Contents

Model View Presenter (MVP) is a technique of loosely coupling interaction between the layers in an application. Setter and constructor based dependency injection makes it possible to test the code in isolation, without dependency or impact on the runtime host environment. The MVP architecture typically consists of a presenter, service, data and possibly other layers. The typical pattern in MVP consists of a view initializer that could also implement a view interface. Alternatively in a widget oriented design, the view initializer may host multiple widgets each of which implement view interfaces. Each view is tied to a presenter that controls the view. For more information on MVP, please refer to my earlier article on DLINQ (LINQ to SQL), where I have talked about MVP architecture.

Have you wondered about a scenario where multiple presenters handle a single view? What if a view initializer hosts multiple views and there is a dependency between the presenters for initializing state? There could be another variation where multiple presenters handling multiple views may share a model, either partly or completely.

At the heart of the Framework lies a reflection based factory that sets up a linked list of presenters in either of two configurations using attribute based semantics that define dependencies between presenters. The presenter chain implements two flavors of chain propagation - "Chain of responsibility" and "Intercepting filter patterns." The factory loads a set of presenters from a target assembly and generates a linked list of presenters using a dependency parsing algorithm. Dependencies are defined in presenter metadata in the form of dependency attributes that define unary relationships (Head, Tail, Middle) and binary relationship (ComesAfter property) between presenters. A presenter skeleton linked list is constructed one time in the order of defined dependencies using the dependency algorithm. A presenter chain is then generated for each request using metadata from the cached presenter skeleton chain. The lifecycle of the presenter chain layer is similar to that of a single presenter. The presenter chain handles request processing in two modes - "Break" and "Continue." In the break mode, the chain terminates processing and returns control back to the caller as soon as the first node (a presenter) is able to handle the request. Processing in the "continue" mode is similar to that of the intercepting filter pattern where control flows all the way upto the tail of the presenter chain even if an earlier node handled the request.

This Framework is not dependent on the hosting environment. It can be used in ASP.NET, Winforms and other environments. Since presenters are typically (but not required to be) packaged in a separate assembly, the behaviour of the page can be dynamically changed at runtime by either injecting a new presenter assembly into the system or by changing a presenter implementation. The caching infrastructure which caches the presenter skeleton chain picks up this change and loads the new implementation. The framework provides the contract for an MVP implementation that is applicable to this context.

WebCacheItemManager<PresenterSkeletonChain> presenterCache =

new WebCacheItemManager<PresenterSkeletonChain>

(presenterChainCacheKey);

WebCacheItemManager<Dictionary<Type, ConstructorInfo>> ctorMetadataCache =

new WebCacheItemManager<Dictionary<Type, ConstructorInfo>>

(ctorMetadataCacheKey);

PresenterFactory.InitializeFactory

(ctorMetadataCache, presenterCache, assembly);

Presenter head = PresenterFactory.BuildPresenterChain(new DummyWebView(),

PresenterChainMode.Continue);

head.HandleRequest();

Enums

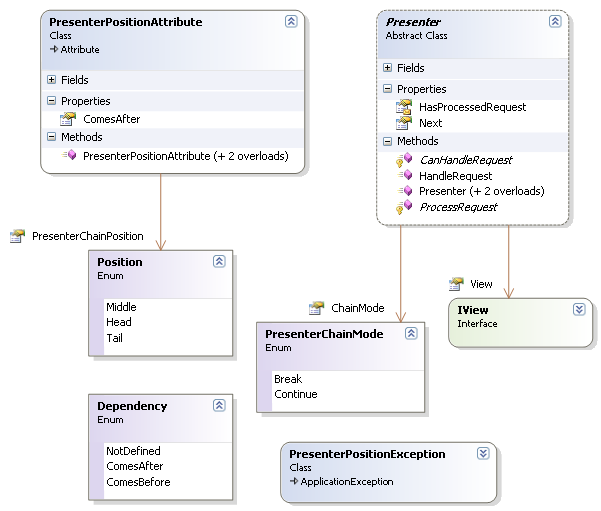

Position: Expresses the relative position of a presenter node in the chain Dependency: Used internally. This enum expresses a binary relationship between two presenter nodes PresenterChainMode: Defines the behaviour of the presenter chain

PresenterPositionAttribute

- Defines the relative position for a presenter within the chain (Head, Tail or Middle [default])

- May optionally define a binary dependency relationship between two nodes (

ComesAfter property)

PresenterSkeleton

Used by the factory to maintain a backbone of the presenter chain. The backbone is cached and subsequent invocations of the factory will use the cached presenter backbone to create a presenter chain that has dependencies on the view and chaining mode.

Inline with dependency injection which is the foundation of an MVP based architecture, the factory defines core interfaces that are host environment independent.

IView: Base view identifier. Clients may define more specialized view interfaces that inherit IView ICacheItemManager<T>: Defines a caching contract that enables strongly typed access to cached objects of different types

public interface ICacheItemManager<T>

{

T Get();

void Put(T item);

string GetCacheKey();

event CacheInvalidatedEventHandler<T> CacheInvalidated;

}

The caching contract defines a CacheInvalidated event of the type CacheInvalidatedEventHandler which is defined as follows:

public delegate void CacheInvalidatedEventHandler<T>

(string key, T value);

The ICacheItemManager implementation is expected to generate this event when the cache store is invalidated.

IControlStore<V> and ISessionStore define fine grained storage contracts at the user session and user interface widget level.

PresenterSkeletonChain

.NET 1.x data structures such as ArrayList, Queue and Stack were array based implementations. If you disassemble the IL for Queue, it is evident that it is implemented as an array. A dependency chain is best implemented as a linked list. Nodes in a linked list need not be contiguous in memory unlike in an array. Re-ordering a linked list involves reordering pointers to individual nodes and not physical insertion and deletion of values into contiguous memory locations as in array based implementations of a linked list. So I was all set to implement my own linked list when I stumbled upon LinkedList<T> in the System.Collections.Generic namespace in .NET Framework 2.

PresenterSkeletonChain is the infrastructure backbone that corresponds to the computed dependency order of presenter nodes in the PresenterChain. The skeleton is generated from a dependency parsing algorithm used by the factory and is then cached. See the caching note for the web implementation of ICacheManager. The PresenterSkeletonChain is stateless unlike the Presenter linked list which has state dependencies on the IView instance, chaining mode and other possible dependencies on the state of the underlying model that it operates on. Hence the Presenter chain follows a unit of work pattern. It is upto the user to define the lifecycle of a Presenter chain. I tend to think that it follows the lifecycle of a Request in web applications and that of a Form in Winforms applications.

Presenter

This represents the actual presenter chain that is built from a PresenterSkeletonChain. It is not a linked list in itself but it is a pointer to another presenter node which collectively forms a singly linked list of presenters. In that sense the head of the presenter chain is a front controller and the client calls HandleRequest on the head of the chain.

The base Presenter class implements two modes of chain propagation depending on the value of the PresenterChainMode parameter that is passed to its constructor. In the "Break" mode it implements the classic GOF chain of responsibility pattern which is similar to the control execution of a switch case statement. Starting from the head, each node in the chain checks if it can handle the execution context. Control is passed to the next node in the chain in case it cannot handle the request. Control returns back to the caller after the first node handles the execution context. In the "Continue" mode, the presenter chain implements an intercepting filter pattern where every node in the chain gets a chance to handle execution irrespective of whether an earlier node processed the request. There is a slight demarcation from the classic intercepting filter. In my pipeline each presenter node first checks to see if it can handle execution before processing the request and then transfers control to the next node in the chain.

Although this closely resembles the ASP.NET pipeline architecture, it is quite different. In the ASP.NET pipeline model, the request is finally handled by a single end point that implements the IHttpHandler interface. The layer of intermediary "filters" do some specialized functionality on the request, but processing is handled only by a single handler.

I would also claim that my design is different from the GOF decorator pattern. A linked list of decorators may be used to implement an intercepting filter pattern wherein control transfers linearly from the outer wrapper object to the wrapped inner object. To add to your confusion, I will introduce another pattern that sounds similar but is not quite the same. Pipes and filters is another variation of the intercepting filter pattern but is mainly used in message queuing architectures. In this case, filters connect to each other via pipes and the output of a filter node is fed as input into the next filter using pipe as a state buffering mechanism. In my chain design, there is no explicit input/output state semantics between nodes although it is possible that all presenters in the chain may act on the same model instance.

In the following code, CanHandleRequest() and ProcessRequest() are abstract methods defined in the abstract base Presenter class. The entry point to the presenter chain is the HandleRequest() method which is called by clients.

public virtual void HandleRequest()

{

if (CanHandleRequest())

{

if (ChainMode == PresenterChainMode.Break)

{

ProcessRequest();

_hasProcessedRequest = true;

return;

}

else { ProcessRequest(); _hasProcessedRequest = true; }

}

if(Next != null) Next.HandleRequest();

}

This class implements the dependency parsing algorithm and does most of the heavy lifting of setting up the presenter chain. Clients interact with it through two of its public methods - InitializeFactory and BuildPresenterChain. Inline with the MVP pattern, ICacheItemManager<Dictionary<Type, ConstructorInfo>> and ICacheItemManager<PresenterSkeletonChain> dependencies are injected into the PresenterFactory in the InitializeFactory method. The presenter assembly dependency is also passed via this method.

The InitializeFactory method sets the PresenterMetadataCacheManager and PresenterChainCacheManager properties which internally wire up the OnCacheInvalidated<T> delegate to the CacheInvalidated event declared in ICacheItemManager<T> .

internal static void OnCacheInvalidated<T>(string key, T value)

{

switch (key)

{

case CACHE_KEY_PRESENTER_METADATA:

GetPresenterMetadata();

break;

case CACHE_KEY_PRESENTER_CHAIN:

GetPresenterSkeletonChain();

break;

}

}

The BuildPresenterChain method is to be called during the "initialization phase" in the view initializer's lifecycle. It takes in the IView dependency along with the chaining mode behavior and returns a new instance of the presenter chain that is constructed using the cached presenter skeleton chain backbone.

The following snippet shows the implementation of thread safety using a pessimistic locking strategy in the PresenterFactory. Since PresenterSkeletonChain and metadata are cached, reads should be fast and locks are held for minimal time. Readers (in GetPresenterXXX methods) and writers (ScanPresenters method) lock over the static _syncLock which prevents dirty reads and race conditions. This pattern is commonly known as double check locking.

New instances of PresenterSkeletonChain and Dictionary<Type, ConstructorInfo> are created by scanning the presenter assembly. This is done only if a cache lookup results in a null value. ICacheItemManager<T> defines a cache invalidation delegate so that implementers are expected to generate a CacheInvalidated event when the cached item is invalidated.

internal static Dictionary<Type, ConstructorInfo> GetPresenterMetadata()

{

Dictionary<Type, ConstructorInfo> ctorInfo =

_presenterMetadataCacheMgr.Get();

if (ctorInfo == null) {

lock (_syncLock)

{

if (_presenterMetadataCacheMgr.Get() == null) ScanPresenters();

ctorInfo = _presenterMetadataCacheMgr.Get();

}

}

return ctorInfo;

}

internal static PresenterSkeletonChain GetPresenterSkeletonChain()

{

PresenterSkeletonChain list = _presenterChainCacheMgr.Get();

if (list == null)

{

lock (_syncLock)

{

if (_presenterChainCacheMgr.Get() == null) ScanPresenters();

list = _presenterChainCacheMgr.Get();

}

}

return list;

}

The assembly MVPChainingFactory.Web.dll implements a Web version of the interfaces defined in the MVPChainingFactory framework (MVPChainingFactory.dll). The namespace MVPChainingFactory.Caching.Web defines WebCacheItemManager<T> which is a web implementation of ICacheItemManager<T>. The following snippet shows the implementation of the Put method that puts an item into the cache. Presenters are contained in a separate assembly. A CacheDependency is created on the presenter assembly which is wired to an anonymous delegate that implements the CacheItemRemovedCallback. This mechanism is used to refresh the cached PresenterSkeletonChain when the assembly containing presenters is modified.

public void Put(T item)

{

string key = GetCacheKey();

Cache c = HttpRuntime.Cache;

Assembly a = Assembly.Load(CacheDependencyAssembly);

CacheDependency dep = a != null ? new CacheDependency(a.Location) : null;

if (c[key] == null)

{

c.Insert(key,

item,

dep,

Cache.NoAbsoluteExpiration,

Cache.NoSlidingExpiration,

CacheItemPriority.Default,

delegate(string k, object v, CacheItemRemovedReason reason)

{

CacheInvalidatedEventHandler<T> e = _events[_eventKey] as

CacheInvalidatedEventHandler<T>;

T value = v as T;

if (e != null)

e(k, value);

}

);

}

}

The anonymous delegate generates the CacheInvalidated event when the cached item gets invalidated (triggered when the presenters assembly is modified). WebCacheItemManager<T> implements CacheInvalidated event as follows:

public event CacheInvalidatedEventHandler<T> CacheInvalidated

{

add { _events.AddHandler(_eventKey, value); }

remove { _events.RemoveHandler(_eventKey, value); }

}

Dependencies are expressed using the PresenterPositionAttribute. As explained earlier in the section Engine parts: Metadata, dependencies can be expressed as binary relationships or as positions within the presenter chain. Two core functions infer the two types of dependencies.

InferRDependentFromPositionMetadata returns the chain position metadata of a node.

internal static Dependency InferRDependentFromPositionMetadata

(PresenterSkeleton node, bool isRNode)

{

PresenterPositionAttribute atr = GetPresenterPositionMetadata

(node.PresenterType);

Position pos = atr == null

? Position.Middle : atr.PresenterChainPosition;

if (pos == Position.Head)

{

node.PresenterPosition = Position.Head;

return isRNode ? Dependency.ComesBefore : Dependency.ComesAfter;

}

else if (pos == Position.Tail)

{

node.PresenterPosition = Position.Tail;

return isRNode ? Dependency.ComesAfter : Dependency.ComesBefore;

}

return Dependency.NotDefined;

}

IsRDependent infers the binary relationship between two nodes. The parameter isRAlreadyPresentInList is used as a hint to define a default behaviour if there is no explicit binary relationship defined between nodes. IsRDependent depicts a directed dependency from an L node to an R node if the result is Dependency.ComesAfter (indicating that R comes after L). The function returns Dependency.ComesBefore indicating that R comes before L, if no explicit chain position or binary dependency definitions were found and isRAlreadyPresentInList is true. If R is not already present in the chain and there are no explicit dependencies, then R is inserted in a FIFO manner at the very end of the presenter chain.

internal static Dependency IsRDependent

(PresenterSkeleton l, PresenterSkeleton r, bool isRAlreadyPresentInList)

{

if (l.PresenterType.FullName == r.PresenterType.FullName)

return Dependency.NotDefined;

Dependency d = InferRDependentFromPositionMetadata(r, true);

if (d != Dependency.NotDefined) return d;

d = InferRDependentFromPositionMetadata(l, false);

if (d != Dependency.NotDefined) return d;

PresenterPositionAttribute rAtr =

GetPresenterPositionMetadata(r.PresenterType);

PresenterPositionAttribute lAtr =

GetPresenterPositionMetadata(l.PresenterType);

Type rComesAfter = rAtr == null ? null : rAtr.ComesAfter;

Type lComesAfter = lAtr == null ? null : lAtr.ComesAfter;

if (rComesAfter != null && rComesAfter.FullName ==

l.PresenterType.FullName)

return Dependency.ComesAfter;

if (lComesAfter != null && lComesAfter.FullName ==

r.PresenterType.FullName)

return Dependency.ComesBefore;

return isRAlreadyPresentInList ? Dependency.ComesBefore :

Dependency.ComesAfter;

}

I came up with a dependency parsing algorithm which is implemented partly in PresenterFactory and the remainder in PresenterSkeletonChain. Please refer to the Architecture section that follows, for a better understanding on how the supplied code is organized and how I visualize its integration with client code. PresenterFactory scans the target assembly that contains a set of presenters and supplies the attribute based dependency definitions to the dependency parsing algorithm.

Two types of binary dependency relationships may be defined relative to a node:

- The reference node comes after another node (Na -> Nr)

- Another node comes after the reference node (Nr -> Na)

PresenterFactory scans the presenter assembly and picks up any derived implementations of the abstract Presenter class. A newly picked up presenter that is yet to be linked in the chain is first compared with the current "head". If the head is a dependent (defined by the ComesAfter binary relationship) then the new node is attached in front of the head, making it the new head of the chain and creating a directed link from the new node to the previous head. This step takes care of the second type of dependency relationship cited above. To check for the first type, the remainder of the chain is scanned to find a potential predecessor for the newly inserted node. If a binary relationship of the first type is found w.r.t. a node in the remainder set, that node is positioned in front of the newly inserted node and the links are readjusted. There is no need to scan any further after finding the first match because relationships are binary. If there is no binary relationship between the new node and the current head, the above logic is applied to the head's successor node, and so on.

internal static void ScanPresenters()

{

Dictionary<type, /> metadata = new Dictionary<type, />();

PresenterSkeletonChain presenterList = new PresenterSkeletonChain();

int headCount = 0, tailCount = 0;

lock (_syncLock)

{

Assembly a = Assembly.Load(PresenterAssembly);

foreach (Type t in a.GetTypes())

{

Type baseType = t.BaseType;

if (t.IsClass)

{

while (baseType != typeof(Object) && baseType != null)

{

if (baseType == typeof(Presenter) && baseType.IsAbstract)

{

Position p = GetPresenterPositionFromAttrib(t);

ValidateHeadOrTailDefinition

(ref headCount, ref tailCount, p);

LinkedListNode<presenterskeleton /> current =

ConstructSkeletonNode(t, metadata);

LinkedListNode<presenterskeleton /> head = presenterList.First;

if (head == null) presenterList.AddFirst(current);

else

{

if (IsRDependent(current, head, true) ==

Dependency.ComesAfter)

{

presenterList.AddBefore(head, current);

presenterList.AdjustLinks(current, head);

break;

}

else

presenterList.InsertPresenter

(head, current, false);

}

}

baseType = baseType.BaseType;

}

}

}

_presenterChainCacheMgr.Put(presenterList);

_presenterMetadataCacheMgr.Put(metadata);

}

}

PresenterSkeletonChain implements the core of the dependency parsing algorithm.

public virtual void InsertPresenter(

LinkedListNode<PresenterSkeleton> referenceNode,

LinkedListNode<PresenterSkeleton> newNode,

bool newNodeBeforeReference)

{

if(newNode.Value.PresenterPosition == Position.Head)

{

base.AddFirst(newNode);

return;

}

if (newNode.Value.PresenterPosition == Position.Tail)

{

base.AddLast(newNode);

return;

}

LinkedListNode<PresenterSkeleton> target = newNodeBeforeReference

? referenceNode.Previous : referenceNode.Next;

Dependency d = Dependency.NotDefined;

if (target != null && ((d = PresenterFactory.IsRDependent

(target, newNode, false))

== Dependency.NotDefined))

{

target = target.Next;

d = PresenterFactory.IsRDependent(target, newNode, false);

}

if (target != null && d == Dependency.ComesAfter) {

InsertPresenter(target, newNode, false);

return;

}

if (target != null && d == Dependency.ComesBefore) {

base.AddBefore(target, newNode);

AdjustLinks(newNode, target);

return;

}

if(newNodeBeforeReference) base.AddBefore(referenceNode, newNode);

else base.AddAfter(referenceNode, newNode);

}

In the following function, lNode is a new node that has just been added before rNode. This function checks the remainder set of nodes to the right of rNode to see if there is a binary relationship defined w.r.t. lNode. Pointers are re-adjusted if there is a ComesAfter relationship. It may be noted that when there is no binary relationship defined between lNode and rNode, the function IsRDependent indicates a default relationship where the lNode comes before the rNode. Hence this case does not result in any link adjustment.

public void AdjustLinks(LinkedListNode<PresenterSkeleton> lNode,

LinkedListNode<PresenterSkeleton> rNode)

{

if (lNode.Value.PresenterPosition != Position.Middle) return;

LinkedListNode<PresenterSkeleton> curr = rNode.Next;

while (curr != null)

{

if (PresenterFactory.IsRDependent(curr, lNode, true) ==

Dependency.ComesAfter)

{

base.Remove(curr);

base.AddBefore(lNode, curr);

break;

}

curr = curr.Next;

}

}

A best case scenario is when a new type that is scanned from the assembly does not have an explicit relation defined w.r.t. the current head in the presenter chain, but the head's immediate successor type has a ComesAfter relation defined w.r.t. the new type. This situation will result in the insertion of a new node just after the head with each iteration. The complexity involves two comparisons per step and is O(n), where n is the number of presenter types in the presenter assembly. A worst case scenario arises when there are no dependency relationships defined. This results in the traversal of the entire chain to insert a node on every iteration. The worst case complexity is thus (1 + 2+ 3 +.... n-1) which is O(n^2) [more precisely n/2*(n+1)].

A more efficient approach for dependency parsing may be done through the use of a graph data structure and the "Topological sort" algorithm. A directed edge in the graph represents a dependency relationship between two vertices. This algorithm involves constructing a graph and traversing it starting with the node that has no incoming edges. Running time is linear [O(V+E) where V is the number of vertices and E is the number of edges]. One may use QuickGraph for graph data structure and algorithm implementations. QuickGraph is a .NET port of the popular Boost Graph Library for C++. In fact, I have contributed transitive closure and condensation graph algorithm implementations to QuickGraph. Digressing a little from the topic, transitive closure is an algorithm with far reaching implications for software development. It is used by refactoring tools and also for static code analysis. However in the MVPChainingFactory Framework, I cache the dependency list after applying my algorithm. Also run time becomes significant when the number of presenters is infinitely large, which is hardly the case in common MVP applications. I must admit that I got a bigger kick by coming up with my own algorithm as compared to using QuickGraph, as this was a "hobby" project.

The diagram below illustrates the architecture of a website that is implemented using the MVPChainingFactory Framework. However, it is to be noted that the MVPChainingFactory Framework can be used in web as well as other environments such as WinForms. A related DLL (MVPChainingFactory.Web.dll) contains web specific implementation of the dependency contracts defined in the MVPChainingFactory Framework (MVPChainingFactory.dll). The website references this DLL. Non web clients may reference only the core MVPChainingFactory.dll to access the Framework. Presenters.dll contains a set of presenters that implement the abstract Presenter class that is defined in MVPChainingFactory.dll. These concrete classes are marked with PresenterPositionAttribute to express dependencies.

Unit testability is the main focus of MVP design. This framework does not make any assumptions about the host environment. I have used Rhinomocks to mock dependencies for unit testing. The unit tests are not restricted to public interface methods alone. One pattern for testing non public methods is to use reflection to invoke private or protected methods in a framework class from unit tests. The benefits include fine grained control over member accessibility in the framework classes. The trade off is the ability to refactor (rename) members, which would involve a search and replace operation instead of the reliable object graph mechanism used by refactoring tools. Alternatively, the design of Framework classes could be modified to use the internal keyword for all non public methods that need to be unit tested. I have used this approach by marking the Framework assembly with the InternalsVisibleTo attribute.

My unit tests are organized into two logical categories - "Factory API" and "Factory load order" (by specifying CategoryAttribute). The former deals with the Factory API and functionality while the latter tests if the generated presenter chain confirms to the dependency relationships defined in unit tests. I follow a common pattern across both test categories, which is to create mock objects and setup common expectations in the setup method. I will highlight a couple of interesting tests. The remainder can be found within the source code in the MVPChainingFactory.Tests project.

[SetUp]

public void Setup()

{

_rep = new MockRepository();

_mockMetadataCacheManager =

_rep.CreateMock<ICacheItemManager<Dictionary<Type,

ConstructorInfo>>>();

_mockPresenterChainCacheManager =

_rep.CreateMock<ICacheItemManager<PresenterSkeletonChain>>();

_mockMetadataCacheManager.CacheDependencyAssembly = null;

LastCall.Constraints(Is.Equal(_assemblyName));

_mockMetadataCacheManager.CacheInvalidated += null;

_cmEvt = LastCall.IgnoreArguments().GetEventRaiser();

_mockPresenterChainCacheManager.CacheDependencyAssembly = null;

LastCall.Constraints(Is.Equal(_assemblyName));

_mockPresenterChainCacheManager.CacheInvalidated += null;

_pccmEvt = LastCall.IgnoreArguments().GetEventRaiser();

}

In the above snippet, I get a reference to IEventRaiser on the mocked objects in order to simulate and test the callback functionality of the CacheInvalidated event as follows:

PresenterSkeletonChain p = new PresenterSkeletonChain();

Dictionary<Type, ConstructorInfo> d = new Dictionary<Type,ConstructorInfo>();

using (_rep.Record())

{

Expect.Call(_mockPresenterChainCacheManager.Get()).Return(p);

Expect.Call(_mockMetadataCacheManager.Get()).Return(d);

}

using (_rep.Playback())

{

PresenterFactory.InitializeFactory(_mockMetadataCacheManager,

_mockPresenterChainCacheManager, _assemblyName);

_pccmEvt.Raise(PresenterFactory.CACHE_KEY_PRESENTER_CHAIN, p);

_cmEvt.Raise(PresenterFactory.CACHE_KEY_PRESENTER_METADATA, d);

}

The following test snippet checks the caching pattern that I have used in the Framework. Get accessors should first do a lookup on the cache and return the cached instance on a hit. The PresenterFactory.PresenterSkeletonChain property accessor should re-scan the assembly and refresh the cache on a miss. The following code tests the call stack and ensures the above "double check lock" pattern when a cache lookup results in a miss. The first two calls to _mockPresenterChainCacheManager.Get() simulate a cache miss which results in a scan of the presenter assembly. The PutSimulator delegate intercepts the call to _mockPresenterChainCacheManager.Put and obtains a reference to the argument. The final call to Get, which is after the assembly scan is mocked to return the dummy chain.

PresenterSkeletonChain dummyChain = new PresenterSkeletonChain();

dummyChain.AddLast(new LinkedListNode<PresenterSkeleton>(

new PresenterSkeleton(typeof(object))));

PresenterSkeletonChain actualHead = null;

using (_rep.Record())

{

Expect.Call

(_mockPresenterChainCacheManager.Get()).Return(null).Repeat.Twice();

_mockPresenterChainCacheManager.Put(null);

LastCall.Constraints(Is.NotNull()).Do((PutSimulator)

delegate(PresenterSkeletonChain head)

{

actualHead = head;

return;

}

);

_mockMetadataCacheManager.Put(null);

LastCall.Constraints(Is.NotNull());

Expect.Call(_mockPresenterChainCacheManager.Get()).Return(dummyChain);

}

PresenterSkeletonChain ret = null;

using (_rep.Playback())

{

PresenterFactory.InitializeFactory

(_mockMetadataCacheManager, _mockPresenterChainCacheManager,

_assemblyName);

ret = PresenterFactory.PresenterSkeletonChain;

}

Assert.IsNotNull(ret);

I have formulated a few use cases for testing that vary in the level of complexity in expressing chain dependencies. Each test use case is bundled into a separate presenter stub assembly that contains a set of stub presenters along with attribute metadata for expressing dependency relationships. Unit tests that deal with a particular use case reference the corresponding presenter stub assembly. The Architecture section describes the logical tiers and interaction.

The following is a test of one of the use cases defined in StubPresentersUsecase1.dll. In this test, I convert the generated presenter chain to a generic List<Type> and verify the expected order of presenters in the chain by comparing indices.

[Test]

public void TestPresenterLoadAndOrderingOfUsecase1()

{

string _assemblyName = "StubPresentersUsecase1";

int countOfPresenters = 6;

PresenterSkeletonChain p = null;

using (_rep.Record())

{

_mockPresenterChainCacheManager.Put(null);

LastCall.Constraints(Is.NotNull()).Do((PutSimulator)

delegate(PresenterSkeletonChain head)

{

p = head;

return;

}

);

_mockMetadataCacheManager.Put(null);

LastCall.Constraints(Is.NotNull());

}

using (_rep.Playback())

{

PresenterFactory.InitializeFactory

(_mockMetadataCacheManager, _mockPresenterChainCacheManager,

_assemblyName);

PresenterFactory.ScanPresenters();

}

string mesg = "Expected count={0}, actual count={1}";

Assert.IsNotNull(p);

Assert.AreEqual(countOfPresenters, p.Count,

String.Format(mesg, countOfPresenters, p.Count));

mesg = "Expected presenter type at position {0}={1}, Actual={2}";

List<Type> orderOfPresenters = ToList(p);

Assert.AreEqual(typeof(P3), orderOfPresenters[0],

String.Format(mesg, 0, typeof(P3), orderOfPresenters[0]));

Assert.AreEqual(typeof(DefaultPresenter), orderOfPresenters[5],

String.Format(mesg, 0, typeof(DefaultPresenter),

orderOfPresenters[5]));

mesg = "Expected that {0} comes after {1}.

Actual index of {0} = {2} and {1} = {3}";

int l = 0, r = 0;

l = orderOfPresenters.IndexOf(typeof(P4));

r = orderOfPresenters.IndexOf(typeof(P2));

Assert.Less(l, r, String.Format(mesg, typeof(P2), typeof(P4), r, l));

l = orderOfPresenters.IndexOf(typeof(P5));

r = orderOfPresenters.IndexOf(typeof(P4));

Assert.Less(l, r, String.Format(mesg, typeof(P4), typeof(P5), r, l));

}

The MVPChainingFactory Framework uses a dependency parsing algorithm to generate a linked list of presenters in the order of defined dependency. The linked list forms a layer of presenters whose behavior can be configured as either a chain of responsibility or intercepting filter implementation. Although the design of my dependency parsing infrastructure is centered around a set of presenters, the idea can be applied to other areas as well with some code extensions. One such candidate could be a service layer consisting of a linked list of services ordered by dependency which is used within a presenter.