Overview of the Annoyance

I've noticed for a while that on Windows XP, when you use Explorer to delete a file or directory that is in use by another process, it takes what seems like an eternity before an error message appears telling you the file can't be deleted. During this time, there is no indication that Explorer even noticed the delete command. No hourglass, no nothing. By the time the message box appears, I've already hit the delete key a few more times in a futile attempt to get Explorer to just do something, already. Either delete the file or tell me you can't...throw me a bone here.

After reading one of Mark Russinovich's excellent blog entries, I decided I would finally try to figure out what's going on with the painfully-slow in-use error message.

About this Article

In this article, I'll discuss how I tracked down the problem using Process Explorer from Sysinternals.com and WinDbg (part of Microsoft's free Debugging Tools for Windows), and wrote a device driver that patches the offending code. It sure would have been easier if Windows were open source, but hopefully, after seeing some of the techniques I outline in this article, you'll see why I like to refer to Windows as "pry-open source".

I've tried to explain most of the concepts in a way that even non-developers with a decent architectural view of Windows can (hopefully) understand what's going on.

Some notes before we get started:

The Investigation

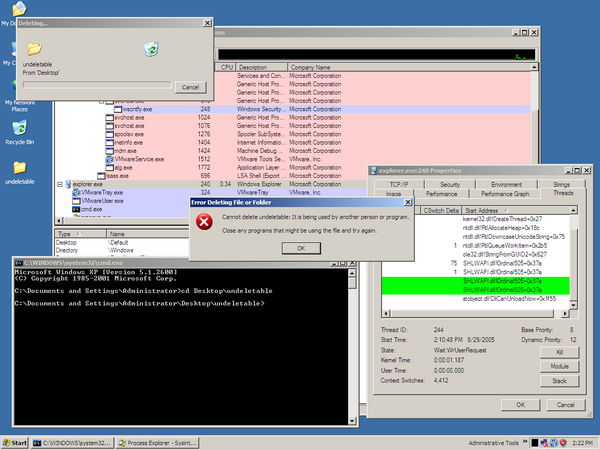

Ironically, the very same behavior I'm complaining about is what makes this an easy problem to investigate. The multi-second delay gives us plenty of time (relatively speaking) to peer into explorer.exe's threads and see what's happening. Let's get set up:

- Fire up Process Explorer.

- Open up the Properties window for your session's explorer.exe process.

- Click on the "Threads" tab and then sort the list by "Start Address". By default, the list is sorted by CPU time, which makes it hard to keep an eye on interesting threads.

Now, to reproduce the annoyance in question:

- Create a new directory. I've named mine "undeletable".

- Launch cmd.exe, and "cd" into the "undeletable" directory. This causes cmd.exe to open a handle to the directory, thereby preventing Explorer (or any other process) from deleting it.

- Click the "undeletable" directory icon in Explorer and hit the Delete key.

While you're waiting for the error message to appear, you should see in the Process Explorer that several threads have been created in the explorer.exe process. Process Explorer kindly highlights them in green:

During the delay before the error message appears, double-click one of the new threads to see its call stack. The call stack is essentially a record of which function the thread is currently executing and which function it will go back to once the current one is done (and which one it will go back to once that one is done, and so on). You should find that one thread's stack looks particularly incriminating:

If you're unfamiliar with viewing call stacks in the Process Explorer, it's important to know that any function you see in the list is currently in the process of calling the function just above it in the list. For instance, if you look at lines 4 and 5 above, you'll see that kernel32.dll!Sleep is currently being called by shell32.dll!_IsDirectoryDeletable.

Even though I don't know exactly what most of the functions in the call stack do, after seeing both "_IsDirectoryDeletable" and "Sleep" in this thread's stack, I was convinced I had found the culprit. One thing I do know is that "Sleep" is a Windows API function that causes a thread to do absolutely nothing for a specified amount of time. My guess was that the function _IsDirectoryDeletable decides to take a little nap after discovering that the directory in question cannot be deleted right away.

Let's test that hunch by watching _IsDirectoryDeletable in action. To do this, fire up WinDbg and attach (using File -> Attach to a Process) to the same explorer.exe process you monitored above using Process Explorer:

After you attach to a process, WinDbg freezes the process (i.e. all of its threads are paused). In order to see the _IsDirectoryDeletable function in action, the first thing we need to do is to set a "breakpoint" on it:

bp shell32!_IsDirectoryDeletable

A breakpoint will cause WinDbg to halt explorer.exe's execution whenever the _IsDirectoryDeletable function in shell32.dll is called. Once the debugger has frozen explorer.exe, you're able to step through the code one instruction at a time and, hopefully, develop some insight into why this function takes so long to execute.

Now that the breakpoint is set, let's un-freeze explorer.exe by typing "g" (you can also choose Debug -> Go).

Now, repeat the "undeletable" experiment again. This time, WinDbg responds immediately, indicating that our breakpoint has been hit:

Breakpoint 0 hit

eax=00000001 ebx=018cf084 ecx=7c80f067 edx=1007001e esi=018cee64 edi=00000104

eip=7ca691a9 esp=018cee14 ebp=018cee30 iopl=0 nv up ei pl zr na po nc

cs=001b ss=0023 ds=0023 es=0023 fs=003b gs=0000 efl=00000246

SHELL32!_IsDirectoryDeletable:

7ca691a9 8bff mov edi,edi

You can safely ignore most of this garbage. The only thing that's important at this point is the fact that explorer.exe is frozen right at the point before it's going to execute the _IsDirectoryDeletable function. This is quite useful because we can now step through the function's instructions one by one. To do this, bring up the Disassembly window (View -> Disassembly). Our breakpoint (and, in this case, the very next instruction to be executed) is highlighted in purple by WinDbg (shown below). The red box was added by me for the purpose of illustrating this article.

Even if you aren't fluent in assembly language, you can learn a lot just by watching the highlighted line move back and forth through the code. Keep hitting F10 (which steps through one instruction at a time) and you'll see what I mean.

You should notice the code looping back on itself several times (five to be exact), each time hitting the line:

call dword ptr [SHELL32!_imp__Sleep]

You should also notice a one-second delay after you hit F10 while on that line. This is most likely the cause of the delay we see in the UI.

Also, each time through the loop, you'll see the call to shell32!IsDirectoryDeletable (a different function, note the missing underscore) being made.

In a nutshell, the code appears to loop five times, each time checking whether the directory can be deleted and, if not, going to sleep for a second. This explains why if, during the delay, you were to close cmd.exe, the "undeletable" directory will disappear shortly after. Since _IsDirectoryDeletable is checking the directory once per second (for a maximum of five seconds), it will whisk it away as soon as it wakes up from its latest one-second nap and sees that it is no longer in use.

Now, we've observed that the loop happens five times, but where is this number coming from? The number 5 appears twice in _IsDirectoryDeletable's code: once at the line I've marked with the red box and another time a few lines after that. The easiest way to figure out which 5 we're looking for is to change one of them and see what happens. My hope was that if I changed one of the 5s to a 0, the loop would happen zero times instead of the usual five. (Sure, it's risky, but why else would reverse-engineering be considered by many to be an extreme sport?)

To modify _IsDirectoryDeletable, copy the address of the instruction to alter (the line with the red box, address 7CA691B4) and open up the Memory window (View -> Memory). Paste the address into the "Virtual" box:

You'll notice that the first three bytes (83 ff 05) match what you see in the second column of the disassembly. If you change the 05 (which I've highlighted in yellow) to 00 and return to the Disassembly window, you'll see that the instruction now reads "cmp edi,0x0" instead of "cmp edi,0x5".

Time to see if our change makes any difference. First, let's disable any breakpoint we set earlier so that we won't break into WinDbg while testing:

bd *

Next, un-freeze explorer.exe by either typing "g" or choosing Debug -> Go. Now, if you repeat the experiment, the "in use" error message should appear immediately. Problem solved!

Some Notes

In the course of my investigation, I determined that there is another function named _IsFileDeletable that is called when deleting a file using Explorer. This function is implemented almost identically to _IsDirectoryDeletable and the method used to both find it and patch it is the same.

Also note that the "patching" shown above is only temporary. It will only affect the one instance of explorer.exe that was modified. If the process is killed and restarted, the changes will be gone. The rest of this article will show a method of making these changes more permanent.

Making it Stick

My first thought when considering how to make my patch permanent was to just open up shell32.dll with a hex editor and modify the two bytes (the "05" in both _IsFileDeletable and _IsDirectoryDeletable). There were two issues with that. Firstly, I wouldn't be able to modify the live %SYSTEMROOT%\system32\shell32.dll because it appears to be loaded by nearly every process running on the system ("Find DLL" in Process Explorer revealed this). This most likely means it is "in-use" and we won't be able to modify it. Secondly, even when I modified a copy of the file and replaced it after booting into the Recovery Console, Windows would somehow manage to replace my new version with the original version after I rebooted. I assume this was Windows File Protection in action, but seeing as it was happening during the boot process, I didn't think the cause would be easy to track down. Plus, this method of patching the file directly wouldn't survive a service pack or hot fix installation. What I wanted was a live patch utility that would automatically run every time the system was booted.

Before I explain my solution, I need to talk a little bit about "KnownDLLs". Essentially, Windows maintains a list of DLLs in the registry that are commonly used by most Windows applications (shell32.dll is one of these). During system boot, these DLLs are mapped into memory as "section objects". When a process needs to load one of these special DLLs, the system will use the cached section object instead of creating a new one. We'll be using the object \KnownDlls\shell32.dll as a starting point for applying the patch. (This is probably an over-simplified explanation, but should be sufficient for our purposes. See this for a more thorough treatment.)

After some more thought, I decided I would write a device driver to patch the code at every boot. This made sense to me for several reasons:

- Drivers run in kernel mode. Although I didn't try it, I assumed that from user mode I wouldn't be able to write to a section of memory that was part of what Microsoft considers a critical system component (shell32.dll's mapped section, in this case). Kernel-mode components can ignore (or, at the very least, consciously disable) any memory protection that user-mode programs are forced to obey. Writing a driver is the easiest way to get code into the kernel. (Note: "Driver" is just the common term for modules that are dynamically loaded into the Windows kernel. We're not actually communicating with a particular hardware device the way a network card driver or video card driver would. In fact, on Linux, drivers are generally called "kernel modules," which is a much more appropriate term for what we're discussing here.)

- A driver can be automatically started at boot time by the Service Control Manager (the same facility that starts "regular" Windows Services such as IIS). Drivers and services also support a "stop" command, which can be delivered by running "net stop drivername" from the command-line. This means easy debugging and testing because the driver can be designed to undo the patch when the "stop" command is received.

- The section objects representing the "KnownDLLs" are accessible in the \KnownDlls directory of the kernel's Object Manager namespace (which has nothing to do with the file system's namespace...you won't find a directory on your hard drive named KnownDlls). Unfortunately, the \KnownDlls directory is not accessible via the Windows API. Running in kernel mode will allow us access to the \KnownDlls\shell32.dll section object. (If you're interested, WinObj from Sysinternals is a great utility for exploring the Object Manager's namespace.)

- Finally, I took a "rootkit" writing class at this year's Black Hat Training in Las Vegas. A kernel-mode rootkit is essentially a driver that modifies the kernel in order to change its behavior. Rootkits are usually interested in hiding files, process and registry keys so that an intruder may remain undetectably in control of a system. Even though that's not the goal here, the need to modify some of the protected, inner-workings of the system is the same. Also, my desire to test-drive some of these rootkit-like techniques probably influenced my decision just as much as any real technical factor did.

Details of the Driver

Basically, the driver will find the \KnownDlls\shell32.dll section and, for each address we want to patch, it will map that memory into the kernel-mode area of the virtual address space, "lock" it (to prevent it from being swapped out of physical memory), and update it. The memory will remain mapped and locked until the driver is unloaded, at which point the changes will be reversed and the memory will be unmapped and unlocked.

At 183 lines, the driver isn't the most complicated piece of code out there. One thing to remember is that I'll be presenting the code in a somewhat different order than what you'll see in the source file. This will enable us to follow the driver's logic without being distracted by the fact that the C compiler requires us to declare our variables at the start of the function.

The main entry point, which for a driver must be called DriverEntry, simply wires-up the Unload routine and then calls the patch function. DriverEntry is the function that will be called when the Service Control Manager issues the "start" command:

NTSTATUS DriverEntry(IN PDRIVER_OBJECT pDriverObject,

IN PUNICODE_STRING pRegistryPath)

{

pDriverObject->DriverUnload = OnUnload;

return DoPatch(TRUE);

}

The DoPatch() function is where the real work takes place. If we're applying the patch (versus undoing the patch), the first thing to do is to get a handle to the \KnownDlls\shell32.dll section and make that memory accessible to us by mapping it into the current process' address space. This is not necessary when undoing the patch because we will save the addresses we found during the initial patching phase.

RtlInitUnicodeString(&us, L"\\KnownDlls\\shell32.dll");

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &us, OBJ_KERNEL_HANDLE, NULL, NULL);

status = ZwOpenSection(&hSection, SECTION_MAP_READ | SECTION_MAP_WRITE, &oa);

status = ZwMapViewOfSection(

hSection,

NtCurrentProcess(),

&pSection,

0,

0,

0,

&viewSize,

ViewShare,

0,

PAGE_READWRITE

);

As a result of the ZwMapViewOfSection call, the pSection variable contains the base address of shell32.dll.

The offsets array (shown below) contains the hard-coded addresses in memory to patch relative to shell32.dll's base address. The two extra NULL fields on each line will hold some memory-management-related data that we'll fill in as we go. The last line {0, NULL, NULL} is simply a placeholder to mark the end of the array:

PATCH_INFO offsets[] = {

{ 0xA916F, NULL, NULL },

{ 0xA91B6, NULL, NULL },

{ 0, NULL, NULL }

};

Let's look at how I determined these memory offsets. The first thing to do is to find shell32.dll's base address. Go back to our WinDbg session from earlier and type:

lm m shell32

You should see something similar to this:

start end module name

7c9c0000 7d1d4000 SHELL32 (pdb symbols) c:\websymbols\shell32.pdb\

290E0039FDA7491EAB979ECE585EE06D2\

shell32.pdb

We can see here that shell32's base address is 0x7C9C0000. (The "0x" prefix is simply the C/C++ way of indicating a hexadecimal number.) The two "05" bytes we want to change in memory are located at 0x7CA6916F (for _IsFileDeletable) and 0x7CA691B6 (for _IsDirectoryDeletable). Thus, the offsets into the file for each patch are 0xA916F (0x7CA6916F - 0x7C9C0000) and 0xA91B6 (0x7CA691B6 - 0x7C9C0000), respectively. (Note: if you can't do this hexadecimal math in your head, the Windows Calculator in scientific mode can do it for you.)

Now that we know which addresses to patch, we need to map those addresses into the kernel-mode area of the memory. This will allow us to lock the pages in memory, thus preventing them from being swapped out to disk. In this case the memory we're modifying is "backed" by shell32.dll. If it were to be swapped out, the memory manager would attempt to write the changes back to shell32.dll. This would most likely cause Windows File Protection to swing into action, which is something we want to avoid, since it would most likely undo the changes we're going to make.

First, we create a Memory Descriptor List (MDL) that points to each address we want to modify. Then we use that MDL to map the pages into kernel-mode memory and lock them:

if (isLoading)

{

pWordToChange = (PULONG)(pSection + pCurrentPatchInfo->offset);

pCurrentPatchInfo->pMdl = IoAllocateMdl(pWordToChange,

sizeof(ULONG), FALSE, FALSE, NULL);

if (pCurrentPatchInfo->pMdl == NULL)

{

DbgPrint("Unable to allocate MDL for VA %08X\n", pWordToChange);

retval = STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

__leave;

}

MmProbeAndLockPages(pCurrentPatchInfo->pMdl, KernelMode, IoReadAccess);

pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped =

(PULONG)MmGetSystemAddressForMdlSafe(pCurrentPatchInfo->pMdl,

NormalPagePriority);

if (pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped == NULL)

{

DbgPrint("MmGetSystemAddressForMdlSafe"

" returned NULL for VA %08X\n",

pWordToChange);

retval = STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

__leave;

}

}

Note: we'll only do this MDL building, mapping and locking if we're first loading the driver and applying the patch. We'll store the MDLs and pointers for use when we are undoing the patch. (This is what the extra NULLs are for in the "offsets" array.)

Next, the driver will verify that the memory locations we are going to update actually contain the expected original values. If shell32.dll is ever updated by a service pack or hot fix, I'd hate to just stomp over some unrelated bit of memory that happens to live where _IsFileDeletable and _IsDirectoryDeletable used to be. The patchedBytes and unpatchedBytes constants indicate what we expect to see at these memory addresses both before and after patching:

const ULONG unpatchedBytes = 0xFF2A7D05;

const ULONG patchedBytes = 0xFF2A7D00;

expectedBytes = isLoading ? unpatchedBytes : patchedBytes;

newBytes = isLoading ? patchedBytes : unpatchedBytes;

The following code, which verifies the memory location's current contents, is executed once for each address in memory to be patched:

if (*pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped != expectedBytes)

{

DbgPrint(

"Offset %08X (address %08X) didn't match. "

"Actual value: %08X. Expected: %08X\n",

pCurrentPatchInfo->offset,

pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped,

*pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped,

expectedBytes

);

retval = STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

__leave;

}

Based on the "isLoading" parameter we pass to it, the DoPatch function will change both what it expects to find before patching and what it will write during the patch process. You'll see that DriverEntry calls DoPatch(TRUE) whereas OnUnload calls DoPatch(FALSE). This is how we are able to undo the patch when the driver receives a "stop" command from the Service Control Manager.

All that's left to do now is to actually change the values. The following code is executed once for each of the two addresses we're changing:

*pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped = newBytes;

DbgPrint(

"Offset %08X at VA %08X changed to %08X\n",

pCurrentPatchInfo->offset,

pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped,

*pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped

);

if (!isLoading)

{

MmUnmapLockedPages(pCurrentPatchInfo->pMapped, pCurrentPatchInfo->pMdl);

MmUnlockPages(pCurrentPatchInfo->pMdl);

IoFreeMdl(pCurrentPatchInfo->pMdl);

}

Also note that if we're undoing the patch, we'll release both the locked memory and the MDL for each offset that was patched.

Building the Driver

If you have the DDK installed, you can build the driver yourself. First, bring up the DDK command prompt (mine is under Start -> Programs -> Development Kits -> Windows DDK 3790 -> Build Environments -> Windows Server 2003 -> Windows Server 2003 Free Build Environment). "cd" into the directory where you have the source files, and type:

build -c

That's it! The completed driver (named "NoDeleteDelay.sys") should be located in the "objfre_wnet_x86\i386" directory. Note: there are reportedly some issues with the DDK's build utility when your source files are in a directory that contains spaces in the pathname (e.g. "c:\Documents and Settings\Administrator\My Documents" probably isn't going to work).

Loading and Testing

There are several ways to get the driver loaded into the kernel. The easiest way during testing is to use Greg Hoglund's driver installer utility:

You'll also notice I'm using DbgView from Sysinternals to view the output from the DbgPrint statements in the code.

You can now try the "undeletable" experiment from the beginning of the article and see that the "in use" error message appears instantly. Also, if you click "Stop" in InstDrv and retry the test, you'll once again observe the usual five-second delay.

Another way to get the driver into the kernel on a more permanent basis is to use the Installer.exe utility I've included in the article's archive file. Just copy both Installer.exe and NoDeleteDelay.sys to the directory where you'd like them to live, then run Installer.exe. There's no uninstall functionality built in to Installer.exe, but if you want to remove the driver, just use InstDrv.exe from above. Type in "NoDeleteDelay" as the full pathname to the driver (no, it isn't the full path, but since the driver is already installed, it doesn't matter). Click "Stop", followed by "Remove".

Some Final Thoughts

This is a version 1.0 piece of software. Here are some things I've thought about but haven't spent much time investigating. (An explanation of these problems is beyond the scope of the article and not understanding them shouldn't detract from the usefulness of what's been presented.)

- Although I'm treating them as if they were, the memory locations pointed to by the "offsets" array are not word-aligned. To my knowledge, the x86 is pretty forgiving about alignment issues, but in a production-grade driver we'd probably want to be doing aligned memory accesses.

- There's no flexibility in dealing with older or newer versions of shell32.dll. If a service pack or hot fix does modify the file, the driver will refuse to patch it. I'm sure I could either scan memory to find the offsets or do something more tricky like programmatically consulting a .pdb (symbol) file, but so far, the hard-coded method Works for Me™.

- I'm not sure why the memory manager doesn't try to write the modified pages back to shell32.dll. I suspect that it's because the entries in the Page Frame Number Database representing the physical pages we've modified always have a "reference count" of at least 1 (because they're locked). If my understanding is correct, this means they will not be moved to the "Modified List" and thus will not be written to disk by the Modified Page Writer. If anyone can expand on this, please leave a comment.

- There may be some huge flaw I don't know about in my method of patching this annoyance. Even if this is the case, I hope the article stands as a good introduction to some of the techniques available to you when confronted with this type of a problem.

Recommended Reading

- Rootkits: Subverting the Windows Kernel, Greg Hoglund and James Butler

- Microsoft Windows Internals, 4th Edition, Mark E. Russinovich and David A. Solomon

- Reversing: Secrets of Reverse Engineering, Eldad Eilam

History

- Sep 23, 2005: Initial submission.