Introduction

The top scalable and modular approaches I covered in the previous

article in my CSS Architectures series all have pieces of brilliance that can

help you change the way you think about and structure your CSS. They also overlap

in many areas, which indicates which aspects of the process of improving your

CSS are truly critical. Although you could follow any single approach while constructing

a new site to great success, the fact of the matter is that what most of us are

doing is trying to make sense of existing CSS run amok.

So, while the approaches I described are great on their own,

what we really need is a way to combine the superpowers from them all to combat

the evil of crazy code – a sort of "Justice League" of scalable and

modular techniques. Furthermore, just as Rome wasn’t built in a day, it’s a

fool’s errand to try to correct in one fell swoop thousands of lines of code

that lack rhyme or reason. Thus, it’s a good idea to pass over the code in

focused waves through a phased approach.

Giving CSS Refactoring a Good Name

Last year, I had a project for a client where I was retained

to do exactly that. After studying DRY CSS, OOCSS, SMACSS, and CSSG, I

endeavored to distill them into their essential practices. In a moment of

insight, I realized that all these approaches boiled down to the well-known

adage "measure twice, cut once." Of course! They all encourage looking at

patterns, creating portable styles and modules that can be reused and not

adding superfluous and redundant selectors or styles.

Additionally, my client had a lot of code and wanted to have

flexibility in terms of the amount of changes that could be made to the CSS.

So, I developed a cohesive, phased plan of attack to reduce the number of lines

in my client’s CSS. By the end, all of the practices and techniques for all

four scalable CSS frameworks were incorporated, and the process I developed is

very effective at reducing lines of CSS.

Once I created the process, I had to figure out what to name

it. Taking "measure twice, cut once" as my base, I added CSS to it and this is

what I got:

measure twice, cut once css à

mtco css à meta coa css à MetaCoax!

So, in this article, I’ll share with you my MetaCoax CSS refactoring process, designed to

"de-bloatify" thousands of lines of redundant CSS—improving the readability,

simplicity and extensibility of the CSS while keeping the visible design and

functionality of the site the same. (Check

out the slides from my recent presentation on de-bloatifying CSS.)

To get yourself ready to refactor CSS, here are some

suggestions. First, be conversant with specificity and the cascade – it will make

a huge difference. I hope that in the first two articles in this series (Part 1, Part 2), I’ve

driven home that making selectors and rules overly specific limits their reusability.

When using descendent selectors especially, specificity can easily and quickly

spiral out of control, and that’s precisely what we’re working to avoid. Second,

remember inheritance rules: certain properties are inherited by child elements;

thus, how these properties cascade down the DOM should always be kept in mind.

The MetaCoax Process

The MetaCoax process is a four-phased approach. Each phase

builds on the previous one, and they all incorporate practices that decrease

the amount of code, increase scalability and maintainability and, as an added

bonus, lay the foundations for a future-friendly

site. We’ll look at a detailed breakdown of each phase and the practices and

techniques each encompasses. In this article, I’ll cover phases 1 and 2. Details

about phases 3 and 4 will appear in the final article in the series.

Note: An excellent tool to use while you’re going

through the MetaCoax refactoring process is Nicole Sullivan’s CSS Lint, which identifies additional places in

the CSS to clean up and gives you ideas on how to do so.

Phase 1: Shorten Selectors and Leverage and Layer Rulesets

The first phase is focused on a minimum amount of work to

improve a site’s CSS. These changes involve modifying the CSS but don’t touch

the current HTML for a site’s pages. The goal is to make the stylesheet a

little more lightweight and also easier to maintain and update with a small amount

of time and effort. The method involves optimizing selectors while reducing

redundancy with smarter reuse of rulesets. Even if you apply only the practices

from this phase to your CSS, you’ll see an improvement in maintainability.

Here's what we’re going to do:

- Shorten selectors chains

- Kill qualifiers

- Drop descendants

- Make the selector chain three or less

- Leverage and layer declarations

- Leverage the cascade by relying on inheritance

- Review, revise and reduce !important properties

- DRY ("don’t repeat yourself") your rulesets

Shorten Selector Chains

To best optimize selectors, the goal is to use a shallow instead of a deep

selector chain, making the chain as short as possible. This practice makes the code

easier to work with, and the styles become more portable. Other advantages are

reducing the chances of selector breakage, reducing location dependency,

decreasing specificity and avoiding specificity wars by preventing overuse of

!important declarations.

You have several ways in which you can shorten the selector chain,

incorporating practices from all of the scalable architectures I outlined and

further applying the "reduce, reuse, recycle" ethos. All of the practices are

guaranteed to make the CSS code more forgiving. And isn’t that essentially the

goal of updating our stylesheets?

Drop Descendent Selectors

The descendent selector (a b) is one of the most "expensive"

combinatory selectors to use to target an element. Other expensive CSS selectors

include the universal selector (*) and the child selector (a > b). What

makes them expensive? They are very general, and thus force the browser to look

through more page elements to make a match. The longer the selector chain and

the more checks required, the longer the browser takes to render the styles on

the screen. When matching a descendent selector, the browser must find every

instance of the key selector (which is the one on the far right) on the page,

and then go up the ancestor tree to make the match.

While this might not be a problem for a stylesheet of a few

hundred lines, it becomes more of an issue when the size of a document nears

10,000 lines or more. Even more important, in adopting a future-friendly and mobile first approach, long selector

chains create a situation where small, less capable devices are forced to load

and process unnecessarily large CSS documents.

Overdependence on descendent selectors is a vestige of the

days of coding for Internet Explorer 6, as Internet Explorer 6 did not render

the other CSS 2.1 combinator selectors at all. Because Internet Explorer 6 usage is now almost nonexistent in the United States and

other major markets, it’s completely safe to start employing selectors that are

compatible with Internet Explorer 7 and Internet Explorer 8 and let go of the

heavy use of descendent selectors once and for all. Table 1 shows the

selectors you can use with Internet Explorer 7. All versions of Internet

Explorer since then support all the selectors shown here.

| Selector | Internet Explorer 7 |

| Universal * | y |

| Child: e

> f

| y |

| Attribute:

e[attribute] | y |

| :first-child

| y |

| :hover | y |

| :active | y |

| Sibling/Adjacent:

e + f | n |

| :before | n |

| :after | n |

Table 1. CSS 2.1 Selectors Safe for Internet Explorer 7

Note: Check the charts at http://caniuse.com/ and http://www.findmebyip.com/litmus/ to

determine the browser support of other CSS selectors.

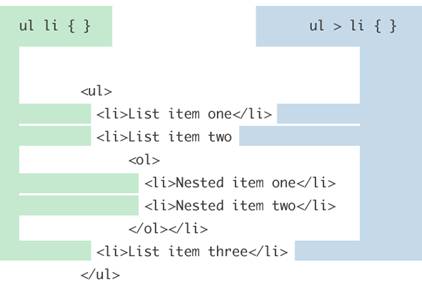

Instead of the descendent selector, use the child selector. The

child selector selects elements that are direct descendants of the parent

element—that is, direct children in the first generation—as opposed to a grandchild

or great-grandchild, which is what the descendent selector includes. Figure 1

illustrates this selection process.

Figure 1. A Descendent Selector vs. a Child

Selector

Although the child selector is still an "expensive"

selector, it is more specific. This means that the browser won’t search as far

down the inheritance chain to match the key selector. Thus, such a selector

targets the element you need much better.

If you must use a descendent selector, eliminate all superfluous

elements in it. For example:

.widget li a

would become

.widget a

The style will be applied whether the li is there or not.

Kill Qualified Selectors

Qualifying both #IDs and .classes with

elements causes the browser to slow unnecessarily to search for the additional

elements on the page to make a match with the selector. It is never necessary

to qualify an ID. An ID has one of the highest specificity weights in CSS

because it is unique to whatever page it is on, and it will always have a

direct match on its own. Qualified selectors also cause the specificity

of the selectors to be ridiculously high, necessitating the use of even more

specific selectors and the use of !important to trump these super-specific

rulesets.

Selectors such as

div#widget-nav div#widget-nav-slider

can be simplified to

#widget-nav

#widget-nav-slider

and further whittled down to

#widget-nav-slider

Each provides the same outcome.

Dropping an element class qualifier in

selectors lessens the specificity of the selector, which better enables you to

correctly use the cascade to override the style if necessary. For example,

li.chapter

would ideally be changed to

.chapter

Even better, because it is more specific to the case of the

<li>, you could consider changing the class on your <li> tag, and

scoping the CSS to

.li-chapter

or .list-chapter

Make It Three or Less

When working on optimizing selectors, institute a "three or

less" rule: a combinator selector should have no more than three steps to get

to the key selector. For example, take this doozy of a selector:

div#blog-footer div#col2.column

div.bestright p.besttitle {margin-bottom: 4px;}

To have three steps or less to get to the key selector, make

a change like this:

#col2.column .besttitle {border:

1px solid #eee;}

Leverage and Layer Declarations

The next order of business is to focus on the style

declarations themselves. When refactoring bloated CSS down to something more

manageable, it’s easy to focus primarily on the selectors and believe that the styles

will work themselves out. However, paying attention to what style declarations

you’re creating (see Figure 2) and where they go makes a difference as

well in moving toward sleek CSS.

Figure 2. Anatomy of a CSS Ruleset

Leverage Inheritance

Often, we think we know something really well when actually we

don’t, and inheritance in CSS may just be one of those areas. You might

remember that inheritance

is a fundamental concept of CSS, but you might not remember exactly which

properties naturally inherit and which do not. Table 2 shows the most

commonly used properties that get inherited by descendent elements, unless the

descendent elements are styled otherwise. (There are other more obscure

properties that are inherited as well.)

| color

font-family

font-family

font-size

font-style

font-variant

font-weight

font

letter-spacing

line-height

| list-style-image

list-style-position

list-style-type

list-style

text-align

text-indent

text-transform

visibility

white-space

word-spacing

|

Table 2. Common Elements Inherited by Descendent Elements

These properties are important to keep in mind when you’re looking

for redundant styles to consolidate or eliminate. When you’re updating the

stylesheet, properties that can be inherited should be placed in the CSS so

that they are best utilized and not repeated. With proper placement of these

properties, later redundant style declarations could be eliminated completely.

Review, Revise and Reduce !important Properties

If your CSS boasts an impressive number of !important

declarations, then it’s time to reduce it. You should really use !important declarations

only in certain instances. Chris Coyier of CSS

Tricks recommends using them with utility

classes or in user stylesheets. If you use them otherwise, you may end up

being branded as selfish

and lazy, and who wants that?!

How to cut down on !important? First, keep the specificity

of selectors low by following the suggestions I made earlier. Second, remember

that, ideally, new styles should not undo previous rulesets but add to them.

Here’s what I mean: if you find yourself writing new styles

to undo an earlier style (and then using !important to try to trump the style

in the event of a specificity war), then you need to rethink the older style,

distill it down to its necessities, and then create new styles that augment the

original style instead of working to undo what’s already there. This is what I

think of as "layering" style rulesets. This can also be referred to as

"extending" (or "subclassing") a style, which is part of creating modules in phase

2.

If you have a large number of !important properties for the

same styles, I bet those properties could be turned into a portable style that

could be applied to multiple elements, which I’ll also talk about when I

describe phase 2.

DRY Your Rulesets

To cut down on large numbers of repeated styles in the CSS,

a little DRY coding can help. While adopting the full DRY CSS approach may be a

bit draconian, being aware of when you repeat the same ruleset and then getting

your group on is

a great practice.

Phase 2: Restructure, Adjust, and Modularize

The techniques in phase 2 are focused on doing a moderate to

high level of work to improve a site’s CSS. The changes encompass altering both

the CSS and the HTML of the pages, with the changes to the HTML most likely to involve

renaming or reassigning class names. The goal is to give structure and

organization to the stylesheet, through grouping styles by category rather than

by pages, by removing archaic HTML, clearing the excess from the selectors and creating

modules to increase code efficiency.

This phase will further eliminate redundancy, make the

stylesheet more lightweight by improving selector accuracy and efficiency and

also aid in maintenance. This level of improvement takes more time and effort

than phase 1, but it includes the bulk of the work required to make your CSS

better and is estimated to dramatically cut down the number of lines of CSS

code.

Here is what we are going to do:

- Restructure to refactor

- Categorize CSS rules in the stylesheet

- Restructure styles that rely on qualifiers high in the DOM

- Use class names as key selector

- Begin instituting modules

- Extend module substyles with a double hyphen (--)

- Create portable helper styles

- Surgical layout helpers

- Typographical styles

- Adjust the HTML

- Eliminate inline styles

- Decrease use of <span> for better semantics

Restructure to Refactor

Let’s not forget that restructuring the CSS is our main

objective. These practices start the process of moving away from thinking about

and creating styles that are based on and specific to page components and page

hierarchy, and moving toward thinking of styles in a portable, reusable and

modular manner.

Categorize CSS Rules in the Stylesheet

In the first article

in this series, I suggested creating a table of contents to make finding the

sections of the styles in your CSS easier. In this phase of CSS refactoring, I

recommend stepping up that process several notches by transforming these sections

to the types of styles they describe, following the SMACSS categories.

These categories are:

- Base The default styles, usually single element

selectors that will cascade through the whole document.

- Layout The styles of the page sections.

- Module The reusable styles of the various modules of

the site: callouts, sidebar sections, product, media, slideshows, lists, and so

on.

- State The styles that describe how a module or

layout looks in a particular state.

- Theme The styles that describe how modules or

layouts might look.

So now, your table of contents and document sections will

look like this:

…

(later in the document…)

(etc.)

This reorganization of the stylesheet helps lay the

foundation for the rest of the phase 2 practices and is a part of phase 3 as

well.

Restructure Styles That Rely on Qualifiers High in the DOM

This recommendation is one of most important in this whole

article: to completely eliminate page specific styles—that is, styles that are

based on adding a class to the body element to signify a different page. A

style such as this forces the browser to check all the way up the DOM chain to

the <body> tag. Here’s an example:

body.donations.events

div#footer-columns div#col1 div.staff span.slug {

display: block;

margin: 3px 0 0 0;

}

This practice is the root of long selector chains,

super-high specificity of selectors and the need to use !important to override

styles higher up the cascade, as in the following example:

body.video div#lowercontent

div.children.videoitem.hover a.title { background: #bc5b29;

color: #fff !important;

text-decoration: none;

}

In other words, it’s bad. Mmkaay?

To fix it, you need to follow all of the previous

suggestions, such as three or less, kill the qualifiers and reduce specificity.

What you could end up with is something more like this:

.donations-slug {

display: block;

margin: 3px 0 0 0;

}

Use Class Names as Key Selector

Because IDs are highly specific, you should avoid using them

whenever possible, as they cannot be reused as classes can. However, in

creating classes you want to keep your class names semantic yet portable. The goal

is to make a selector as direct as possible. By doing this, you avoid

specificity problems and can then even combine styles to layer them as

suggested earlier.

From SMACSS, you should instill the practice that when you create

selectors, the key selector should be a .class instead of a tag name or an #id.

Always keep in mind that the far-right key selector is the most important one.

If a selector can be as specific to the element in question as possible, then

you’ve hit the jackpot. This way, the styles are targeted more directly because

the browser matches only the exact elements.

Review all places where child selectors are used, and

replace them with specific classes when possible. This also avoids having the

key selector in the child combinator as an element, which is also discouraged.

For example, instead of doing this:

#toc > LI > A

it’s better to create a class, as shown next, and then add

it to the appropriate elements.

.toc-anchor

Nothing epitomizes the "measure twice, cut once" adage in

the scalable CSS approaches as well as modules, which are the heart and soul of

all of them. Modules are components of code that can be abstracted from the

design patterns—for example, frequent instances of lists of items with images that

float either to the left or right or underneath; these can be abstracted into a

module with a base set of styles that every module would share. Then the module

can be extended (or skinned) with changes in text, background, font color,

borders, floats, and so on, but the structure remains the same.

The best thing about modules is that they are portable,

meaning that they are not location dependent. Abstracting a design pattern into

a code module means that you can put in anywhere in any page and it will show

up the same way, without you having to reinvent the wheel style-wise. Now that’s

what CSS was made for, right?! In addition to my earlier suggestions,

modularizing your CSS is one of the best ways to dramatically decrease the

amount of code.

OOCSS provides a great way to think about how to structure and skin a module and also about what can be made into a

module. SMACSS provides clear

guidelines on how to name modules and extend them.

Extend Substyles with --

Although SMACSS gives great guidance for thinking about extending

modules, I prefer the technique from CSS for Grownups of extending substyles

with --. This makes a lot of sense to me because it is a visual indication that

the new style is based on the previous one but is taking it further.

Here’s an example:

#go, #pmgo{

width: 29px;

height: 29px;

margin: 4px 0 0 4px;

padding: 0;

border: 0;

font-size: 0;

display: block;

line-height: 0;

text-indent: -9999px !important;

background: transparent url("/images/go.jpg") 0 0

no-repeat;

cursor: pointer;

x-cursor: hand;

}

#pmgo{

margin: 2px 0 0 3px;

background: transparent url("/images/go.jpg")

no-repeat center top;

}

This code could be modified and changed into something more

like this:

.button-search{

width: 29px;

height: 29px;

margin: 4px 0 0 4px;

padding: 0;

border: 0;

font-size: 0;

display: block;

line-height: 0;

text-indent: -9999px !important;

background: transparent url("/images/go.jpg") 0 0

no-repeat;

cursor: pointer;

x-cursor: hand;

}

.button-search--pm{

margin: 2px 0 0 3px;

background: transparent url("/images/go.jpg")

no-repeat center top;

}

Create Portable Helper Styles

Along with the process of modularization, portable styles

are another handy tool to have in your arsenal. Here are some examples from CSS

for Grownups.

Surgical Layout Helpers

By CSS for Grownups’ standards, there’s no shame in having a

little extra layout help. While a grid takes care of a lot of issues, these

styles may give elements a little nudge when needed (especially in terms of

vertical spacing), while eliminating lines of code.

.margin-top {margin-top:

5px;}

.margin-bottom

{margin-bottom: .5em;}

Although in most cases we strive to keep names semantic when

creating classes, in this instance descriptive names are fine.

Typographical Styles

Typographical styles are perfect if you find that much of

your CSS is devoted to changing the font face, size and/or line height. Both OOCSS

and CSS for Grownups suggest dedicated typographical styles that are not tied

to the element, such as the following:

.h-slug {font-size: .8em;}

.h-title {font-size: 1.5em;}

.h-author {font-size: 1em;}

A great exercise is to search for the properties font,

font-size, font-face, and h1 through h6 and marvel at the sheer magnitude of

the instances of these properties. Once you’ve had a good laugh, figure out

which styles apply to what, which sizes are important, and then start making

some portable typographical styles.

Adjust the HTML

While the practices in phases 1 and 2 that we’ve covered so

far offer miracles in terms of CSS cleanup, we can’t forget about the page

markup. Most likely, as suggested by Andy Hume in CSS for Grownups, you’ll need

to make changes to the HTML beyond adding new class names.

Decrease Use of <span> for Better Semantics

Do you have a rampant use of the <span> tag where a more

semantic tag would be much more appropriate? Remember, the <span> tag is

really for inline elements, not block-level elements, as stated by the W3C (http://www.w3.org/TR/html401/struct/global.html#h-7.5.4), so using <span> for headers and other

elements intended to be block-level is technically incorrect.

Here, for example, the spans should really be paragraphs or

header tags that indicate where this content fits in the document’s hierarchy.

Either of those other elements could have provided a base for the class hooks.

<li

class="item">

<a href="http://www.codeproject.com/learning/hillman"

title="">

<img src="http://www.codeproject.com/images/brenda-hillman.jpg"

alt="Air in the Epic" />

</a>

<span

class="slug">Brenda Hillman Essays</span>

<span

class="title"><a href="http://www.codeproject.com/learning/hillman"

title="Air in the Epic" class="title">Air in the Epic</a></span>

<span

class="author">Brenda Hillman</span>

</li>

The following version of this code would be an improvement

from a semantics standpoint:

<li

class="item">

<a href="http://www.codeproject.com/learning/hillman"

title="">

<img src="http://www.codeproject.com/images/brenda-hillman.jpg"

alt="Air in the Epic" />

</a>

<p

class="slug">Brenda Hillman Essays </p>

<h3

class="title"><a href="http://www.codeproject.com/learning/hillman"

title="Air in the Epic" class="title">Air in the Epic</a></h3>

<p

class="author">Brenda Hillman</p>

</li>

Eliminate Inline Styles

Finally, you need to get rid of inline styles. In this day

and age, inline styles should rarely if ever be used. They are much too closely

tied to the HTML and are akin to the

days of yore when <font> tags were running rampant. If you use inline

styles to override specificity, then making the changes suggested in this

article should already help you avoid specificity wars, effectively eliminating

the need for inline styles.

For example, this inline style:

<span

class="text-indent: 1em">Skittles are tasty</span>

could easily be turned into its own class that can be applied

throughout the document, like so:

.indent {text-indent: 1em:}

Your mission, should

you choose to accept it, is to find all the instances of inline styles and

see where you can make those styles portable helpers. The property you’re using

could easily be made into a portable style that can be reused on the other

instances of text.

Try It, It Will Be Good for You!

At the Øredev Web development

conference in Malmö, Sweden, I had the pleasure of seeing the brilliant Katrina Owen present "Therapeutic Refactoring." She suggested that when faced with a deadline, she

turns to refactoring horrible code to help her gain a sense of control and

rightness in the world.

You can approach restructuring your CSS for the better the

same way. By healing what ails your CSS, you can gain a sense of calm and

power, while beginning to make the world of your site’s stylesheets a better

place, one line of code at a time.

Stick with me, though, because we aren’t quite finished. We

have two more phases to cover in the MetaCoax process that will fully oust the

evil from your CSS once and for all, and will also enable you to leave a legacy

of goodness behind for all of the front-end devs that come after you.

This article is part of the

HTML5 tech series from the Internet Explorer team. Try-out the concepts in this article with three months of free

BrowserStack cross-browser testing @http://modern.IE

Links for Further Reading

This article was written by Denise R. Jacobs. Denise is a well-regarded expert in Web

design and is an industry veteran with more than 14 years of experience. She is

now doing what she likes best: being a Speaker + Author + Web Design Consultant + Creativity Evangelist. Most appreciated on Twitter as @denisejacobs for her "great

resources," Denise is the author of The

CSS Detective Guide, the premier book on troubleshooting CSS code, and

coauthor of Interact with Web

Standards and Smashing Book #3:

Redesign the Web. Her latest pet project is to encourage more people

from underrepresented groups to Rawk the Web

by becoming visible Web experts. You can reach her at denise@denisejacobs.com and see more

at DeniseJacobs.com.