Introduction

A firm understanding of multithreaded programming is crucial for successful Windows programming. While Microsoft provides information for standard threaded programming through MSDN topics such as Processes and Threads [1], at times, more information is desired so that one may take advantage of non-procedural programming techniques.

Jeffrey Richter discusses when and why to create a thread, and when not to create a thread [2]. This article will discuss how one can misuse threads while exploring Operating System data structures associated with threads. The misuse will be coined 'Rabbit Threads' (a neologism introduced by Peter Szor) in spirit with the use of the term rabbit (which hops around) to describe a computer virus which lives on the host in favor of another.

Definitions

The following is a brief summary of the terms used throughout this article. Anyone who has attended a Mathematics conference should appreciate the brevity.

Program

A program is a static on-disk representation of a process. When a program is executed, it becomes a process [3]. Russinovich and Solomon provide a detailed discussion of process creation in Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP, and Windows 2000 [4].

Process

Jeffrey Richter describes a process as an instance of a running program [5]. Each process provides the resources needed to execute a program. A process has a virtual address space, executable code, open handles to system objects, a security context, a unique process identifier, environment variables, a priority class, minimum and maximum working set sizes, and at least one thread of execution [6].

Thread

A thread is the entity within a process that can be scheduled for execution by the Operating System [7]. Each thread maintains user and kernel stack areas, exception handlers, a scheduling priority, thread local storage, a unique thread identifier, and a set of structures the system will use to save the thread context until it is scheduled [8]. On x86 Windows NT, the kernel stack size is 12 KB, while x64 platforms enjoy a 24 KB kernel stack [9].

Fiber

A fiber is a unit of execution that must be manually scheduled by the application. Fibers run in the context of the threads that schedule them [10]. Fibers were added to Windows to assist in porting UNIX server applications to Windows [21].

PCB

Process Control Block or Kernel Process Block. The PCB is a KPROCESS structure, which is part of the EPROCESS data structure. The structure is used by the kernel to schedule threads.

EPROCESS

Executive Process Block is the Windows kernel data structure which represents a process [11]. This structure is accessible through the PsLookupProcessByProcessId function [12].

ETHREAD

Executive Thread Block is the Windows kernel data structure which represents a thread [13]. This structure is accessible through the PsLookupProcessByThreadId function [14].

PEB

The Process Environment Block contains information such as environmental variables [15] and the TLS (Thread Local Storage) array [16]. However, because the PEB contains information which may be modified by the program, it lies in the process address space [17]. A pointer to the PEB may be obtained through the EPROCESS block.

TEB

The Thread Environment Block is part of the ETHREAD data structure [15]. Because the TEB contains information which may be modified by the program, it lies in the process address space [16].

WinDbg

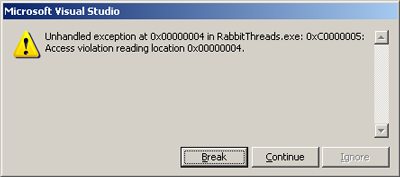

WinDbg and kd will be used to investigate the kernel's management of threads. A kernel debugger such as windbg or kd is required because it is desired to view objects and structures which are not available in the user area. Because these objects are kernel objects, Visual Studio does not know how to interpret their data. In addition, Visual Studio 2005 does not cope well with the techniques that follow. Finally, the method results in a "sp-analysis failed" from IDA Pro when building a call graph for analysis.

Basic WinDbg use was introduced in An Analysis of the Windows PE Checksum Algorithm [19]. The following will extend the discussion. To examine the kernel object associated with processes and threads, start WinDbg. Accept the default parameters as they do not affect the local debug session. Before clicking OK, select the Local tab. Otherwise, WinDbg will attempt to establish a connection on a COM port. Refer to figures 2 and 3. Note that initiating a Kernel Debug session will allow the use of the debugger. Otherwise, one would have to load an executable to have access to the Command window.

| |

|

Figure 2: Starting a kKernel Debug Session

| | Figure 3: Local Debugging

|

The structures of interest for this article are EPROCESS and ETHREAD. To view the ETHREAD structure, issue the dt _ethread command. dt is the Display Types command. Refer to Figure 4.

Figure 4: ETHREAD Structure

The values to the left of the members are the hexadecimal offsets of the members. Some members, such as the Tcb, are structures. To recurse a substructure, issue the same command with recursion: dt -r _ethread. To specify levels of recursion, provide an argument with the switch. For example, -r1 or -r3. Refer to Figure 5.

Figure 5: Substructure Enumeration

Multithreaded Programming

The following example is a typical multithreaded program. The program creates a worker thread which simply exits. It also demonstrates basic synchronization and the proper release of the acquired thread resource handle. This will provide a baseline for investigating threading behavior. The CretateThread() documentation may be found in MSDN [17].

For those who are not interested in WinDbg exploration or already understand the basic example, please skip to 'Rabbit Threads 2' below.

int main( ) {

HANDLE hWorkerThread = NULL;

DWORD dwWorkerThreadID = 0;

hWorkerThread = CreateThread( NULL, 0,

reinterpret_cast< LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE >( ThreadProc ),

NULL, CREATE_SUSPENDED, &dwWorkerThreadID );

if( hWorkerThread == NULL ) { return -1; }

ResumeThread( hWorkerThread );

WaitForSingleObject( hWorkerThread, INFINITE );

CloseHandle( hWorkerThread );

return 0;

}

And the corresponding worker thread procedure:

DWORD WINAPI ThreadProc( LPVOID lpParameter ) {

return 0;

}

Conceptually, the program flow can be depicted as in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Program Flow

Rabbit Threads 1

Though example one is trivial, it will be used to get familiar with a live target under WinDbg, and provide background for later examples.

To examine the program flow in WinDbg, open the executable from the File menu. Next, set a breakpoint on main to skip nonessential initializations. To determine the proper function, issue dt RabbitThreads!*main*. From Figure 7, it is apparent the breakpoint should be set at wmain, so issue bp RabbitThreads!wmain. Alternately, one can issue either bp 0x0041000 or bp wmain.

Figure 7: Determining Breakpoint Location for main()

Finally, breakpoints can be set as follows on thread entrancy points:

0:000> bp wmain

0:000> bp ThreadProc

0:000> bl

0 e 00401000 0001 (0001) 0:**** RabbitThreads!wmain

1 e 00401540 0001 (0001) 0:**** RabbitThreads!ThreadProc

Pressing F5 or typing 'g' in the Command Window will cause the program to run until the breakpoint at wmain is reached. Once the breakpoint fires, WinDbg will also display the source listing, if available. Refer to Figure 8.

Figure 8: wmain() Breakpoint and Source Code

PEB

With the program execution stopped at wmain(), issue !peb to view the Process Environment Block. Figure 9 is the output of the command issued from the Command Browser ( ).

).

Figure 9: Process Environment Block

For a verbose output with offsets, one can issue dt -r _PEB 0x7FFDC000 to dump the memory at 0x7FFDF000 as the Process Environment Block (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Raw Process Environment Block

TEB

The Thread Environment Block can be examined using !teb. Notice the Self field specifying 0x7FFDF000. Refer to Figure 11.

Figure 11: Thread Environment Block

To view the raw memory, issue dt -r _TEB 0x7FFDF000. Refer to Figure 12.

Figure 12: Raw Thread Environment Block

Restarting the program and breaking after thread creation, two threads exist: the primary thread (executing wmain()), and the worker thread (executing ThreadProc()). The Thread Status Command ('~') displays information related to the two threads which are suspended due to breakpoints. Note that Thread 1 has a period ('.') to the left. This signifies the active thread, so commands issued which affect a thread will use the thread 0x84C. This is known as the thread context. Additionally, the context will be displayed at the Command Window prompt: 0:000> signifies the thread 0, while 0:001> signifies thread 1. Refer to Figure 13.

Figure 13: WinDbg Thread Status Command

0x8F4 (2292) is the Process ID. The first thread's ID is 0xDE4, and the second thread's ID is 0x84C. This is confirmed by using the Process Explorer as below (Figure 14). Note that 0x84C = 2124 while 0xDE4 = 3556. When observing the PID and TID in the various kernel structures, they are internally referred to as a ClientID (CID). According to Russinovich and Solomon, this is because the same namespace is used to generate both PIDs and TIDs [20].

Figure 14: Process Explorer View

At this point, issuing !handle shows the handle table of the process (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Process Handle Table

After the thread which is executing main() calls CloseHandle( hWorkerThread ), the usage count on the worker thread is decremented to 0, allowing the Operating System to reclaim the resources. Refer to Figure 16.

Figure 16: Process Handle Table

Rabbit Thread 2

The second sample will demonstrate a single threaded application accessing the next instruction by way of a push/ret pair. The push/ret pair is depicted by the loop below. The pair keeps the stack balanced so that an additional adjustment is not required. Conceptually, Figure 17 depicts the program flow.

Figure 17: Program Flow

Below is the C++ source code with inline assembly which accomplishes the task. LOCATION is resolved to an address. When the compiler encounters the label LOCATION, its name (LOCATION) and address are added to a table for code generation.

int main( )

{

DWORD dwProcessID = 0;

DWORD dwPrimaryThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwLocation = NULL;

dwProcessID = GetCurrentProcessId();

cout << _T("Process ID = 0x");

HEXADECIMAL_OUTPUT(4);

std::tcout << dwProcessID << endl;

dwPrimaryThreadID = GetCurrentThreadId();

cout << _T("Primary thread ID = 0x");

HEXADECIMAL_OUTPUT(4);

cout << dwPrimaryThreadID << endl;

__asm {

push eax

mov eax, LOCATION

mov dwLocation, eax

pop eax

}

cout << _T("Target return address = 0x");

HEXADECIMAL_OUTPUT(8);

cout << dwLocation << endl;

__asm {

push LOCATION

ret

}

LOCATION:

return 1;

}

Using a CONTEXT structure with GetThreadContext() and SetThreadContext() proved to be more difficult than inline assembly using labels. When fetching or setting a context, the thread must be suspended. In addition, there was no comfort in using the functions since portability was abandoned implicitly by using the CONTEXT structure.

The assembler code below is not required for program execution. It is required because the compiler issues a C2451 error when attempting to send LOCATION directly to cout.

__asm {

push eax

mov eax, LOCATION

mov dwLocation, eax

pop eax

}

Verifying correct program execution using WinDbg is shown in Figure 18. The upper right window is the Source Code window. Under the debugger, the ret instruction of the inline assembly will be the next instruction executed. The lower Command Windows displays the address, which the program will begin executing upon transfer of control (0x004011C7). The final window is the Disassembly window. Note from the Disassembly window that the program begins preparing the return value of 1 at location 0x004011C7.

Figure 18: Program Execution with WinDbg

IDA Pro successfully graphs this thread when analyzing the program flow. However, IDA Pro incorrectly labels the code segment loc_4011C9, rather than loc_4011C7. In Figure 19, the larger node is main(), and the smaller node is the code equating to return 1. The right hand figure is the improper labeling of the code.

| |

|

Figure 19: IDA Pro Analysis

|

Rabbit Threads 3

The third example combines the first two examples. The sample will demonstrate a worker thread which rabbits out to execute the primary thread's code. It will also exit by way of the primary thread's code (through main()), rather than its own ThreadProc() shown to the right. Conceptually, this is presented in Figure 20.

Figure 20: Program Flow

int main( )

{

HANDLE hWorkerThread = NULL;

DWORD dwProcessID = 0;

DWORD dwPrimaryThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwWorkerThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwExitArea = NULL;

__asm {

push eax

mov eax, EXITAREA

mov dwExitArea, eax

pop eax

}

hWorkerThread = CreateThread( NULL, 0,

reinterpret_cast< LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE >( ThreadProc ),

reinterpret_cast< LPVOID> ( &dwExitArea ),

CREATE_SUSPENDED, &dwWorkerThreadID );

if( hWorkerThread == NULL ) { return -1; }

ResumeThread( hWorkerThread );

WaitForSingleObject( hWorkerThread, INFINITE );

CloseHandle( hWorkerThread );

EXITAREA:

return 1;

}

The noteworthy addition to this code is the inline assembly to determine the location for execution before the call to CreateThread(). This was required since the location is being passed as a parameter to the worker thread's ThreadProc. In keeping with the prototype of ThreadProc, a pointer to the location is being passed to ThreadProc, rather than the location itself. Shown below is the worker thread's code:

DWORD WINAPI ThreadProc( LPVOID lpParameter )

{

DWORD dwLocation = NULL;

if( NULL == lpParameter ) { return -2; }

dwLocation = * ( reinterpret_cast< DWORD* > ( lpParameter ) );

__asm {

push dwLocation

ret

}

return 1;

}

Execution of the code is as expected - the worker thread begins executing code located in main() after the ret. Below is the graph of main() from IDA. The additional labels were added to aid in visualization. Again, a slight mislabeling occurred. Refer to Figure 21.

Figure 21: IDA Pro Analysis of main()

IDA Pro claims SP-Analysis failed when generating the graph of ThreadProc (Figure 22).

Figure 22: IDA Pro Analysis of ThreadProc()

Rabbit Threads 4

Demonstration four will build upon three so that the worker thread exits using ThreadProc after being mildly promiscuous. While the worker is in main(), it will print a message stating such, and then hop back into its code context. Its depiction is shown in Figure 22.

Figure 22: Program Flow

Below is the primary thread's code. There is one addition: a test to determine which thread is executing. If the currently executing thread is the worker thread, a ret is executed.

if( GetCurrentThreadId() == dwWorkerThreadID )

{

_asm ret

}

The return is examined in detail in ThreadProc.

int main( )

{

HANDLE hWorkerThread = NULL;

DWORD dwProcessID = 0;

DWORD dwPrimaryThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwWorkerThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwCurrentThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwLandingArea = NULL;

__asm {

push eax

mov eax, LANDINGAREA

mov dwLandingArea, eax

pop eax

}

hWorkerThread = CreateThread( NULL, 0,

reinterpret_cast< LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE >( ThreadProc ),

reinterpret_cast< LPVOID> ( &dwLandingArea ),

CREATE_SUSPENDED, &dwWorkerThreadID );

if( hWorkerThread == NULL ) { return -1; }

ResumeThread( hWorkerThread );

WaitForSingleObject( hWorkerThread, INFINITE );

CloseHandle( hWorkerThread );

LANDINGAREA:

dwCurrentThreadID = GetCurrentThreadId();

cout << _T("Executing main function thread ID = 0x");

HEXADECIMAL_OUTPUT(4);

cout << dwCurrentThreadID << endl;

if( GetCurrentThreadId() == dwWorkerThreadID )

{

_asm ret

}

return 1;

And, the corresponding ThreadProc function is shown below. To prepare for the ret to be executed in main(), the desired return address is placed on the worker thread's stack while still in ThreadProc.

DWORD WINAPI ThreadProc( LPVOID lpParameter )

{

DWORD dwExitAddress = NULL;

if( NULL == lpParameter ) { return -2; }

dwExitAddress = * ( reinterpret_cast< DWORD* > ( lpParameter ) );

__asm {

push RETURNAREA

push dwExitAddress

ret

}

RETURNAREA:

DWORD dwCurrentThreadID = GetCurrentThreadId();

cout << _T("Exiting worker function thread ID = 0x");

HEXADECIMAL_OUTPUT(4);

cout << dwCurrentThreadID << endl;

return 2;

}

Figure 23 is the result of running sample four. Notice that both thread exited though main(). The problem lies with dwWorkerThread. dwWorkerThread is a memory location. The code which was generated by the compiler implicitly expected the location to be at a certain relative address in the context of the primary thread. The worker thread retrieved the value of dwWorkerThread using the worker's stack, which proved to be an incorrect value.

Figure 23: Program Results

Figure 24 reveals the generated code which is causing the incorrect program results.

Figure 24: Relative Base Address of dwWorkerThread

According to WinDbg, dwWorkerThread is located at the Relative Base Address of EBP-8. This would be true if the stack were that of the primary thread. Dumping the memory of the worker thread at EBP-8 reveals a value of 0x0050FFAC. Dereferencing offers a value of 004012D8. This is clearly not a thread ID - it appears to be an address in the process space. For completeness, a second dereference was performed on 0x004012D8, resulting in 300015FF. Refer to Figure 25.

Figure 25: Worker Thread Stack

Further investigation showed that 0x004012D8 is the first byte of the instruction sequence FF1500304000 - call dword ptr [GetCurrentThreadId].

To resolve this issue, the test will be changed to the following. There is a small chance this too will produce an incorrect result. However, not nearly as often as the previous test - the previous test returned an incorrect result nearly every time.

if( GetCurrentThreadId() != dwPrimaryThreadID )

An additional solution could have been obtained by making dwWorkerThread a global variable. However, as a Computer Science freshman knows, a global variable is an inappropriate solution.

For the same reason that dwWorkerThread was incorrect, the following would incorrectly overwrite a value in the worker thread's stack. This is because dwCurrentThread would be based upon code generated for the primary thread (relative to EBP of the primary thread):

dwCurrentThread = GetCurrentThreadId();

if( dwCurrentThread != dwPrimaryThreadID )

...

The modified code results are shown in Figure 26. Notice how each thread claims to be "Executing main function", and that the worker thread exits from its procedure, and the primary thread exits through main.

Figure 26: Proper Program Execution

As with previous examples, IDA did not complete the visualization of main. In addition, the label should have been loc_4013F9 rather than loc_4013FE. A similar situation occurred with respect to ThreadProc.

Figure 27: IDA Pro Visualization of main()

Rabbit Threads 5

Example 5 removes the ambiguity of Example 4 by providing the correct value for the thread's ID. It accomplishes this by mirroring the stack frame of the primary thread. Note that there will be differences in the values of the variables when comparing the frames (such as return addresses). What is of interest is the local variable allocations.

DWORD WINAPI ThreadProc( LPVOID lpParameter )

{

HANDLE hWorkerThread = NULL;

DWORD dwProcessID = 0;

DWORD dwPrimaryThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwWorkerThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwCurrentThreadID = 0;

DWORD dwLandingArea = NULL;

DWORD dwExitAddress = NULL;

dwWorkerThreadID = GetCurrentThreadId();

...

}

With the mirrored frames in place, one can perform the previous test with certainty of the results:

if( GetCurrentThreadId() == dwWorkerThreadID )

{

asm ret

}

There is one caveat to using this method: the compiler does not reserve stack space in the order in which variables are declared. Figure 28 below demonstrates the warning. Notice that the variables are initialized in the order in which they were declared, but the RVAs are out of order: 0x12FF64, 0x12FF70, 0x12FF68.

Figure 28: Stack Layout of Variables

Figure 29 represents the executable under WinDbg. WinDbg shows relative based addressing, which fully demonstrates the issue. Again, variables are initialized as declared, but are not in the declared order on the thread's stack.

Figure 29: Stack Layout of Variables (Relative to EBP)

The compiler allocation issue means the programmer must be aware of allocation strategies, and verify the results under a debugger or a symbol tool.

Downloads

Acknowledgements

- Ken Johnson, Microsoft MVP

Revisions

- 11.14.2007 - Expanded PEB information.

- 11.07.2007 - Added Example 5.

- 11.01.2007 - Initial release.

References

- Microsoft website, Processes and Threads, accessed October 2007.

- J. Richter, Programming Applications for Microsoft Windows, 4ed., Microsoft Press, 1005, pp. 182-184, ISBN 1-5723-1996-8.

- M. Russinovich and D. Solomon, Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP and Windows 2000, Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 6, ISBN 0-7356-1917-4.

- M. Russinovich and D. Solomon, Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP and Windows 2000, Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 6, ISBN 0-7356-1917-4.

- J. Richter, Programming Applications for Microsoft Windows, 4ed., Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 69, ISBN 1-5723-1996-8.

- Microsoft website, About Processes and Threads, accessed October 2007.

- Microsoft website, Multiple Threads, October 2007.

- Microsoft website, About Processes and Threads, accessed October 2007.

- Microsoft website, How do I keep my driver from running out of kernel-mode stack?, accessed October 2007.

- Microsoft website, Fibers, accessed October 2007.

- M. Russinovich and D. Solomon, Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP and Windows 2000, Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 289, ISBN 0-7356-1917-4.

- Microsoft website,

PsLookupProcessByProcessId, accessed October 2007. - M. Russinovich and D. Solomon, Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP and Windows 2000, Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 289, ISBN 0-7356-1917-4.

- Microsoft website,

PsLookupThreadByThreadId, accessed October 2007. - Microsoft website, Environment Variables, accessed October 2007.

- M. Russinovich and D. Solomon, Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP and Windows 2000, Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 291, ISBN 0-7356-1917-4.

- Microsoft Website,

CreateThread Function, accessed Ocotber 2007. - M. Russinovich and D. Solomon, Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP and Windows 2000, Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 289, ISBN 0-7356-1917-4.

- J. Walton, An Analysis of the Windows PE Checksum Algorithm, accessed October 2007.

- M. Russinovich and D. Solomon, Microsoft Windows Internals, Fourth Edition: Windows Server 2003, Windows XP and Windows 2000, Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 12, ISBN 0-7356-1917-4.

- J. Richter, Programming Applications for Microsoft Windows, 4ed., Microsoft Press, 2005, p. 417, ISBN 1-5723-1996-8.