Contents

Introduction

Streaming is mostly referred as a delivery system for media content or dynamic data where it is beneficial to begin processing while data is being delivered. In reality, HTTP was not designed for data streaming. HTTP communications are stateless, and they take place over TCP/IP where there is no continuous connection between the ends. Usually, HTTP responses are buffered rather than streamed. HTTP 1.1 added support for streaming through keep-alive header so data could be streamed, but yet for performance proposes, the majority of implementations including ASP.NET tend to buffer the content, send it, and close the connection. As a result, there are few real world applications that use HTTP for streaming data, and normally, an additional protocol is built on top of HTTP for reconnection and error detection. However, this does not pose a problem because there are other UDP-based protocols that can be used for streaming where it is needed.

So, why would we need data streaming over HTTP? Because, we build our web applications over HTTP. Playing video clips, displaying RSS fields, and updating time sensitive data are considered common features of a webpage nowadays, but yet, we are bounded to HTTP capabilities. Here is where the browsers make use of plug-ins to overcome these boundaries, and also add new troubles!

Plug-ins are executed outside of your application’s context. Unlike Hyper Text Markup Language or JavaScript, plug-ins are mainly compiled binaries and they are difficult to customize. This is not to mention security, accessibility, platform independency, and web standards issues that are involved in pages that use plug-ins. While using plug-ins seems to be inevitable for pages with rich contents, AJAX has created high hopes in my opinion. Even though JavaScript language, as the version of today (the latest 1.7 in Firefox 2), is not fully capable of performing the tasks associated with plug-ins, I believe the future versions can offer enough browser integration and supporting libraries which eliminate the need of using complied plug-ins. I know this sounds very abstract, that is why I decided to write an AJAX application that does the most common task associated with plug-ins: video player. This AJAX video player is a scripted prototype-based video player that runs in JavaScript enabled HTML browsers that support Base64 encoded images (almost all modern browsers but IE). The AJAX video player can broadcast live (using an XML service) or cached video streams (XML file) to a variety of users on different platforms and browsers.

Live sample: Watch the Snoopi at pumpkin patch from AJAX Video Player!

Using the code

Background

A video is a sequence of framed images that are displayed at a rate one after another. If we had all frames of a video clip in our browser, we could display them one after another at a frame rate and there we had our video playing! This sounds like a plan, let us see how we can translate this into an actual web application. From what we planned, we divide our efforts into smaller steps:

Step 1: Getting the frames, frame rate and other necessary information from a video file or a live stream

Step 2: Transport our frames over HTTP to the client’s browser.

Step 3: Animate the frames at the client, response to user interaction and request for more frames if needed.

Step 1: Getting the frames, frame rate and other attributes of video clip

If you have experience with writing applications in Microsoft DirectShow Editing Services (codename Dexter), this will sound very familiar to you. In the Windows environment, traditionally capturing still frames has been done using C++ and Dexter Type Library to access DirectShow COM objects. To do this in .NET Framework, you can make an Interop assembly of DexterLib which is listed under COM References in VS 2005. However it takes you a good amount of work to figure out how to convert your code from C++ to C# .NET. The problem occurs when you need to pass in a pointer reference as an argument to a native function, CLR does not directly support pointers as the memory position can change after each garbage collection cycle. You can find many articles on how to use DirectShow on the CodeProject or other places and we try to keep it simple. Here our goal is to convert a video file into an array of Bitmaps and I tried to keep this as short as possible, of course you can write your own code to get the Bitmaps out of a live stream and buffer them shortly before you send them.

Basically we have two option for using the DirectShow for converting our video file to frames in .NET:

- Edit the Interop assembly and change the type references from pointer to C# .NET types.

- Use pointers with

unsafe keyword.

We chose the unsafe (read fast) method. It means that we extract our frames outside of .NET managed scope. It is important to mention that managed does not always mean better and unsafe does not really mean unsafe!

MediaDetClass mediaClass = new MediaDetClass();

_AMMediaType mediaType;

...

int outputStreams = mediaClass.OutputStreams;

outFrameRate=0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < outputStreams; i++)

{

mediaClass.CurrentStream = i;

try{

outFrameRate = mediaClass.FrameRate;

.......

.....

}catch

{

}

if (outFrameRate==0.0)

throw new NotSupportedException( " The program is unable" +

" to read the video file.");

...

unsafe {

...

...

while (currentStreamPos < endPosition)

{

mediaClass.GetBitmapBits(currentStreamPos, ref bufferSize,

ref *ptrRefFramesBuffer,

outClipSize.Width, outClipSize.Height);

...

...

}

}

...

Step 2: Transfer extracted data over HTTP

So far we have converted our video to an array of Bitmap frames. The next step is to transfer our frames over HTTP all the way to the client’s browser. It would be nice if we could just send our Bitmap bits down to the client but we cannot. HTTP is designed to transport text characters which mean your browser only reads characters that are defined in the HTML page character set. Anything else out of this encoding cannot be directly displayed.

To accomplish this step, we use Base64 encoding to convert our Bitmap to ASCII characters. Traditionally, Base64 encoding has been used to embed objects in emails. Almost all modern browsers including Gecko browsers, Opera, Safari, and KDE (not IE!) support data: URI scheme standard to display Base64 encoded images. Great! Now, we have our frames ready to be transferred over HTTP.

System.IO.MemoryStream memory = new System.IO.MemoryStream();

while (currentStreamPos < endPosition)

{

...

vdeoBitmaps.Save(memory, System.Drawing.Imaging.ImageFormat.Jpeg);

strFrameArray[frameCount] = System.Convert.ToBase64String(memory.ToArray());

memory.Seek(0, System.IO.SeekOrigin.Begin);

}

memory.Close();

...

But we cannot just send out the encoded frames as a giant string. We create an XML document that holds our frames and other information about the video and then send it to the client. This way the browser can receive our frames as a DOM XML object and easily navigate through them. Just imagine how easy it is to edit a video that is stored in XML format:

="1.0"="utf-8"

<Clip name="Snoopi">

<Frame_Rate>14.9850224700412</Frame_Rate>

<Clip_Size>{Width=160, Height=120}</Clip_Size>

<Stream_Length>6.4731334</Stream_Length>

<Frame ID="96">/9j/4AAQSkZJRgABAQEAYAB.... </Frame>

....

</Clip>

This format also has its own drawbacks. The videos that are converted to Base64 encoded XML files are somewhere between 10% (mostly AVI files) to 300 % or more (some WMV files) bigger than their binary equivalent.

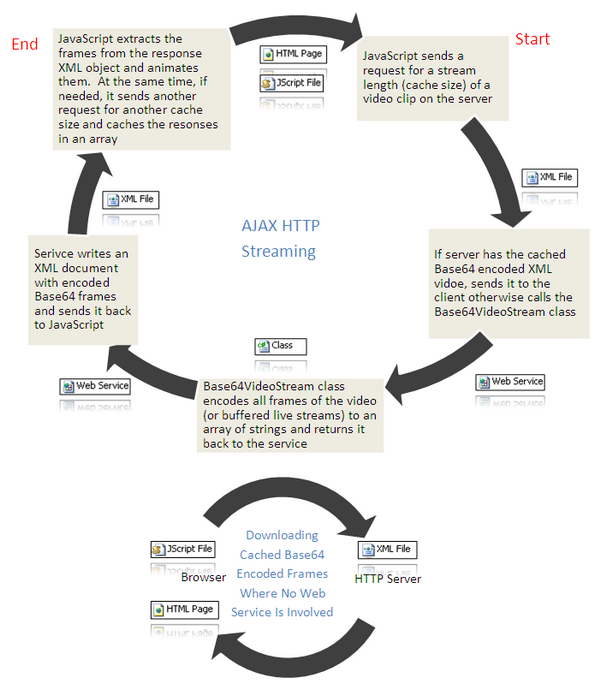

Figure 1 shows the data flow in our AJAX Video Player application.

Figure 1: Data flow in AJAX Video Player

If you are using an XML file, you even don't need a web server , you can open the HTML from a local directory and it should work! I included an executable in the article's download file that can convert your video file to XML document which later can be shown in the browser. However using big files and high resolution videos is not a good idea!

OK, now we can send out our “Base64 encoded video” XML document as we would do with any other type of XML files. Who says XML files always have to be boring record sets anyway?!

Step 3: Animate the frames at the client

Figure 2 shows the application flow in the JavaScript VideoPlayer object. I tried to comment the code as much as possible. You can view the source code in the download provided with this article.

Figure 2: Application flow in AJAX Video Player

Conclusion

In this article, we simulated data streaming with JavaScript and talked about its great potentials to perform the tasks associated with plugins, although it will be a while until it can replace them in real world applications. A more featured JavaScript with better OOP support is beneficial to everybody. When it comes to developing JavaScript features many conservative precautions have been considered just to open the door for all sort of plug-ins! Java to JavaScript compliers have already started to squeeze as much as possible out of JavaScript. Google (GWT) and Mozilla (here) have released great compliers to convert your Java code to JavaScript.

Some time in the future :) in another article we talk about how JavaScript can improve the MVC design pattern of a web application by loosely coupling viewers (HTML pages) and controllers (classes in an XML Service). In some scenarios JavaScript can completely replace your web controls and save you from going through ASPX page life cycle.

Appendix - Related Links