

}

else

{

reasonable = (horizontals == 1 && verticals == 1);

}

}

return reasonable;

}

The image above illustrates some of the possibilities made possible by the Direction property.

- The cyan line indicates two possible Directions -

Right|Down|Diagonal (starting at row 0, column 1), or Left|Up|Diagonal (starting at position row 7, column 8).

- The red line indicates two possible Directions -

Right|Horizontal (starting at row 5, column 12), or Left|Horizontal (starting at position row 5, column 20).

- The green line indicates two possible Directions -

Up|Vertical (starting at row 3, column 24), or Down|Vertical (starting at position row 7, column 24). Notice that this will cause the code to wrap to the far edge.

- The yellow line indicates one possible Direction -

Right|Horizontal (starting at row 9, column 28). Notice also that the code will not only wrap, but will move to the next row. This indicates that the Direction property also includes the RowIncrement flag. This flag is only reasonable for a Horizontal direction, and causes the code to wrap to the next lowest row in the array (regardless of the specified horizontal direction.

Keep in mind that if you allow the class to randomly select a direction, it's entirely possible to end up with a key where all of the characters are the same. This would happen if the Direction ended up being Diagonal with a starting position at one of the corners of the array. If this bothers you, you can always change the random position selection code to ommit the extreme corners. Personally I see nothing wrong with this happening once in a while because each data item could be sent with a different encryption key.

Finally, we arrive at the ConstructKey method. This method uses the Direction property to determine how to traverse the markers array. This is controlled by using adjusters that control how to index into the array, and into an item in the array. First, we run our reasonableness check. If there's a problem, we throw an exception:

private void ConstructKey()

{

if (!ReasonableDirection())

{

throw new Exception("The specified Direction value indicates either both left and right, or both up and down.");

}

Next, we set up our indexing adjusters:

int rowAdjuster = 0;

int colAdjuster = 1;

bool wrapToNextRow = false;

if (HasDirection(Directions.Horizontal))

{

colAdjuster = HasDirection(Directions.Left) ? -1 : 1;

wrapToNextRow = HasDirection(Directions.RowIncrement);

}

else if (HasDirection(Directions.Vertical))

{

rowAdjuster = HasDirection(Directions.Up) ? -1 : 1;

colAdjuster = 0;

}

else

{

rowAdjuster = HasDirection(Directions.Up) ? -1 : 1;

colAdjuster = HasDirection(Directions.Left) ? -1 : 1;

}

Then, to ease typing, we determine where we wrap, and where we wrap to. I use the term "pivot", simply because I like the word "pivot":

int rowPivotAt = (rowAdjuster == -1) ? 0 : m_markers.Length - 1;

int rowPivotTo = (rowAdjuster == -1) ? m_markers.Length - 1 : 0;

int colPivotAt = (colAdjuster == -1) ? 0 : m_markers[0].Length - 1;

int colPivotTo = (colAdjuster == -1) ? m_markers[0].Length - 1 : 0;

int currRow = ArrayIndex;

int currCol = MarkerIndex;

Finally, we get around to actually traversing the array. Because we setup all of our control variables above, the loop is clean, tight, and easy to read:

StringBuilder key = new StringBuilder("");

for (int keyCount = 0; keyCount < ActualKeyLength; keyCount++)

{

key.Append(m_markers[currRow][currCol]);

currCol = (currCol == colPivotAt) ? colPivotTo : currCol + colAdjuster;

currRow = (currRow == rowPivotAt) ? rowPivotTo : currRow + rowAdjuster;

if (wrapToNextRow && currCol == colPivotTo)

{

currRow++;

currRow = (currRow == rowPivotAt) ? rowPivotTo : currRow;

}

}

Key = key.ToString();

}

The Descriptor

By now, you're probably thinking, "Okay, great! We have a randomized key. Now what?"

Anybody that knows anything about transmitting secure info knows you don't just go transmitting this stuff in the clear. The way I see it is that it's perfectly viable to "describe" what you're sending without giving away the whole shebang. Enter "the descriptor".

Remember all of those nifty control variables that were used to actually build our random key? Well, all you have to do is provide that information to a client application that references the same assembly that was used to build the key, and it can decode the key based on those values.

So, let's say our key ended up being 14 characters long, and the starting markers array index was 5, the marker index (where we indexed into the marker in array element 5) was 28, and our Direction was Diagonal | Up | Left. We simply call the GetKeyDescriptor method to build our descriptor string:

public string GetKeyDescriptor()

{

StringBuilder descriptor = new StringBuilder();

descriptor.AppendFormat("{0},", ActualKeyLength);

descriptor.AppendFormat("{0},", ArrayIndex);

descriptor.AppendFormat("{0},", MarkerIndex);

descriptor.AppendFormat("{0},", (int)Direction);

descriptor.Append(MakePadding(descriptor.Length));

KeyDescriptor = descriptor.ToString();

return KeyDescriptor;

}

You may have noticed the last call to Append. This serves two purposes - a) to act as a way to verify the payload of the descriptor string, and to drive hackers absolutely batty trying to figure out what that largish block of bytes means. Here's the method:

private string MakePadding(int currLength)

{

int maxLength = StaticDescriptorLength - currLength;

if (maxLength <= 0)

{

throw new Exception("Descriptor string is already longer than the value indicated by the static descriptor length.");

}

StringBuilder padding = new StringBuilder("");

while (padding.Length < maxLength)

{

padding.Append(Guid.NewGuid().ToString("N"));

}

return (padding.ToString().Substring(0, maxLength));

}

The object of this method is to create enough random padding characters to fill the string to the specified length. As you can see, it simply creates new guids and appends them to the padding string until it exceeds the necessary length, and then calls the Substring method to cut off everything we don't need.

Finally, the client application receiving the descriptor string needs a way to recreate the key on its end. We do that by overloading the BuildKey method with a version that accepts the descriptor string, and parses that string:

public void BuildKey(string descriptor)

{

Key = "";

KeyDescriptor = descriptor;

ActualKeyLength = 0;

ArrayIndex = -1;

MarkerIndex = -1;

Direction = Directions.None;

if (descriptor.Length == StaticDescriptorLength)

{

string[] parts = descriptor.Split(',');

int temp;

if (Int32.TryParse(parts[0], out temp))

{

ActualKeyLength = temp;

}

if (Int32.TryParse(parts[1], out temp))

{

ArrayIndex = temp;

}

if (Int32.TryParse(parts[2], out temp))

{

MarkerIndex = temp;

}

if (Int32.TryParse(parts[3], out temp))

{

Direction = (Directions)(temp);

}

if (ActualKeyLength > 0 && ArrayIndex >= 0 && MarkerIndex >= 0 && Direction != Directions.None)

{

ConstructKey();

}

}

}

If both your web site (or web service) and your client application use this assembly (or one based on it), you can send data with a different encryption key for every descrete block of data, making it so random that breaking the encryption would become virtually impossible. To further shake up the hackers, you could publish a new assembly containing a completely different set of marker strings every 30 days or so. Coupled with click-once deployemnt of the client-side application, things would stay in sync without you having to bend over backwards.

The Sample Application

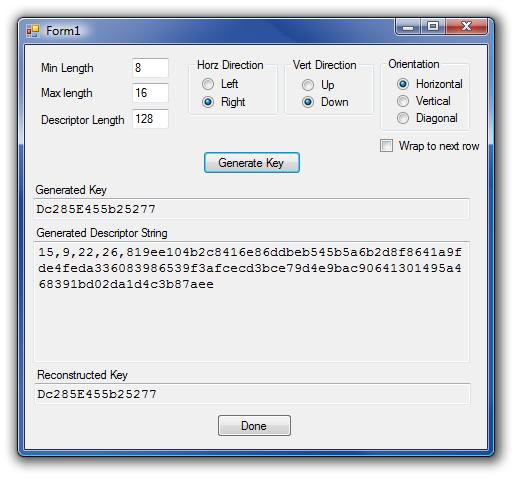

The sample app merely allows you to specify some criteria, and then generate a random key (along with the descriptor string). The last control in the form shows the key rebuilt from the information in the descriptor key (just to prove it works).

In Closing

This code is merely one part of a larger suite of code that would allow secure data transmission without sacrificing data integrity, and should be combined with other measures such as application identifiers, assembly obfuscation and signing, and other techniques. With the descriptor string, you could even specify what encryption algorythm to use, and you could even encrypt the descriptor string to add even more security.

When I wrote code for this a few years ago, I simply encrypted the decsriptor string and prepended it to the encrypted data I was sending. The code on the client side knew what to do because it had the same assemblies.

History

- 10/04/2010 - Original version.