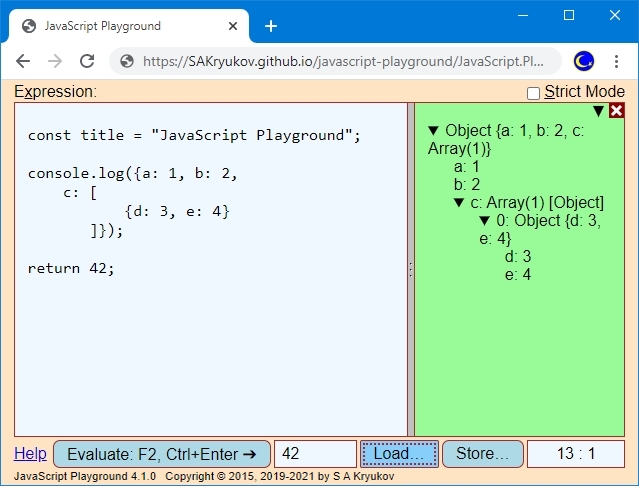

JavaScript Playground can be used as an advanced calculator. The result of the script execution can be viewed immediately; additionally, the console object can be used; structured console results can be browsed as it is done in the JavaScript IDE and debuggers. With playgroundAPI, it can be used as a tool for demonstration and teaching of JavaScript techniques.

Epigraph:

It is the child in man that is the source of his uniqueness and creativeness, and the playground is the optimal milieu for the unfolding of his capacities and talents.

- Eric Hoffer

Contents

Sentiments

JavaScript Playground as a Calculator

Core

User Script Context Protection

Host Context Protection

Console

File I/O

Exception Handling

Handling Lexical Errors

Protection from Losing Data

Playground API

Usage

Implementation

Limitations

Live Demo

Releases

Sentiments

JavaScript Playground is a fork of my very old tool, “JavaScript Calculator”. I’ve used it well before we got node.js and modern in-browser development tools, so I used it a bit for the development, but mostly as a calculator. My main drive was to get rid of any kinds of software calculators mimicking any historical devices, and any kinds of home-baked script parsers. It had to be based on an easy to use well-defined and standard language.

JavaScript Calculator became JavaScript Playground when I started to publish articles with JavaScript code samples and components. I decided that I can turn it into the compact self-containing tool used to demonstrate JavaScript code.

Later I added several useful things, such as file I/O and a fully-fledged console used to browse objects with complex structure.

JavaScript Playground as a Calculator

Core

This is the skeleton of the main script explaining the core functionality:

const consoleInstance =

const consoleApi =

const evaluate = () => {

const isStrictMode = strictModeSwitch.checked;

consoleInstance.reset();

try {

const api = {

write: (...objects) => consoleInstance.write(objects),

writeLine: (...objects) => consoleInstance.writeLine(objects),

consoleApi: consoleApi,

};

evaluateResult.value = evaluateWith(

editor.value,

api,

isStrictMode);

} catch (exception) {

consoleInstance.showException(exception);

} finally {

if (!isStrictMode)

hostApplicationContextCleanup();

}

};

const evaluateWith = (text, api, isStrict) => {

return new Function("api", safeInput(text, isStrict))(api);

};

const safeInput = (text, isStrict) => {

const safeGlobals =

"const write = api.write, writeLine = api.writeLine," +

"console = api.consoleApi, document = null," +

"window = null, navigator = null, globalThis = " +

"setReadonly({console: console, write: write, writeLine: writeLine})";

return isStrict ?

`"use strict"; ${safeGlobals}; ${text}`

:

`${safeGlobals}; with (Math) \{${text}\n\}`;

};On the very top stack frame of the script, the string with the user JavaScript code is obtained via editor.value and passed to evaluateWith with the api object used in the context of this code, and the flag, defining if this is a strict mode or not.

Note that the text of the user script is not passed to the instance of Function and executed directly. Some hidden part of code is added to the user script text. This part of the code is required to pass some API to the script. Additionally, the strict mode option and the shortcut feature with (Math) {} (only for non-strict mode) are passed.

The context of the code is defined in the function saveInput, and the first argument passed to the Function constructor matches the word “api” in the text of the code added by safeInput.

The result of the function call is returned and its value used to populate the control below the editor control evaluateResult;

The functions write and writeLine are implemented via consoleInstance, which is also used to implement consoleApi. They are added to keep backward compatibility with the predecessor project, JavaScript Calculator. The number of arguments they support is arbitrary. This is implemented using the spread syntax.

The object console re-implements the standard JavaScript console object. The actual argument passed as console by evaluate is the object with the console methods consoleApi.

In addition to passing the API to the user code, the code text added to the user script by safeInput protects the browser environment from unsafe calls and the user script from the modification of the API objects.

User Script Context Protection

Why safeInput is safe?

First of all, the text added by safeInput redefines global objects document, window, navigator as constants equal to null. This way, access to the sensitive environment properties is blocked. Also, globalWith needs some protection, and it takes some more effort.

It is important to protect the API provided to the user code from modification. Let’s consider possible troublesome pieces of the user code:

console.log(1);

console.log = null;

console.log(2);

console = null;

console.log(3);

or

globalThis.console.log(1);

globalThis.console.log = null;

globalThis.console.log(2);

globalThis.console = null;

globalThis.console.log(3);

What lines with the assignment to null can break the execution of console.log? What lines can cause trouble not only to the current execution of the user script but also to the entire JavaScript Playground session? Both kinds of trouble are possible if proper precautions are not taken. The same goes for write and writeLine. Any attempts to assign anything an API object should cause one of the two: the assignment should be ignored or throw an exception.

The first layer of protection is not using the functions of the api object directly, but via the separate constant objects write, writeLine and console. This way, a user’s attempt to assign a value to any of these objects will throw an exception. Note that JavaScript arguments are always mutable, but, thanks to this technique, the assignment like api = null cannot break anything, because it can only happen after the initialization of the API objects.

However, this alone won’t protect accessing these objects as globalThis.write, globalThis.writeLine or globalThis.console. It also won’t protect the console object from the modification of its function members, such as console.log or the same methods via, for example, globalThis.console.log. To prevent it, it is enough to make all the member functions of console and globalThis immutable.

This is the simplest method of making the properties of the object read-only based on Proxy:

const setReadonly = target => {

const readonlyHandler = { set(obj, prop, value) { return false; } };

return new Proxy(target, readonlyHandler);

};In this case, it is not recursive, only affects the properties of the object target. In JavaScript Playground, it is called with two objects: consoleApi and globalThis, prescribed in the form of the text of the user script, see evaluate and safeInput.

Host Context Protection

Having the user script context problem solved, we still have a problem presented by the non-strict mode. This mode is really nasty: when we create a top-level object, it is created in the global scope as a property of globalThis.

It contaminates the global scope of the host application. Yes, it happens even if the user script is executed by the Function constructor. To realize how bad it is, let’s consider the following simple example:

x = 10

Due to the strict mode, it is supposed to throw an exception “ReferenceError: x is not defined”. Will it happen? Not always. The answer depends on the prehistory of the entire JavaScript Playground session. Let’s do the following exercise: switch to the non-strict mode and execute:

x = 11

Then switch to the strict mode and execute

x = 12

y = 13

The assignment to x will work because in the strict mode the code will modify globalThis.x, defined in the global scope of the host application by the prior run of the user script in the non-strict mode.

Prior to version v. 4.2.0, the problem was solved by re-loading of the host application page via window.location.reload every time the “Strict Mode” control value was modified. It complicated things and became a big problem for the protection from losing data feature.

Since v. 4.2.0, the host application context is protected by registering the properties of globalThis before and after the execution of a user script in the non-strict mode. After the execution, the properties created by the user script are removed:

const hostApplicationContextCleanup = (() => {

const globalSet = new Set();

for (let property in globalThis)

globalSet.add(property);

return () => {

const currectSet = [];

for (let property in globalThis)

currectSet.push(property);

for (let property of currectSet)

if (!globalSet.has(property))

delete globalThis[property];

currectSet.splice(0);

};

})();Please see the use of hostApplicationContextCleanup in evaluate.

Console

The actual implementation of the object console passed to the safeInput function is consoleApi.

When an appropriate console method is called for the first time, a console element is created on the right of the editor control, taking some of its horizontal space of the window. The objects passed to this console method are visualized in the console. If the objects are structured, the appropriate tree structure is created. The nodes of the tree are created on the fly. It resolves the problem of circular references in the object.

Implemented console methods are console.assert, console.clear, console.count, console.debug, console.dir, console.error, console.info, console.log, console.time, console.timeEnd, console.timeLog, console.warn.

The only difference between console.debug, console.dir, console.error, console.info, console.log, and console.warn is the CSS style of a console message. For the objects derived from Object, these methods show interactive content in the console, representing a hierarchy of the object structure in the form of a tree. The nested levels of the hierarchy are shown when a tree node is open and removed when it is closed. This way, circular references in objects are allowed and represented safely. The second form of these functions, with the first argument representing a format string with substitution represented by the rest of the arguments, is not implemented, as it makes little sense. Instead, using template literals, introduced by ECMAScript 2015, is recommended.

The method console.assert(assertion, ...objects) also behaves like console.log and other similar methods, with the following exception: the first argument is boolean, reserved for the assert condition. If the first argument assertion evaluates to true, nothing happens, otherwise, the assertion failure message is displayed, followed by the rest of the arguments ...objects.

<uNote:

In some browsers, the timing methods console.time, console.timeEnd, console.timeLog may present accuracy problems. The time reading can be rounded or slightly randomized by a particular browser. At the moment of writing, correct timing was observed in Blink+V8-based browsers, such as Chromium, Chrome, Opera, and Vivaldi. Rounding was observed in the browsers using SpiderMonkey. For further information, please see this documentation page.

For the console implementation, see the function object consoleInstance.showException(exception) in the source code.

File I/O

File I/O is the newest feature. It is not very usual for a Web page, but there is nothing too difficult in it. File I/O is used in three points: 1) a JavaScript text can be loaden into the editor control, 2) the content of the editor control can be saved in a file, 3) the content of the console can be converted to text (possibly with some loss of information) and saved in a text file. This is the implementation:

const fileIO = {

storeFile: (fileName, content) > {

const link = document.createElement('a');

link.href = `data:text/plain;charset=utf-8,${content}`;

link.download = fileName;

link.click();

},

loadTextFile: (fileHandler, acceptFileTypes) > {

const input = document.createElement("input");

input.type = "file";

input.accept = acceptFileTypes;

input.value = null;

if (fileHandler)

input.onchange = event > {

const file = event.target.files[0];

if (!file) return;

const reader = new FileReader();

reader.readAsText(file);

reader.onload = readEvent >

fileHandler(file.name, readEvent.target.result);

};

input.click();

},

};Note that the modern File System Access API is not used here, even though it was used in the prototype project. The implementation based on the temporarily created elements and click call is simpler and sufficient for the purpose.

Exception Handling

In the code of evaluate, all exceptions are caught and handled by consoleInstance.showException(exception). If an exception is caught, the element corresponding to consoleInstance is shown with the yellow background and the exception information. At this point, there can be two cases: some browsers will locate the line and the column in the input script, the point where the error is detected, and report it. In some other browsers, this information is considered unsafe and is not available.

If this information is available, the text caret is also put in the reported position in the edit control. This is the skeleton of the consoleInstance member functions setting the caret and showing exception information:

const consoleInstance = {

setCaret: (line, column) => {

const lines = editor.value.split(definitionSet.textFeatures.newLine);

let position = 0;

for (let index = 0; index < line && index < lines.length; ++index)

position += lines[index].length + 1;

editor.setSelectionRange(position + column - 1, position + column);

},

showException: function (exceptionInstance) {

this.writeLine();

const knownPosition = isKnown(exceptionInstance.lineNumber)

&& isKnown(exceptionInstance.columnNumber);

if (knownPosition) {

this.writeLine(

[`Line: ${exceptionInstance.lineNumber - 2},` +

` column: ${exceptionInstance.columnNumber + 1}`]);

this.setCaret(

exceptionInstance.lineNumber - 3,

exceptionInstance.columnNumber + 1);

}

},

};Offsets in line and column numbers are explained by the fact, that not all script code is shown in the edit control. Some code is not visible, added by safeInput.

Handling Lexical Errors

It’s very typical that the script does not execute in the browser at all, silently, even if you use try to catch all exceptions. It happens when some errors are of the lexical level.

When you write regular JavaScript code without new Function, you cannot catch some errors on the lexical level.

You can catch:

try {

const x = 3;

x = x/y;

} catch (e) {

alert(e);

}but it would not work with

try {

const a = [1, 2, 3;]

} catch (e) {

alert(e);

}However, if you enter the second code fragment in the editor element, text area, pass its value to evaluate, and sandwich it a try-catch block, the lexical-level problem will be processed as an exception!

The code sample shown above will show the alert "SyntaxError: missing ] after element list".

You can consider this as a method of “converting all errors into exceptions”. All errors will be covered by common exception handling.

Protection from Losing Data

This feature is trivial, but I want to describe it, due to the abundance of recipes working or not working for different browsers. To the best of my knowledge, I put together the techniques to cover most browser peculiarities.

The user can easily unintentionally reload the page or remove it by closing its tab or window. If a user has some potentially valuable code in the code editor control, user confirmation is required. This is how to achieve it:

window.addEventListener('beforeunload', event => {

const requiresConfirmation = isCodeModified

&& editor.value.trim().length > 0;

if (requiresConfirmation) {

event.preventDefault();

event.returnValue = true;

} else

delete(event.returnValue);The status isCodeModified is updated by the input event of the code editor control:

editor.oninput = () => isCodeModified = true;

This status is cleared when the code is loaded from the file or supplied via the Playground API.

Not all lines of this code are absolutely required: deletion of event.returnValue could be replaced with the assignment to undefined, and event.preventDefault() might be redundant. However, there can be chances that in certain situations for certain browsers these lines will be essential. See this documentation page for more detail.

Playground API

The idea behind playgroundAPI is to pass some script to the main JavaScript Playground application “index.html”, populate the value of the editor control with the script text, and optionally execute it in the main application, optionally in strict mode. In this kind of usage, let’s consider the main JavaScript Playground application as a “host”, used by the “client” part written by the user.

This way, the user can run the client script in the context service application and do everything the application can do as a calculator. It can be done for the demonstration of the JavaScript code and technique, life demo illustrating publications, and so on. To see how it may look, please try out the Playground API Demo.

The user of playgroundAPI supplies the client script and instructs the host to populate edit control with the script text and define what to do with it. Naturally, it should be done in a very simple way. Let’s look at a simple code sample.

Usage

This is the simplest example of the client code using playgroundAPI:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<script src="../JavaScript.Playground/playgroundAPI.js"></script>

<script>

return "Write some code and press Ctrl+Enter"

</script>

<script>showSample("Just Calculator");</script>The host populates the editor control with the script text shown in the second scrip element and sets the Web page title to “Just Calculator”. By default, the host should execute the code and use non-strict mode. To change this behavior, the script should call showSample with one or two additional Boolean arguments. This call redirects to the how Web page, the host application, which does the rest.

Implementation

The core implementation object JavaScriptPlaygroundAPI implements functionality for both client and host parts. It also explains the idea:

const JavaScriptPlaygroundAPI = {

APIDataKey: "S. A. Kryukov JavaScript Playground API",

storage: sessionStorage,

userCall: function (path, code, title, doNotEvaluate, strict) {

this.storage.setItem(this.APIDataKey,

JSON.stringify({

code: code,

doNotEvaluate: doNotEvaluate,

strict: strict,

title: title }));

document.location = path;

},

onLoad: function (handler) {

const item = this.storage.getItem(this.APIDataKey);

this.storage.removeItem(this.APIDataKey);

if (!item) return;

const script = JSON.parse(item);

if (!script) return;

if (handler)

handler(script.title,

script.code,

script.doNotEvaluate,

script.strict);

},

};The method userCall provides the basic functionality of the client part. It initializes the operation. The function showSample should calculate the URL for the host Web page, the content of the second script element containing the text of the user script, define the options, and pass this data to userCall. This data is stored in the sessionStorage in the form of JSON.

To see how the data is collected from the user-supplied HTML by showSample, see its implementation in playgroundAPI.js.

After the user HTML to the host Web page, it is loaded and calls JavaScriptPlaygroundAPI.onLoad. If the content of sessionStorage is found by the key APIDataKey and evaluates to true, and the script text is not empty, JavaScriptPlaygroundAPI.onLoad calls the handler supplied by the host JavaScript Playground application. Depending on the options passed via JSON content, the host changes the page title, populates the editor element, optionally switched to the strict or non-strict mode, and optionally executes the user script code.

To find out the detail of the implementation of the host Web page behavior, please the fragments of the code by JavaScriptPlaygroundAPI. in “index.js”.

Limitations

Not all browsers can use sessionStorage after the relocation. It works with the modern browsers based on the Blink+V8 engines, but it could be a problem with some other browsers. In particular, Mozilla can do it only if the host application and the user HTML are located in the same directories.

To handle such situations, I decided to test some JavaScript features, to detect the browsers potentially not capable of supporting the use of playgroundAPI as it is presented in the demo code. At the time being, it can be detected by the support of the private class fields:

const goodJavaScriptEngine = (() => {

try {

const advanced = !!Function("class a{ #b; }");

return advanced;

} catch {

return false;

}

})();This solution is not perfect. What’s going to happen if some JavaScript engine like SpiderMonkey is upgraded with the support of the private class fields? Well, if the peculiarity with the Web page locations related to sessionStorage remains the same, something like Firefox will be able to use playgroundAPI and load the host JavaScript Playground Web page, but won’t populate the element editor with the script text.

Well, at least I warned and suggest what can be used in my error message. In the hide-and-seek game, the person who is “it” should call at the end of the time dedicated for hiding, before opening the eyes: “Ready or not, here I come!”. In its Russian form, the call is “If somebody is not yet hidden, this isn’t my fault”. Same thing here. :-)

Live Demo

JavaScript Playground application

Playground API Demo

Releases

4.0.0: Initial release after the fork from JavaScript Calculator

4.1.0: Introduced comprehensive user script context protection and protection from losing data.

4.2.0: Introduced host context protection, eliminated reloading of the host application on the modification of the “Strict Mode” control value.

4.3.0: Many fixes and improvements.