Introduction

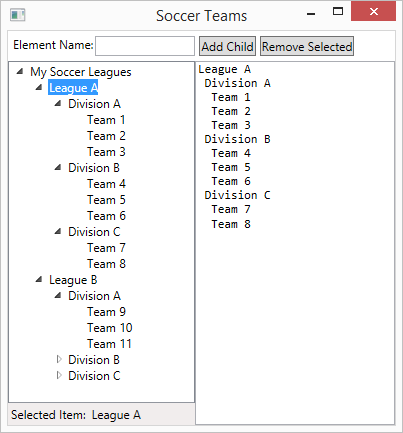

In this tip, I will describe a basic Tree structure based on ObservableCollection, where each element may contain child elements of a same type. The number of nested levels is unlimited. This type of collection may become handy if you need to store or manipulate hierarchical data. Since collections are internally based on ObservableCollection class, the tree fits very well for WPF binding scenarios. For example, in the attached sample project, I used it to display data in the TreeView using HierarchicalDataTemplate. Any modification of original object graph gets reflected in the UI automatically, thanks to WPF Data Binding.

Another important aspect of this particular implementation of Tree is that my goal was to make the code as compact as possible and rely on the original implementation of ObservableCollection as much as possible. As result, all manipulations with tree, like adding, removing, replacing nodes, etc. are supposed to be performed using well-known methods and properties of standard IList<T>.

Interface

The Tree class implements the following interfaces:

public interface ITree

{

bool HasItems { get; }

void Add(object data);

}

public interface ITree<T> : ITree, IEnumerable<ITree<T>>

{

T Data { get; }

IList<ITree<T>> Items { get; }

ITree<T> Parent { get; }

IEnumerable<ITree<T>> GetParents(bool includingThis);

IEnumerable<ITree<T>> GetChildren(bool includingThis);

}

ITree is non-generic base interface. The generic interface ITree<T> overrides ITree and exposes additional properties and methods that involve generic type. The reason of splitting the interface to non-generic and generic is to be able to easily identify instances compatible with ITree elements in the Add method.

Note that ITree<T> is also derived from IEnumerable<ITree<T>>. This is an indication that any element of the tree may have its own children. So you can easily iterate over a tree element without having to worry about presence or absence of children in it. It also provides syntactical sugar while using Linq or foreach constructs.

Below are methods and properties of ITree<T>:

- ?

HasItems - returns true if the tree node contains any child elements. Add - adds object(s) to children collection. Note that the method accepts object type as an argument. This is to support scenarios where you can add multiple objects at the same time. I will demonstrate this later.Data - returns generic data object associated with current node.Items - exposes a collection of child elements as IList<T>. You can use this property to add, remove, replace, reset children.GetParents() - a method enumerating all parent nodes, if any. Optionally may include itself in the result.GetChildren() - a method enumerating all child nodes, if any. Optionally may include itself in the result.

Implementation

The Tree class implements the ITree and ITree<T> interfaces described above. In the constructor, you can pass a generic Data object as well as optional child nodes. When child nodes are passed, they are added using the following Add method:

public void Add(object data)

{

if (data == null)

return;

if (data is T)

{

Items.Add(CloneNode(new Tree<T>((T) data)));

return;

}

var t = data as ITree<T>;

if (t != null)

{

Items.Add(CloneTree(t));

return;

}

var o = data as object[];

if (o != null)

{

foreach (var obj in o)

Add(obj);

return;

}

var e = data as IEnumerable;

if (e != null && !(data is ITree))

{

foreach (var obj in e)

Add(obj);

return;

}

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot add unknown content type.");

}

As you can see, every child element gets cloned before adding to collection. This is necessary to avoid circular references that may lead to unpredictable behavior. As result, if you want to override the Tree class with your own version (for example, you may want to create a class that hides generic type like: class PersonTree : Tree<Person>), you would have to override virtual CloneNode method returning appropriate instance of your type.

Another aspect of Add method is that it can digest any type of IEnumerable or its derivatives as long as their elements are of type ITree<T> or simply T. Here is an example of ITree<string> constructed using various methods:

var tree = Tree.Create("My Soccer Leagues",

Tree.Create("League A",

Tree.Create("Division A",

"Team 1",

"Team 2",

"Team 3"),

Tree.Create("Division B", new List<string> {

"Team 4",

"Team 5",

"Team 6"}),

Tree.Create("Division C", new List<ITree<string>> {

Tree.Create("Team 7"),

Tree.Create("Team 8")})),

Tree.Create("League B",

Tree.Create("Division A",

new Tree<string>("Team 9"),

new Tree<string>("Team 10"),

new Tree<string>("Team 11")),

Tree.Create("Division B",

Tree.Create("Team 12"),

Tree.Create("Team 13"),

Tree.Create("Team 14"))));

Finally, the implementation of Parent property. This property is essential to any hierarchical data structure because it allows you to walk up the tree providing access to the root nodes. By default, the Items collection of a node is not initialized (m_items = null). Once you try to access Items property or add an element to it, the instance of ObservableCollection is created as container for child nodes. The ObservableCollection's CollectionChanged? event is internally hooked to a handler that assigns or unassigns the Parent property of the children being added or removed. Here is how the code looks:

public IList<ITree<T>> Items

{

get

{

if (m_items == null)

{

m_items = new ObservableCollection<ITree<T>>();

m_items.CollectionChanged += ItemsOnCollectionChanged;

}

return m_items;

}

}

private void ItemsOnCollectionChanged(object sender, NotifyCollectionChangedEventArgs args)

{

if (args.Action == NotifyCollectionChangedAction.Add && args.NewItems != null)

{

foreach (var item in args.NewItems.Cast<Tree<T>>())

{

item.Parent = this;

}

}

else if (args.Action != NotifyCollectionChangedAction.Move && args.OldItems != null)

{

foreach (var item in args.OldItems.Cast<Tree<T>>())

{

item.Parent = null;

item.ResetOnCollectionChangedEvent();

}

}

}

private void ResetOnCollectionChangedEvent()

{

if (m_items != null)

m_items.CollectionChanged -= ItemsOnCollectionChanged;

}

Helper Tree Class

The helper static Tree class provides syntactical sugar for creating tree nodes. For example, instead of writing:

var tree = new Tree<Person>(new Person("Root"),

new Tree<Person>(new Person("Child #1")),

new Tree<Person>(new Person("Child #2")),

new Tree<Person>(new Person("Child #3")));

You could express the same code in a slightly cleaner way:

var tree = Tree.Create(new Person("Root"),

Tree.Create(new Person("Child #1")),

Tree.Create(new Person("Child #2")),

Tree.Create(new Person("Child #3")));

Also, there is a helper Visit method. It takes a tree node ITree<T> and an Action<ITree<T>> recursively traversing the tree node and calling the action for each node:

public static void Visit<T>(ITree<T> tree, Action<ITree<T>> action)

{

action(tree);

if (tree.HasItems)

foreach (var item in tree)

Visit(item, action);

}

For example, you can use this method to print a tree:

public static string DumpElement(ITree<string> element)

{

var sb = new StringBuilder();

var offset = element.GetParents(false).Count();

Tree.Visit(element, x =>

{

sb.Append(new string(' ', x.GetParents(false).Count() - offset));

sb.AppendLine(x.ToString());

});

return sb.ToString();

}

Summary

The Tree<T> collection is a simple hierarchical data structure with the following features:

- Supports generic data types

- Automatically maintains a reference to

Parent node - Friendly to WPF binding

- Fluid syntax of constructing and accessing elements

- Utilizes standard .NET

IList<T> features and functionality