Introduction

Implementing multithreading in your applications is not always an easy task. For relatively simple solutions, the BackgroundWorker component present in the .NET Framework since version 2.0 provides a straightforward answer.

However, for more sophisticated asynchronous applications, Microsoft suggests implementing a class that adheres to the Event-based Asynchronous Pattern. This is cool, but still a little hard to do, and you need to repeat it all over again each time you need to run some stuff in a different thread.

I've done a few experiments myself with multithreading, starting with .NET version 1.1. Although I wouldn't call myself an expert on the subject, I'm sure of a few things:

- It's not easy

- It's hard to debug

- Organizations should not allow junior developers to start coding multithreaded applications without careful thinking and without the help of an experienced developer (one who knows about multithreading)

To help reduce these concerns, I've always wondered how I could make multithreading easier by somehow wrapping and handling some of its inherent complexity inside reusable base classes and helpers. This way, the developer would be able to concentrate less on the technical aspects coming with multithreading, and more on the features she/he wants to implement as multithreaded, and how they will interact with the main thread.

What I wanted my wrappers and manager classes to do was:

- Handle the creation of new threads

- Handle exceptions occurring in the created threads

- Easily switch between running the workers asynchronously and synchronously (first to see the impact on performance, and secondly to help debugging – although I agree it's not perfect)

- Handle inter-thread communication between parent and child threads (progression report, reporting results at the end of the worker thread, interruption requests, etc.)

With Generics and the use of the AsyncOperationManager and AsyncOperation classes, this has become really possible, and in my opinion, pretty clean.

Audience

In this article, I will not describe or explain the concepts behind threading, how they work, or how to use them. The article is not a reference guide to every possible aspect and technicality related to threading. So, it mostly targets developers and architects who are already aware of those details. You need to understand various threading principles, like locking mechanisms when sharing objects between threads and how to make these classes thread-safe, using threads to update the UI, etc.

If you would like to learn about those, there is a very good article written by Sacha Barber that introduces all of those concepts. You can find it here: Beginners Guide to Threading in .NET Part 1 of n.

Source Code and Demo

I have included the source code with this article, along with a demo project which uses three threads at the same time (plus the main UI thread), with the third thread being managed and started by the second one.

You can download the source code from the link above.

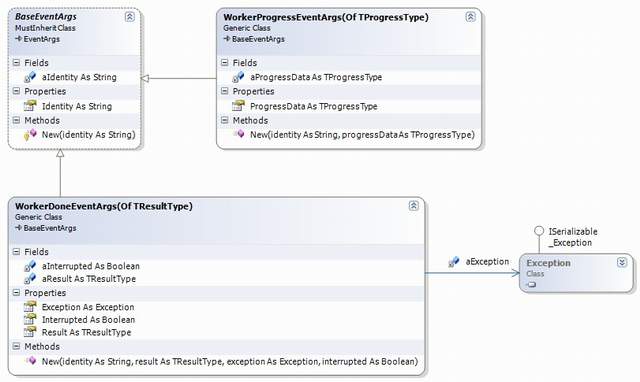

Class Diagrams

Here are the class diagrams for the wrapper/helper library.

Event Argument Classes

OK, let's look at the code now. First, I am publishing two different events from my manager, so let's review the event argument classes for them.

Namespace Events

#Region "Class BaseEventArgs"

Public MustInherit Class BaseEventArgs

Inherits System.EventArgs

Private aIdentity As String

Public ReadOnly Property Identity() As String

Get

Return aIdentity

End Get

End Property

Protected Sub New(ByVal identity As String)

aIdentity = identity

End Sub

End Class

#End Region

#Region "Class WorkerDoneEventArgs"

Public Class WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType)

Inherits BaseEventArgs

Private aResult As TResultType

Private aException As Exception

Private aInterrupted As Boolean

Public ReadOnly Property Result() As TResultType

Get

Return aResult

End Get

End Property

Public ReadOnly Property Exception() As Exception

Get

Return aException

End Get

End Property

Public ReadOnly Property Interrupted() As Boolean

Get

Return aInterrupted

End Get

End Property

Public Sub New(ByVal identity As String, _

ByVal result As TResultType, _

ByVal exception As Exception, _

ByVal interrupted As Boolean)

MyBase.New(identity)

If Not result Is Nothing Then

aResult = result

End If

If Not exception Is Nothing Then

aException = exception

End If

aInterrupted = interrupted

End Sub

End Class

#End Region

#Region "Class WorkerProgressEventArgs"

Public Class WorkerProgressEventArgs(Of TProgressType)

Inherits BaseEventArgs

Private aProgressData As TProgressType

Public ReadOnly Property ProgressData() As TProgressType

Get

Return aProgressData

End Get

End Property

Public Sub New(ByVal identity As String, _

ByVal progressData As TProgressType)

MyBase.New(identity)

If Not progressData Is Nothing Then

aProgressData = progressData

End If

End Sub

End Class

#End Region

End Namespace

You can see I have a base "must inherit" class (from which the other two inherit) that contains an Identity field that will be present in both the event argument classes. The identity exists so that you can identify the work being processed by your worker thread.

The WorkerDoneEventArgs class has a generic TResultType, which indicates the type of object used to store the results of a worker. The class also offers a member to store an exception that can occur in the worker, and a flag Interrupted to indicate if an interruption request was received by the worker.

The WorkerProgressEventArgs class has a generic TProgressType, which indicates the type of object used to store the progression data of a worker. This could be as simple as an Integer to only give a percentage of progression, or a full-blown custom class holding other information needed by the owner of the worker, between each progression step.

Worker Interface (IWorker)

Next, I need a simple interface to define the members of the base worker class, as seen by the manager, which will make use of them.

Namespace Worker

Public Interface IWorker

#Region "Properties"

Property AsyncManagerObject() As Object

ReadOnly Property InterruptionRequested() As Boolean

ReadOnly Property ResultObject() As Object

ReadOnly Property WorkerException() As Exception

#End Region

#Region "Subs and Functions"

Sub StartWorkerAsynchronous()

Sub StartWorkerSynchronous()

Sub StopWorker()

#End Region

End Interface

End Namespace

First, you see the AsyncManagerObject. It's there because the manager will need to give a handle to itself to the worker instance so that the worker can call its methods. Why is it declared as Object? Because at this stage, I don't know the types that will be used as generics to declare an instance of the manager. You will see later in the WorkerBase class how I transform this version of the AsyncManager from Object to its strongly-typed version.

The ResultObject is similar. Since I don't know the generics used to specify the type of object for the Result of the worker class, I have to declare it as Object.

The interface also contains the three very obvious methods to handle the starting and stopping of the worker.

The AsyncManager Class

Next, we go to the manager class, one of the most important in the solution.

Public Class AsyncManager(Of TProgressType, TResultType)

First, you see that the class uses two generic types. TProgressType specifies the type of object used to store the progression data (which relates to WorkerProgressEventArgs). TResultType specifies the type of object used to store the results of the worker (which relates to WorkerDoneEventArgs).

These generics are used throughout the manager code, to allow strong-typed signatures, preventing the consumer having to always cast every object required (which is also costly in terms of performance).

Public Sub New(ByVal identity As String, _

ByVal worker As Worker.IWorker)

aWorker = worker

aIdentity = identity

aWorker.AsyncManagerObject = Me

End Sub

The constructor receives a string used to uniquely identify the manager and worker, and the worker instance, declared as IWorker. You can see that the worker is given a handle to the manager, using the AsyncManagerObject property.

Public Event WorkerDone As EventHandler(Of Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType))

Public Event WorkerProgress As EventHandler_

(Of Events.WorkerProgressEventArgs(Of TProgressType))

Next, we see the event declarations. WorkerDone will be fired when the worker's process is finished, either normally, or after an exception has occurred, or after an interruption was received. The event arguments will allow distinction between the possible endings.

The WorkerProgress event will only be fired when the worker's code needs it.

Friend ReadOnly Property CallingThreadAsyncOp() As AsyncOperation

Get

Return aCallingThreadAsyncOp

End Get

End Property

Public ReadOnly Property Identity() As String

Get

Return aIdentity

End Get

End Property

Public ReadOnly Property IsWorkerBusy() As Boolean

Get

Return Not (aWorkerThread Is Nothing)

End Get

End Property

As for properties, notice CallingThreadAsyncOp() As AsyncOperation. This is the magical object that allows communication between the worker thread and the manager thread. This object gets created through System.ComponentModel.AsyncOperationManager, using its CreateOperation method. You will see a little further below how we use this object to execute methods on the manager thread.

The other important property is IsWorkerBusy, which indicates if the worker thread still exists, which means, in my design, that the worker is still busy doing its stuff.

Friend Overloads Sub WorkerProgressInternalSignal(ByVal state As Object)

WorkerProgressInternalSignal(DirectCast(state, TProgressType))

End Sub

Friend Overloads Sub WorkerExceptionInternalSignal(ByVal state As Object)

WorkerExceptionInternalSignal(DirectCast(state, Exception))

End Sub

Friend Overloads Sub WorkerDoneInternalSignal(ByVal state As Object)

WorkerDoneInternalSignal(DirectCast(state, TResultType))

End Sub

To be able to call methods on the manager's thread (the owner thread), we must use the Post method of the AsyncOperation object (through the CallingThreadAsyncOp member). The Post method requires a special kind of delegate that only accepts a State (as Object) as parameter. You will see a little further down, in the WorkerBase class, how we call the above SendOrPostCallBack methods. Notice that these methods only perform a call to the overloaded signature while casting the state object as its strong-typed version.

We will be signalling three different states from our WorkerBase to the manager: progression, exception, and regular ending.

Friend Overloads Sub WorkerProgressInternalSignal(ByVal progressData As TProgressType)

Dim e As Events.WorkerProgressEventArgs(Of TProgressType) = _

New Events.WorkerProgressEventArgs(Of TProgressType) _

(Identity, _

progressData)

RaiseEvent WorkerProgress(Me, e)

End Sub

Friend Overloads Sub WorkerExceptionInternalSignal(ByVal workerException As Exception)

If aIsAsynchonous AndAlso Not aWorkerThread Is Nothing Then

aWorkerThread.Join()

aWorkerThread = Nothing

End If

If Not aCancelWorkerDoneEvent Then

Dim e As Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType) = _

New Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType) _

(Identity, _

Nothing, _

workerException, _

aWorker.InterruptionRequested)

RaiseEvent WorkerDone(Me, e)

End If

If aIsAsynchonous Then

aCallingThreadAsyncOp.PostOperationCompleted(AddressOf DoNothing, Nothing)

End If

End Sub

Friend Overloads Sub WorkerDoneInternalSignal(ByVal result As TResultType)

If aIsAsynchonous AndAlso Not aWorkerThread Is Nothing Then

aWorkerThread.Join()

aWorkerThread = Nothing

End If

If Not aCancelWorkerDoneEvent Then

Dim e As Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType) = _

New Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType) _

(Identity, _

result, _

Nothing, _

aWorker.InterruptionRequested)

RaiseEvent WorkerDone(Me, e)

End If

If aIsAsynchonous Then

aCallingThreadAsyncOp.PostOperationCompleted(AddressOf DoNothing, Nothing)

End If

End Sub

Now, these are the overloaded methods of the SendOrPostCallBack versions. In asynchronous mode, the worker will be calling the SendOrPostCallBack version (with state as parameter) because it's required by the AsyncOperation.Post action, and in synchronous mode, the worker will be directly calling the overload, which accepts the strongly-typed version of the parameter.

The three methods take care of creating the specific event argument instance required and raise the event, so the owner of the manager instance, or any other object that subscribed to the events, receive notification. For the WorkerExceptionInternalSignal and WorkerDoneInternalSignal methods, the event raised is the same, but the arguments will contain different things. In the first case, Exception will not be null, but Result will. In the second case, Exception will be null, but Result shouldn't be. There is, however, another little catch.

You will see below that the manager has a function that is called by its owner to "wait" for the worker to complete (WaitForWorker). This function returns the same WorkerDoneEventArgs class as the "exception" and "done" signals above. In my design, I concluded that if the owner at some point wants to wait for the worker to complete, it should also process the result immediately after, in the same method it requested the wait. Therefore, I decided that the event itself should not be raised when the owner is waiting for the worker to end. This is what the field aCancelWorkerDoneEvent is used for.

Finally, when called asynchronously, these two "InternalSignal" methods also call PostOperationCompleted on the aCallingThreadAsyncOp (AsyncOperation) object. Notice that, right now, this in turn calls the private DoNothing method, which... does nothing. I'm not too sure if the PostOperationCompleted is absolutely required, but I decided not to take any chance and leave it there, but do nothing.

Let's go to the public methods now.

Public Sub StartWorker(ByVal asynchronous As Boolean)

aIsAsynchonous = asynchronous

aCancelWorkerDoneEvent = False

If aIsAsynchonous Then

aCallingThreadAsyncOp = AsyncOperationManager.CreateOperation(Nothing)

aWorkerThread = New Thread(New ThreadStart(AddressOf _

aWorker.StartWorkerAsynchronous))

aWorkerThread.Start()

Else

aWorker.StartWorkerSynchronous()

End If

End Sub

This is where we start the worker. You give this method a simple Boolean parameter to specify if you want to run in asynchronous (True) or synchronous (False) mode. If in asynchronous, the method takes care of creating the AsyncOperation through the AsyncOperationManager.CreateOperation service, creates the thread, and gives it the starting point StartWorkerAsynchronous from the worker interface aWorker, and starts the thread.

If in synchronous mode, it simply calls the StartWorkerSynchronous method from the same worker interface aWorker.

Public Sub StopWorker()

aWorker.StopWorker()

End Sub

This service simply calls its twin in the worker interface aWorker, to request it to stop.

Public Function WaitForWorker() As Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType)

If (Not aWorkerThread Is Nothing) AndAlso aWorkerThread.IsAlive Then

aWorkerThread.Join()

aWorkerThread = Nothing

End If

aCancelWorkerDoneEvent = True

Return New Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType) _

(Identity, _

DirectCast(aWorker.ResultObject, TResultType), _

aWorker.WorkerException, _

aWorker.InterruptionRequested)

End Function

As mentioned above, this service is used to wait for the worker to complete its job. When it does, it sets the flag aCancelWorkerDoneEvent to prevent the WorkerDone event from firing, and instead, directly returns the event arguments. Perhaps it's not the best design, since event arguments should probably only be used in events, but that's what I have to offer for now.

Public Function StopWorkerAndWait() As Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType)

Dim result As Events.WorkerDoneEventArgs(Of TResultType) = Nothing

If (Not aWorkerThread Is Nothing) AndAlso aWorkerThread.IsAlive Then

StopWorker()

result = WaitForWorker()

End If

Return result

End Function

Finally, the third service is a mix of the two above. It first requests the worker to stop, which is only a request sent and performed on the child thread, so after the call is done, execution continues in the manager and it doesn't mean the worker has processed the interruption request.

Therefore, it also waits for the worker to process the interruption request and complete, to be absolutely sure that the thread is left inactive.

The WorkerBase Class

That's it for the manager class. Now, to the last piece of my wrapper design, the abstract WorkerBase class.

Public MustInherit Class WorkerBase(Of TInputParamsType, _

TProgressType, TResultType)

Implements IWorker

First, you see the familiar generics we used in the manager and event argument classes above. This time, in addition to the TProgressType and TResultType, we also have a TInputParamsType, which defines the type of object used to hold the parameters required by the worker class.

Since this class is defined as MustInherit, it's in the declaration of the derived class that we will have to specify the generic types, like this:

Friend Class SubWorker1

Inherits SIGLR.Async.GenericWrapper.Worker.WorkerBase(Of SubWorker1Input, _

Integer, SubWorker1Result)

This specific worker class inherits from the WorkerBase class, with input parameters as SubWorker1Input, progress data as Integer, and results as SubWorker1Result.

Again, these generics are used throughout the base class, to allow strong-typed signatures, and to prevent the consumer from always having to cast every object.

Protected Sub New(ByVal inputParams As TInputParamsType)

aInputParams = inputParams

End Sub

The base constructor only requires the input parameters, of the type specified by the generic TInputParamsType. It will be passed to the DoWork method, which is MustOverride, and which contains the "real stuff" the worker will be running.

Friend Property AsyncManagerObject() As Object Implements IWorker.AsyncManagerObject

Get

Return aAsyncManagerObject

End Get

Set(ByVal value As Object)

aAsyncManagerObject = value

End Set

End Property

Protected Friend ReadOnly Property InterruptionRequested() As Boolean _

Implements IWorker.InterruptionRequested

Get

Return aInterruptionRequested

End Get

End Property

Friend ReadOnly Property ResultObject() As Object _

Implements IWorker.ResultObject

Get

Return aResult

End Get

End Property

Friend ReadOnly Property WorkerException() As Exception _

Implements IWorker.WorkerException

Get

Return aWorkerException

End Get

End Property

Since the base class implements the IWorker interface, these are the required properties. Nothing really special about them, apart from AsyncManagerObject and ResultObject, which I already talked about in the interface section above.

Protected MustOverride Function DoWork(ByVal inputParams _

As TInputParamsType) As TResultType

This is the DoWork method, which is MustOverride. It is given its parameters using the TInputTypeParamsType generic, and returns its result as an object of the generic type TResultType. Easy enough, don't you think?

This is where you need to be aware of how threads work. If there is any chance that objects used in this method may be shared by other threads (including the calling thread), these object classes should be made "thread-safe" with some locking mechanism. As mentioned in the Audience section of this article above, you may want to read Sacha Barber's article on threading to learn all of that.

Friend Sub StartWorkerAsynchronous() Implements IWorker.StartWorkerAsynchronous

aIsAsynchronous = True

aInterruptionRequested = False

aAsyncManagerTyped = DirectCast(aAsyncManagerObject, _

AsyncManager(Of TProgressType, TResultType))

aWorkerProgressInternalSignalCallback = New _

SendOrPostCallback(AddressOf aAsyncManagerTyped.WorkerProgressInternalSignal)

Dim workerDoneInternalSignalCallback As SendOrPostCallback = New _

SendOrPostCallback(AddressOf aAsyncManagerTyped.WorkerDoneInternalSignal)

Dim workerExceptionInternalSignalCallback As SendOrPostCallback = New _

SendOrPostCallback(AddressOf _

aAsyncManagerTyped.WorkerExceptionInternalSignal)

Try

aResult = DoWork(aInputParams)

aAsyncManagerTyped.CallingThreadAsyncOp.Post(_

workerDoneInternalSignalCallback, aResult)

Catch ex As Exception

aWorkerException = ex

aAsyncManagerTyped.CallingThreadAsyncOp.Post(_

workerExceptionInternalSignalCallback, aWorkerException)

End Try

End Sub

OK... This is the starting method for the new thread created by the manager. Notice how we cast the AsyncManager which was passed as object through the IWorker interface's AsyncManagerObject property. Now, it can be cast in its strong-type version AsyncManagerTyped because we know the generic types to use (they're the same as the ones used in the class declaration).

The method also defines the three required SendOrPostCallBack delegates, pointing to the AsyncManager's three methods that receive a state object. Notice that the progress method is declared as class global attributes while the other two are simply variables inside the method. This is because the progress delegate is required outside of this method, as you'll see further down.

Finally, the method calls the DoWork function. It is done inside a Try/Catch so that if an unhandled exception occurs, it will be able to call the workerExceptionInternalSignalCallback delegate with the exception as parameter. Otherwise, when the function returns, it will call the workerDoneInternalSignalCallback delegate with the result as parameter. Both delegates are called through the Post service of the manager's CallingThreadAsyncOp, to be executed on the manager's thread.

Friend Sub StartWorkerSynchronous() Implements IWorker.StartWorkerSynchronous

aIsAsynchronous = False

aInterruptionRequested = False

aAsyncManagerTyped = DirectCast(aAsyncManagerObject, _

AsyncManager(Of TProgressType, TResultType))

Try

aResult = DoWork(aInputParams)

aAsyncManagerTyped.WorkerDoneInternalSignal(aResult)

Catch ex As Exception

aWorkerException = ex

aAsyncManagerTyped.WorkerExceptionInternalSignal(aWorkerException)

End Try

End Sub

Although pretty similar to the asynchronous start worker method, this one is simpler and more straightforward, as it doesn't need any SendOrPostCallBack delegate because everything runs on the same thread.

Protected Sub WorkerProgressSignal(ByVal progressData As TProgressType)

If aIsAsynchronous Then

aAsyncManagerTyped.CallingThreadAsyncOp.Post(_

aWorkerProgressInternalSignalCallback, progressData)

Else

aAsyncManagerTyped.WorkerProgressInternalSignal(progressData)

End If

End Sub

This method's scope is Protected, as it will be called by the derived class to signal a progression of some kind. It receives progression data as TProgressType. If the worker is running in asynchronous mode, then the method uses the aWorkerProgressInternalSignalCallback SendOrPostCallBack delegate previously defined in the StartWorkerAsynchronous method. It does so through the Post service of the manager's CallingThreadAsyncOp, to execute the delegate method on the manager's thread.

If not in asynchronous mode, then it calls the manager's WorkerProgressInternalSignal method directly.

Friend Sub StopWorker() Implements IWorker.StopWorker

aInterruptionRequested = True

End Sub

This last method is called by its twin in the manager. It simply sets the aInterruptionRequested flag to True, so that the derived class can see the request and stop its work in a clean way.

How to Use the Wrapper / Manager

For each different functionality you want to run in a separate thread, you need to:

- Create a class which inherits from the

WorkerBase class and put your work's code in the DoWork method. - Optionally create a class to hold the input parameters required by the work you want done (which will become the

TInputParamsType generic). - Optionally create a class to hold the progression data you want to marshal between the worker and the calling thread at various stages in your work (might be in a loop too) (which will become the

TProgressType generic). - Optionally create a class to hold the results of the work, to be processed by the calling thread (which will become the

TResultType generic).

If you don't need one or more of the generic types (let's say you don't need any input parameters, or your work doesn't report progression, or doesn't return a result), you can use any other standard type (like Integer) as generics for the various declarations, it doesn't matter.

Then, from some point in your code where you want to start your parallel work, you use a new instance of the AsyncManager class, declared WithEvents to be able to handle the two possible events it will raise (WorkerDone and WorkerProgress), giving it a new instance of your worker class, and then call the manager's StartWorker method.

Put some code in the event handlers you care for and that's it, you're done! Sounds easy? Take a look at the demo project included in the source code attached to this article. If you have any questions about it, I'll be happy to answer.

Still, in the near future (depending on my spare time availability!), I will write a second article to follow-up on this one, explaining in details how to use the library.

Conclusion

Of course, there is still a lot of room for improvement. For example, right now, a single manager instance does not handle more than one thread at a time. If you call StartWorker repeatedly, you may get unexpected results.

You will probably see several other things that can be improved as well. To be honest, this is why I decided to post an article about it in the first time, so that I could benefit from the views and ideas of other experienced developers like you...

Version History

- 2014-05-22

- Created C# version of the demo

- 2009-04-22

- Updated the source code to include a C# version of the library, and also improve some of the code (fixing several Code Analysis warnings)

- Updated the code listings to the latest library version

- Added the Class Diagrams section

- Updated the How to Use the Wrapper/Manager section to announce a follow-up article to appear in the near future

- Added executable demo download

- Removed the Notice section

- 2009-04-18

- Added Audience section with link to Sacha Barber's introduction to threading article

- Added Version History section

- 2009-04-16