Introduction

Description to finite element method is available in numerous books. Free beginner's level codes are easily available in books and on internet. However, programs giving a thorough treatment to the implementation of Finite Element procedures are scarce. Further, finite element programs written entirely in VB.NET are not easily found.

This article attempts to present a thorough framework for performing finite element analysis of 2D plane-stress/plane strain problems. The element selected is simplistic but nevertheless suffices to express the concepts on which a finite element program is built.

Further, finite element system of equations may be efficiently solved by employing the banded nature of the equations. While some books do give codes for banded solvers, they may be either far from being efficient or are written in style that is not very clear. A robust parallel banded solver is also explained here to fill the void.

It is expected that the framework will give a good initial kick-start to a programmer attempting to write his own finite element analysis program.

Background

Finite Element Method is a very well-developed science. No attempts are made here to explain the mathematics behind the procedure. It is recommended that the readers understand the method well before attempting to program it. While some fundamentals shall be explained,

Finite Element Method

Let's quickly refresh the fundamentals of the finite element method. Please remember that programming the finite element method is almost impossible unless you thoroughly understand and appreciate the underlying ideas.

Most physical phenomena can be represented by partial differential equations, often of large orders. But solution of the such differential equations may not be possible or be cumbersome. In such cases (most often), we resort to numerical methods for solution. Finite Element Method is one such numerical method. The finite element method (FEM) represents the partial differential equations as a set of linear algebraic equations. It should be noted that significant accuracy may be lost in converting partial differential equations to a set of linear algebraic equations. Thus, the results of FE analysis have inherent errors. Further, computational procedures also infuse errors in the solutions. Hence, the results of any finite element analysis must be carefully studied before accepting as the correct solution to the problem at hand.

An important part of the finite element solution involves development of the element. An element, at the core, characterizes variation of the solution over the domain. The quality of the solution depends heavily on the quality of the elements uses.

Steps to Finite Element Analysis

In general, the following steps are required to be performed in any finite element analysis.

- Discretize the Continuum

- Generate Element Matrices: Stiffness matrix; load vector

- Assemble Element Matrices: Form global Stiffness matrix

- Apply Boundary Conditions

- Solve Equations and Calculate Deformations

- Calculate Strains

- Calculate Stresses

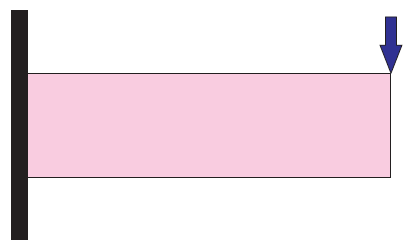

Discretization of the continuum involves dividing the given problem domain into number of subdomains called "elements". Each element is bounded and defined by imaginary points called "nodes". For example, consider a beam as shown in figure below:

To analyse the beam by finite element method, we must subdivide the domain (discretize) it into number of finite elements. The type of element is a matter of choice that the analyst must select based on his engineering experience and judgement. If we were to discretize the domain by quadrilateral elements, it could look like:

An element is defined by nodes. In the domain, each element can be seen separately as:

Discretization or "meshing" as more commonly known, is a huge science in itself and is considered to be out of scope for this article.

Each element assumes a displacement field over the domain. Based on this assumption, the stiffness matrices of the element get generated. A 3-noded triangular element having linear variation of deformations over the domain has been assumed here. The element has linear shape functions having horizontal and vertical translation at each node. The shape function (at node 1) and degrees of freedom at each node may be depicted as:

The element is very basic and simplistic, but suffices to provide for the basic understanding. The element has 2 degrees of freedom per node and hence produces a 6x6 stiffness matrix. Since the deformations are linear, the strains and consequently the stresses are constant. Hence, this element is commonly known as the Constant Strain Triangle (CST). The stiffness matrix may be derived using the minimization of potential energy or Rayleigh-Ritz Method or any other variational method. The readers are requested to refer to more fundamental references on the subject. For completeness, the key equations for deriving the stiffness matrix of the element are presented here.

Each node has two degrees of freedom - u and w, or commonly termed as u and v. Shape functions approximate the variation of a field over the domain of the element. Thus, at any point on the element, the displacements may be obtained as:

$ \begin{aligned} u = \begin{Bmatrix} u \left(x,y \right)\\ v \left(x,y \right) \end{Bmatrix} & = \begin{bmatrix} N_1 & 0 & N_2 & 0 & N_3 & 0\\ 0 & N_1 & 0 & N_2 & 0 & N_3 \end{bmatrix} \\ u_{2x1} & = N_{2x6} \; d_{6x1} \\ u \left(x,y\right) & = N_1 u_1 + N_2 u_2 + N_3 u_3\\ v \left(x,y\right) & = N_1 v_1 + N_2 v_2 + N_3 v_3 \\ N &= \begin{bmatrix} N_1 & 0 & N_2 & 0 & N_3 & 0\\ 0 & N_1 & 0 & N_2 & 0 & N_3 \end{bmatrix}\end{aligned} $

where, [N] is the Shape Function matrix and the shape functions are given by:

$\begin{aligned} N_1 &= \frac{a_1+b_1 x +c_1 y}{2A} \\ N_2 &= \frac{a_2+b_2 x +c_2 y}{2A} \\ N_3 &= \frac{a_3+b_3 x +c_3 y}{2A} \end{aligned} $

where, A is the area of triangular element, which may be determined as half of the determinant of the Jacobian matrix or as:

$\begin{aligned} A = \textbf{area of triangle} = \frac{1}{2} \textbf{det} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_1 & y_1 \\ 1 & x_2 & y_2 \\ 1 & x_3 & y_3 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned} $

Usual procedure of generating the stiffness matrix involves the calculation of the Jacobian Matrix [J], Strain-Displacement linking matrix "[B]" and finally calculating the stiffness matrix [Ke] as:

$\begin{aligned} \left[K_e\right] & = \int_{Vol} B^T D B dv \end{aligned} $

where, as per the usual notations, [B] is the strain-displacement linking matrix and [D] is the constitutive matrix.

If \(x_i\) and \(y_i\) are the coordinates of the node \(i\) of a given element, \(x_{ij}\) is defined as \(x_{ij} = x_i - x_j\). The approximation of strains and subsequent computation of strain-displacement matrix [B] may be carried out as:

$\begin{aligned} \varepsilon &= \begin{Bmatrix} \varepsilon_x\\ \varepsilon_y\\ \gamma_{xy} \end{Bmatrix}= \begin{Bmatrix} \frac{\partial u}{\partial x}\\ \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\\ \frac{\partial u}{\partial y}+ \frac{\partial v}{\partial x} \end{Bmatrix} = B \; d \\ B &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial N_1 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial x} & 0 & \frac{\partial N_2 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial x} & 0 & \frac{\partial N_3 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial x} & 0\\ 0 & \frac{\partial N_1 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial y} & 0 & \frac{\partial N_2 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial y} & 0 & \frac{\partial N_3 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial y} \\ \frac{\partial N_1 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial N_1 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial N_2 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial N_2 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial N_3 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial N_3 \left(x,y\right)}{\partial x} \end{bmatrix} \\ \left[B\right] &= \frac{1}{|J|} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} y_{23} & 0 & y_{31} & 0 & y_{12} & 0 \\ 0 & x_{32} & 0 & x_{13} & 0 & x_{21} \\ x_{32} & y_{23} & x_{13} & y_{31} & x_{21} & y_{12} \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned} $

The constitutive matrix for a 2D membrane problem depends on the assumption of plane stress or plane strain condition. For plane stress condition, the [D] matrix looks like:

$ \left[D\right] = \frac{E}{\left(1-\nu^2\right)} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & \nu & 0 \\ \nu & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{1-\nu}{2} \end{bmatrix}$

For plane strain condition,

$ \left[D\right] = \frac{E}{\left(1+\nu\right) \left(1-2\nu\right)} \begin{bmatrix} 1- \nu & \nu & 0 \\ \nu & 1+\nu & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{1}{2}- \nu \end{bmatrix}$

where, \(E\) is the modulus of elasticity of the material (isotropic) and \(\nu\) is the Poison's ratio. The Jacobian matrix \(\left[J\right]\) is obtained as:

$ \left[J\right] = \begin{bmatrix} x_{13} & y_{13} \\ x_{23} & y_{23} \end{bmatrix}$

The area of the triangle is obtained as \(A = \frac{1}{2} |J|\)

B matrix is in terms of 2D coordinates (x and y). Thus, the product \(B^T D B \) gives the area part of the volume integral. The final equation for stiffness matrix becomes:

$\begin{aligned} \left[K_e\right] & = a \cdot t \cdot \left( B^T D B\right) \\ \end{aligned} $

where, t is the thickness of the element.

The procedure described above for generation of element stiffness matrix can be shown in code as:

Private Function getDetJ() As Double

Return (x13 * y23 - x23 * y13)

End Function

Public Function getB() As Double(,)

Dim B(2, 5) As Double

Dim detJ As Double = getDetJ()

B(0, 0) = y23 / detJ

B(1, 0) = 0.0

B(2, 0) = x32 / detJ

B(0, 1) = 0.0

B(1, 1) = x32 / detJ

B(2, 1) = y23 / detJ

B(0, 2) = y31 / detJ

B(1, 2) = 0.0

B(2, 2) = x13 / detJ

B(0, 3) = 0.0

B(1, 3) = x13 / detJ

B(2, 3) = y31 / detJ

B(0, 4) = y12 / detJ

B(1, 4) = 0.0

B(2, 4) = x21 / detJ

B(0, 5) = 0.0

B(1, 5) = x21 / detJ

B(2, 5) = y12 / detJ

Return B

End Function

Private Function getAe() As Double

Return getDetJ() * 0.5

End Function

Public Function getD() As Double(,)

Dim D(2, 2) As Double

Dim c As Double

If ProblemType = ProblemTypes.PlaneStress Then

c = ElasticityModulus / (1.0 - (PoissonRatio * PoissonRatio))

D(0, 0) = 1.0 * c

D(1, 0) = PoissonRatio * c

D(2, 0) = 0.0

D(0, 1) = PoissonRatio * c

D(1, 1) = 1.0 * c

D(2, 1) = 0.0

D(0, 2) = 0.0

D(1, 2) = 0.0

D(2, 2) = (1 - PoissonRatio) * 0.5 * c

Else

c = ElasticityModulus / ((1 + PoissonRatio) * (1.0 - 2 * PoissonRatio))

D(0, 0) = (1.0 - PoissonRatio) * c

D(1, 0) = PoissonRatio * c

D(2, 0) = 0.0

D(0, 1) = PoissonRatio * c

D(1, 1) = (1 - PoissonRatio) * c

D(2, 1) = 0.0

D(0, 2) = 0.0

D(1, 2) = 0.0

D(2, 2) = (0.5 - PoissonRatio) * c

End If

Return D

End Function

Public Function getKe() As Double(,)

Dim B(,) As Double = getB()

Dim BT(,) As Double = getBT(B)

Dim D(,) As Double = getD()

Dim teAe As Double = Thickness * getAe()

Dim BTD(,) As Double = MultiplyMatrices(BT, D)

Dim Ke(,) As Double = MultiplyMatrices(BTD, B)

Dim i, j As Integer

For i = 0 To 5

For j = 0 To 5

ke(i, j) = ke(i, j) * teAe

Next

Next

Return ke

End Function

Private Function getBT(ByRef B(,) As Double) As Double(,)

Dim BT(5, 2) As Double

Dim i, j As Integer

For i = 0 To 2

For j = 0 To 5

BT(j, i) = B(i, j)

Next

Next

Return BT

End Function

Private Function MultiplyMatrices(ByRef a(,) As Double, ByRef b(,) As Double) As Double(,)

Dim aCols As Integer = a.GetLength(1)

Dim bCols As Integer = b.GetLength(1)

Dim aRows As Integer = a.GetLength(0)

Dim ab(aRows - 1, bCols - 1) As Double

Dim sum As Double

For i As Integer = 0 To aRows - 1

For j As Integer = 0 To bCols - 1

sum = 0.0

For k As Integer = 0 To aCols - 1

sum += a(i, k) * b(k, j)

Next

ab(i, j) += sum

Next

Next

Return ab

End Function

Assembly of Equations

The element equations give the properties of the element, not the body being analysed. To analyse the body, all the finite elements must be joined together. This process is mathematically known as assembly of equations. Each element stiffness matrix is assembled to form a global a global matrix. The element matrix is a square matrix of size (Element DOFs x Element DOFs). The stiffness matrix for entire body is of the size (Total DOFs x Total DOFs). Usually, the total degrees of freedom of an assembled body may be in the order of a few hundreds of thousands. We usually try to mesh the domain in such a way that the total degrees of freedom are as few (thousands) as possible, but it is normal to see the degrees of freedom in order of a million in a complex structure. The memory required for a decent 10,000 DOF structure would then be:

Number of entries in the matrix = \(10,000 \times 10,000 = 10^8\).

Each entry if saved as a double would require 8 bytes. Thus, the total matrix would require 0.8 GB. Manipulating a matrix of this size would be time consuming and inhibitive. For decent size structures, we may get a global stiffness matrix that cannot be accommodated in the system memory. However, stiffness matrices are sparse and contain a lot of zeros. These zeros can be avoided to be worked on. This allows us to use smart schemes for storing the stiffness matrix. Stiffness matrices are usually stored in the following formats:

- Banded Matrix

- Skyline Storage

This framework stores the global stiffness matrix in a banded matrix form. The equation solver also must be appropriately modified to handle the type of storage scheme adopted. A gauss elimination solver which works on banded matrices is implemented and given here. The solver implements parallel processing over the factorization block which makes it fast and robust.

The assembly of elements involves placing each elemental matrix in appropriate position in the global matrix based on the degree of freedom. The procedure may be best understood by considering an example.

Consider the schematic of a cantilever beam as shown in figure below:

A good mesh would be to discretize this beam into a large number of elements. However, for understanding the procedure, we discretize this beam into a coarse mesh as shown below:

The degrees of freedom at each node are tied by the node number. Thus, the degrees of freedom at each node may be given as:

The element stiffness matrices formed for each element will thus be placed in the global stiffness matrix. An example is shown below:

This produces an assembled global stiffness matrix as:

The algorithm depicted here is implemented as:

Private Sub AssembleKg(ByRef Ke(,) As Double, ByRef Kg(,) As Double, ElementNo As Integer)

Dim i, j As Integer

Dim dofs() As Integer = {getDOFx(Elements(ElementNo).Node1 - 1),

getDOFy(Elements(ElementNo).Node1 - 1),

getDOFx(Elements(ElementNo).Node2 - 1),

getDOFy(Elements(ElementNo).Node2 - 1),

getDOFx(Elements(ElementNo).Node3 - 1),

getDOFy(Elements(ElementNo).Node3 - 1)}

Dim dofi, dofj As Integer

For i = 0 To 5

dofi = dofs(i)

For j = 0 To 5

dofj = dofs(j) - dofi

If dofj >= 0 Then

Kg(dofi, dofj) = Kg(dofi, dofj) + Ke(i, j)

End If

Next

Next

End Sub

Private Function getDOFx(NodeNo As Integer) As Integer

Dim nDofsPerNode As Integer = 2

Return (NodeNo) * nDofsPerNode

End Function

Private Function getDOFy(NodeNo As Integer) As Integer

Dim nDofsPerNode As Integer = 2

Return NodeNo * nDofsPerNode + 1

End Function

Private Function getHalfBandWidth() As Integer

Dim i As Integer

Dim n(2) As Integer

Dim MaxDiff As Integer = 0

Dim diff As Integer

For i = 0 To NElements - 1

n(0) = Elements(i).Node1

n(1) = Elements(i).Node2

n(2) = Elements(i).Node3

diff = n.Max - n.Min

If MaxDiff < diff Then MaxDiff = diff

Next

Dim hbw As Integer = (MaxDiff + 1) * 2

If hbw > NNodes * 2 Then hbw = NNodes * 2

Return hbw

End Function

Note that if we swap nodes 1 and 2, the numbering will be more efficient and the resulting band will be more compact. The skyline storage for the matrix shown above would look like:

Skyline storage scheme is obviously more robust, nevertheless, half band storage scheme is adopted here. The dark purple squares show non-zero terms. Thus, avoiding zero terms may allow us to store only the band as shown:

Further, the stiffness matrix for linear problems are symmetric in nature. This allows us to store only a half of the band and still get the correct solution. This calls for a half band storage scheme as adopted in this framework:

The stiffness matrix characterizes the structure / body as if floating in space. The stiffness matrix at this point of time is singular and means that if the structure is given even a slightest disturbance, it will show infinite rigid body deformations. To perform meaningful analysis, we must constrain the body by applying boundary conditions. Boundary conditions could be in the form of loads and supports. While the loads could be of many types, this article considers only nodal forces for example purpose. Further, the supports also could be of many types. Only restraints in x and y direction are considered.

The supports are applied by penalty approach. This involves multiplying the principal diagonal term corresponding with restrained degree of freedom with a large number. Discussion of in-depth mathematics behind the penalty approach is considered to be beyond the scope of this article.

Once the boundary conditions are applied, the next step is solution of equations using gauss elimination and computation of deformations at each degree-of-freedom. This framework performs gauss elimination on banded matrices. After computing the deformations, the elemental deformations can be extracted to compute the strains from the equation \( \{ \epsilon \} = [ B ] \{ d \}\) as explained above. The elemental stresses are then calculated from Hooke's law.

Plotting of the elemental strains or stresses require a color map to be defined. A color map defines a variation of color from minimum value to maximum value. For instance, if stress ranges from -20 to 350, the color map will spread the specified colors between -20 and 350. Once the color spreading is done, the index of the color corresponding to the value required can be easily determined by linear interpolation. Here, the color map is defined to vary between Red - Yellow - Green - Cyan - Blue. The code making color map looks like:

Private Sub setColors()

Dim mainColors() As Color = {Color.Blue, Color.Cyan, Color.LightGreen,

Color.Yellow, Color.Red}

Dim nColors As Integer = mainColors.Length

Dim percentStep As Double = 100 / (nColors - 1)

Dim Indices(nColors - 1) As Integer

Dim i, j As Integer

For i = 0 To nColors - 1

Indices(i) = CInt(i * percentStep / 100 * nSegs)

Next

Indices(0) = 0

Indices(Indices.Length - 1) = nSegs

ReDim Colors(nSegs)

Dim c() As Color

For i = 0 To Indices.Length - 2

c = getSteppedColors(mainColors(i + 1), mainColors(i), Indices(i + 1) - Indices(i))

For j = 0 To c.Length - 1

Colors(Indices(i) + j) = c(j)

Next

Next

End Sub

Once the colors are set in the array, the required color may be retrieved simply by:

Public Function getColor(Value As Double) As Color

Dim rangeVal As Double = Max - Min

Dim dv As Double = Value - Min

Dim ratio = dv / rangeVal

Dim colIndex As Integer = CInt(ratio * nSegs)

Return Colors(colIndex)

End Function

Using the code

The finite element framework is implemented in VB.Net and named btFEM. The main classes implemented are:

- CST - Implementation of the Constant Strain Triangle. The class returns [B], [D] and [Ke].

- btGauss - Parallel and serial implementations of the banded gauss solver for solution of equations \( [K]{d} = {r}\)

- Element - Implementation of element. This is different than CST. Element class contains upper level information such as bounding node numbers for each element, etc.

- Node - Contains definition for the coordinate of each node

- PointLoad - Contains definition for the loads in x and y direction for specified node

- ColorMap - Implements color bar to show stress and strain variation over the body

The start-up file: frmbtFem implements a graphical display of the opened model. Please note that a mesh of the model has to be supplied to this program. Left click zooms in and right click zooms out on the model view. Scroll bars pan the model and a button on right bottom of the screen resets zoom to 1 and pan values to 0. An opened finite element model looks like:

To analyse the structure, click on menu "Model" -> "Analyse". Upon analysis, the program shows the deformed shape as shown below:

Various results may be viewed such as stresses in x direction, stress in y direction and shear stress, or strains in x direction, strains in y direction and shear strains. For example, the plot for stress in x direction is as shown below:

The defformations, stresses and strains may be viewed in a textbox by clicking menu Model -> Results. The framework has been validated by comparing deformations and stresses with standard problems such as cantilever beams with point loads at free end, simply supported beams. The input files for the same have been included with the project files. A typical validation run for a plate with hole is shown in figure below, which shows variation of stress \(\sigma_x\):

Points of Interest

Finite element analysis is a challenging and computationally intense simulation. The core challenge lies in efficient computation of element matrices and solution of equations. Gauss elimination is a versatile technique for solution of equations and can be easily and efficiently modified to work on banded matrices.

Programming the finite element method has been described here. Availability of the complete working program is expected to enhance the understanding of the readers. Robust banded assembler and solver have been included as stand alone classes, which can be easily integrated in any code.

History

Article version 2.