Introduction

As is the case in many disciplines (not just software design), the last thing to receive much attention is error handling, messaging, and user feedback. Usually, there are statements such as MessageBox(“You forgot to login”) spread throughout your code. As things progress, it is suddenly realized that many of these message and error-handling routines are duplicated, mismatched, or worst of all, no longer relevant to the difficulty that the user is experiencing. It then becomes quite burdensome to ferret out all these “messages” and ensure that they make sense, have no typos, and so on.

Further compounding the problem is where you may be faced with distributing an application in more than one language – formally known as localization. It is distracting at the very least and quite often humorous, to be using an application for, say English, and receive a message in Dutch.

If you have been involved in any project much beyond a simple “Hello World” example, you have no doubt experienced this. Fortunately, there are tools that provide a solution to the endless ‘MessageBox’ scenario.

At this point, some of you are no doubt saying to yourselves, “I know where this is leading”, and you are correct. That is, using the often overlooked message compiler and the Windows API function FormatMessage. However, there is one additional item that happens to be the subject of this article - an easy to use class that will retrieve and display messages.

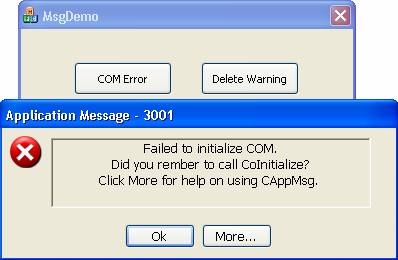

First, I should mention that AMX relates to the optional namespace declaration (optional via compiler directives). The class itself is called CAppMsg, and in addition to easing the task of extracting and formatting messages, it provides a dynamic dialog that is an enhancement over the standard dialog displayed by the API MessageBox function.

Before describing the CAppMsg class, though, a short description of the Microsoft message compiler is in order.

Message Compiler

There is a great deal of information available regarding message files and the use of Windows message compiler (mc.exe). Visual Studio’s online help is a good place to start. As such, I won’t go into all of the details of a message file layout. Suffice to say that a message file offers a single point of control for an application’s messages. This allows developers to coordinate and rely on an accepted standard for user information. As work progresses, the message bank (i.e., file) can be edited, recompiled (using the message compiler), and the resulting header, resource, and binary files distributed to all those concerned.

Additionally, message files can easily be configured to accept multiple languages, making localization much easier and less error prone than scrolling through megabytes of code looking for every “message box” instance.

To begin, a message file, which is simply a text file, is created (typically using the extension .mc) and includes a header section followed by message definitions. The header section defines Severity and Facility codes along with the language(s) that are targeted. The message section contains the definitions for the application’s messages. Each message is comprised of a MessageId, Severity, Facility, SymbolicName, and Language identifiers, along with the message content. Each message is delimited from the next by a single period (.) character. The following partial sample is taken from the Visual Studio documentation:

; // ***** Sample.mc *****

; // This is the header section.

MessageIdTypedef=DWORD

SeverityNames=(Success=0x0:STATUS_SEVERITY_SUCCESS

Informational=0x1:STATUS_SEVERITY_INFORMATIONAL

Warning=0x2:STATUS_SEVERITY_WARNING

Error=0x3:STATUS_SEVERITY_ERROR

)

FacilityNames=(System=0x0:FACILITY_SYSTEM

Runtime=0x2:FACILITY_RUNTIME

Stubs=0x3:FACILITY_STUBS

Io=0x4:FACILITY_IO_ERROR_CODE

)

LanguageNames=(English=0x409:MSG00409)

LanguageNames=(Japanese=0x411:MSG00411)

; // The following are message definitions.

MessageId=0x1

Severity=Error

Facility=Runtime

SymbolicName=MSG_BAD_COMMAND

Language=English

You have chosen an incorrect command.

.

Once a message file is defined, it is processed by the message compiler whose output, if successful, is a header (.h) and a resource (.rc) file by the same name as the message file. Along with these are one or more binary (.bin) files created using the naming convention of MSG00409.bin (English), MSG00411.bin (Japanese), etc. The binary file(s) contain the actual messages for each respective language. The syntax for using the message compiler is:

mc.exe AppMessages.mc

where AppMessages is the name of your specific message file. Once processed, the resultant files are incorporated into your own application. To do this, add a reference to the AppMessages.h header, typically in the application’s stdafx.h file.

#include <afxwin.h> // MFC core and standard components

#include <afxext.h> // MFC extensions

#include <afxdisp.h> // MFC Automation classes

#include <amx.h> // Support for AMX

#include <AppMessages.h> // Application’s message file header

The second requirement is to place a reference in your application to the generated resource file. This is usually done in the .rc2 file.

#ifdef APSTUDIO_INVOKED

#error this file is not editable by Microsoft Visual C++

#endif //APSTUDIO_INVOKED

#include "AppMessages.rc"

Again, the reader is directed to the Visual Studio documentation and other resources for a full discussion of message files.

Pre-Build Event

Rather than going to the effort of manually calling the message compiler each time the message file must be processed, a pre-build event can be added to your project. To do so, go to the application's properties dialog and make an entry as shown.

CAppMsg Class

After creating, compiling, and incorporating your messages, the Windows API function FormatMessage can be used to extract out any of the included messages. Using the FormatMessage function goes something like the following:

::FormatMessage(FORMAT_MESSAGE_ALLOCATE_BUFFER |

FORMAT_MESSAGE_FROM_HMODULE |

FORMAT_MESSAGE_ARGUMENT_ARRAY |

MAX_MESSAGE_LENGTH,

m_hInstance, dwMsgCode,

MAKELANGID(LANG_NEUTRAL, SUBLANG_DEFAULT),

(LPTSTR)&msgBuf,

0, &va_arg(lst, char*));

Kind of ugly, don’t you think! This, in my estimation, is why using a message box statement is more appealing, and an even greater reason to wrap such a function in a convenient class that can be as easy to use as a message box statement.

As you may have experienced, the reason for making a call to FormatMessage is to leave you with a formatted message string in the lpMsgBuf variable. This string is then used in a message box dialog. Oh wait! There’s that “message box” issue that we have been trying to get away from!

The objective then, is to have an object that could be dropped into place anywhere required with minimal hassle. That means, as little coding as possible and avoiding the exercise of defining or copying over a dialog resource for display purposes.

CAppMsg dynamically creates a dialog so no dialog resource definition is needed nor is there any reliance on MFC. All coding is straight C++ and system API calls. As such, the code should compile (with minimal changes) under any scenario with the exception of Visual Studio Express since the Standard Template Library (STL) is utilized.

CAppMsg can be instantiated using one of three constructors:

In addition to the constructors, there are two public methods and a global function used in exception handling.

BOOL ExtractMessage(DWORD dwMsgCode, ...)

dwMsgCode

The message identifier (symbolic name) from the header file produced by the message compiler.

- ellipses (

…)

The ellipses (…) argument is optional and allows additional string information to be formatted into the application message.

int ShowMessage(eDlgStyle eStyle = FD_OK, BOOL bMore = FALSE, HWND hParent = NULL)

eStyle

Defines the type of response buttons that will be displayed:

FD_OK

| OK button

|

FD_OKCANCEL

| OK and Cancel buttons

|

FD_YESNO

| Yes and No buttons

|

FD_YESALL

| Yes, No, and Yes to All buttons

|

bMore

Determines if the More… button will be displayed. This is primarily used for launching additional help information such as a compiled Windows Help file.

hParent

Handle of the parent window. Typically, NULL or this->m_hWnd.

void ThrowAppException(DWORD dwErrorCode, ...)

dwErrorCode

The message identifier (symbolic name) from the header file produced by the message compiler.

- ellipses (

…)

The ellipses (…) argument is optional and allows additional string information to be formatted into the application message.

It should be noted that CAppMsg defines a smart pointer that is used in exception handling. This eliminates the need (hence potential memory leaks) for remembering to delete the CAppMsg object. For example:

try

{

ThrowAppException(E_SOME_ERROR);

}

catch ( CAppMsgPtr pMsg )

{

pMsg->ShowMessage(FD_OK, TRUE));

}

To use AMX:

- Copy the amx.h and amx.cpp files to your project folder.

- Include the files in your project.

- Add a reference to amx.h, typically in the stdafx.h file.

- Create an instance of the

CAppMessage class. - Call

ShowMessage() to display.

CAppMsg and the included sample were written using Visual Studio 2005 and demonstrates several uses of the class.

Summary

By combining message files and the CAppMsg class, it is easy to manage all of the necessary messages and user feedback information that robust applications demand. With some up front planning and coordination, the “message box” quagmire can be avoided.

Also included with the demo project is a Windows Help file (AppMsg.chm) that can be used as a quick reference.

History

- July 20, 2009 - v1.0: Initial release.

- Aug 12, 2009 - v1.1: Fixed memory leak.