Contents

Overview

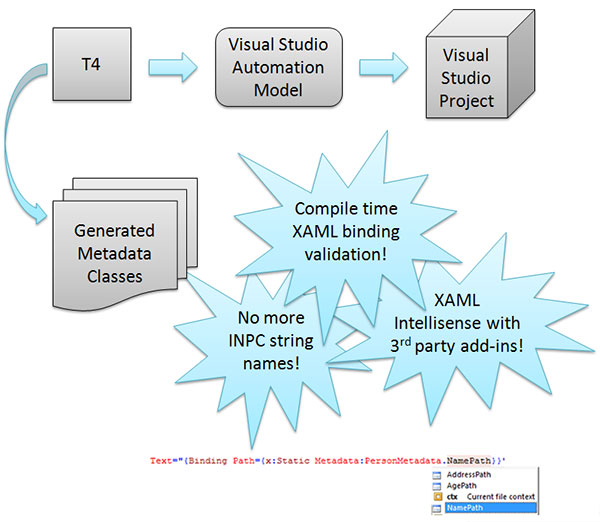

Have you ever wished that you could bind properties to your WPF controls without using string literals

to identify property names? This article describes how to use the T4 (Text Template Transformation Toolkit), which is built into Visual Studio 2008,

and the Visual Studio automation object model API, to generate member and type information for an entire project. Generated metadata

can then be applied to such things as dispensing with string literals in XAML binding expressions

and overcoming the INotifyPropertyChanged property name string code smell,

or indeed any place you need to refer to a property, method, or field by its string name. There is

also experimental support for obfuscation, so member names can be retrieved correctly even after obfuscation.

I've also ported the template to VB.NET, so our VB friends can join in on the action too.

Introduction

I've been spending a lot of time lately on my latest series of Calcium articles (I am in the process of porting Calcium to Silverlight), but this week I confess that I got a little sidetracked. I have discovered the joys of generating code with T4, and I have used it to build a metadata generator for your Silverlight and Desktop CLR projects (C# and VB.NET). It can be used as a replacement for static reflection (expression trees), reflection (walking the stack), and various other means for deriving the name of a property, method, or field. It can also be used, as I will demonstrate, to replace those nasty string literals in XAML path binding expressions, with statically typed properties; allowing the detection of erroneous binding expressions at compile time rather than at runtime.

Let us begin by looking at an example. In the following excerpt we see how a simple binding is traditionally expressed in WPF XAML:

Example 1 (traditional)

<StackPanel DataContext="{Binding Source={StaticResource Person}}">

<TextBlock >Name:</TextBlock>

<TextBox Text="{Binding Name}" />

</StackPanel>

Binding errors can be hard to spot, and time consuming to diagnose. The downside of using string literals, as shown in the example above, is that if the Binding Path property expressed as Name is incorrect, then we will learn of it only at runtime. Ordinarily, diagnosis of binding errors is done at runtime using one or more of the following four available techniques:

- Watching Visual Studio’s Output window for errors.

- Adding a breakpoint to a Converter.

- Using Trace Sources.

- Using the property PresentationTraceSources.TraceLevel.

But by generating metadata, we have the opportunity to express the same binding using a statically typed property:

Example 2 (using the MetadataGeneration template)

<StackPanel DataContext="{Binding Source={StaticResource Person}}">

<TextBlock >Name:</TextBlock>

<TextBox Text="{Binding Path={x:Static Metadata:PersonMetadata.NamePath}}"/>

</StackPanel>

The difference between the two examples is profound. In the second example, if the name of the property is incorrect, a compile time error will occur. Thus saving time and perhaps, in some cases, a little piece of sanity.

We can also use the generated metadata for removing the INotifyPropertyChanged string name code smell. I will demonstrate how in a moment, but first I want to briefly provide you with an overview of what’s happening behind the scenes.

Behind the Scenes

Introducing T4

T4 (Text Template Transformation Toolkit) is a code generation system that is available

in Visual Studio 2008 and 2010 out of the box (apart from Express edition). The format of T4 templates resembles that of ASP.NET, where tags are used to segregate various parts.

It’s easy to create a template. Simply add a new text file to a project within Visual Studio, and change its file extension to .tt.

Figure: Screenshot of Visual Studio Add New Item.

After a template is created, there is an associated .cs file. This is the destination for the generated output of our template.

Figure: Template file and associated C# output file.

There are some differences in the way that Visual Studio treats templates in VB.NET and C# projects. When using VB.NET note that an associated .vb file will not be created until an output directive is added to the top of the template like so:

<#@ output extension=".vb" #>

Also, to view the generated output for a VB.NET template, select ‘Show All Files’ in the Solution Explorer.

Figure: VB.NET T4 template

To see the T4 system in action, add the following text to the newly added .tt file:

C#:

public class SimpleClass

{

<# for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

{ #>

public int Property<#= i #> { get; set; }

<#

} #>

}

VB.NET:

<#@ output extension=".vb" #>

<#@ template language="VBv3.5" #>

public Class SimpleClass

<#

Dim i As Integer

For i = 1 to 3 #>

Dim field<#= i #> As Integer

<# Next #>

End Class

At the time of writing, T4 templates in Visual Studio 2008 default to C# 2.0, so we see that even in a VB.NET project we need to override the setting.

There are a number of ways to have Visual Studio process the template and generate output. We can save the template, right click on the file and select the Run Custom Tool context menu item, or use the Solution Explorer button shown in the following image.

Figure: Transform all templates by using a button in the Solution Explorer.

Initiating the template generation will cause the associated output file to be populated with the following content:

C#:

public class SimpleClass

{

public int Property0 { get; set; }

public int Property1 { get; set; }

public int Property2 { get; set; }

}

VB.NET:

public Class SimpleClass

Dim field1 As Integer

Dim field2 As Integer

Dim field3 As Integer

End Class

In order to create something of a little more use, it is necessary to understand the various T4 tag types.

My fellow Disciple Colin Eberhardt

has a great primer on T4 in the article Generate WPF and Silverlight Dependency Properties using T4 Templates. If you are new to T4, I recommend reading it to deepen your understanding of T4. In it Colin provides an overview of the various block types, and how to use T4 with Silverlight; topics I will not be covering here.

Exploring a Visual Studio project programmatically

In order to generate metadata from a Visual Studio project we make use of a single template to traverse the project structure, and then output classes with static properties (or constants where XAML support is not required) representing class member names, and PropertyPaths for use in XAML binding expressions. To accomplish this we could resort to using reflection and AppDomains, but that would be slow and fraught with peril. Fortunately we are able to harness the Visual Studio EnvDTE.DTE instance (the top-level object in the Visual Studio automation object model), and explore the solution from within our template. The following excerpt shows how we are able to retrieve the DTE:

C#:

IServiceProvider hostServiceProvider = (IServiceProvider)Host;

EnvDTE.DTE dte = (EnvDTE.DTE)hostServiceProvider.GetService(typeof(EnvDTE.DTE));

VB.NET:

Dim hostServiceProvider As IServiceProvider = Host

Dim dte As DTE = DirectCast(hostServiceProvider.GetService(GetType(DTE)), DTE)

Here, we use the Host property of the template to retrieve the EnvDTE.DTE instance. It is important to note that we are only able to retrieve the host from the template because an explicit property of our template directive at the top of the template, which looks like this:

<#@ template language="C#v3.5" hostSpecific="true" #>

Without hostSpecific, no Host property will exist because T4 won’t generate it when it compiles the template. For more information on the template directive, see Oleg Sych’s post on the subject. It is also important to note that when specifying the language in the template directive, if 'C#' is used then C# 2.0 will be used for compilation. If you wish to use the language features of 3.5, specify the language as 'C#v3.5' or 'VBv3.5'.

Following the retrieval of the EnvDTE.DTE instance, we are then able to locate the project

in which the template resides; as shown in the following excerpt:

C#:

EnvDTE.ProjectItem containingProjectItem = dte.Solution.FindProjectItem(Host.TemplateFile);

Project project = containingProjectItem.ContainingProject;

VB.NET:

Dim project As Project = dte.Solution.FindProjectItem(Host.TemplateFile).ContainingProject

Once we have obtained the project instance, we are able to traverse the project. We will explore how this occurs in greater detail later, when we look at the template implementation.

Generated Output

The MetadataGeneration.tt and MetadataGenerationVB.tt templates included in the download, produce metadata for an entire project. On generation, what results is a file containing various namespace blocks that include static classes representing our non-metadata classes and interfaces with the project. Property names, method names, and field names are represented as constants (or static properties if obfuscation support is enabled). Inner classes are represented as nested static classes. The generated output consists of classes that are internal static by default.

Generated classes are grouped into namespaces that match their non-metadata counterparts. For example, if there is a class called MyNamespace.Person, the generated output will be an internal static class called MyNamespace.Metadata.PersonMetadata. Of course all naming can be completely customized to suit your needs. It’s not necessary to place the generated classes in a sub-namespace, but I do so by default to avoid polluting the parent namespace.

The following are excerpts from the generated output of the downloadable C# and VB.NET demo projects:

C#:

using System.Windows;

using System;

using System.Linq;

using System.Linq.Expressions;

namespace DanielVaughan.MetaGen.Demo.Metadata

{

internal static class IPersonMetadata

{

public static class MemberNames

{

public const string Name = "Name";

}

public static PropertyPath NamePath { get { return new PropertyPath("Name"); } }

}

internal static class PersonMetadata

{

public static class MemberNames

{

public const string name = "name";

public const string Name = "Name";

public const string ObfuscationTest = "ObfuscationTest";

public const string OnPropertyChanged = "OnPropertyChanged";

}

public static PropertyPath NamePath { get { return new PropertyPath("Name"); } }

}

}

VB.NET:

Imports System.Windows

Imports System

Imports System.Linq

Imports System.Linq.Expressions

Imports System.Reflection

Friend Class IPersonMetadata

Public Class MemberNames

Public Const [Name] As string = "Name"

End Class

Public Readonly Shared Property NamePath() As PropertyPath

Get

Return new PropertyPath("Name")

End Get

End Property

End Class

Friend Class PersonMetadata

Public Class MemberNames

Public Const [OnPropertyChanged] As string = "OnPropertyChanged"

Public Const [Name] As string = "Name"

Public Const [_name] As string = "_name"

End Class

Public Readonly Shared Property NamePath() As PropertyPath

Get

Return new PropertyPath("Name")

End Get

End Property

End Class

Namespace DanielVaughan.MetaGen.VBDesktopClrDemo.Folder1.Metadata

Friend Class Folder1InterfaceMetadata

Public Class MemberNames

Public Const [Foo] As string = "Foo"

End Class

Public Readonly Shared Property FooPath() As PropertyPath

Get

Return new PropertyPath("Foo")

End Get

End Property

End Class

Friend Class Folder1SharedClassMetadata

Public Class MemberNames

Public Const [StringStaticProperty] As string = "StringStaticProperty"

Public Const [StringConstant] As string = "StringConstant"

End Class

Public Readonly Shared Property StringStaticPropertyPath() As PropertyPath

Get

Return new PropertyPath("StringStaticProperty")

End Get

End Property

End Class

End Namespace

With obfuscation enabled, the constants are replaced with static properties that rely on Linq Expressions for deriving the member names.

internal static class PersonMetadata

{

public static class MemberNames

{

public static string Name

{

get

{

return DanielVaughan.Metadata.ObfuscatedNameResolver.GetObfuscatedName(

"DanielVaughan.MetaGen.Demo.Person.Name",

x => {

Expression<Func<System.String>> expression =

() => default(DanielVaughan.MetaGen.Demo.Person).Name;

var body = (MemberExpression)expression.Body;

return body.Member.Name;

});

}

}

}

}

Here we see that we take the full name of a property ‘Name’ and use it as a key to a dictionary of obfuscated names. If this is the first time we are retrieving the name, we use a MemberExpression to resolve it. Once this is done, the dictionary is populated.

There are slight differences in how member names are derived when using the Linq

Expression approach, and they vary according to whether the member is static,

its parameter cardinality, and return type. You may notice this when exploring the generated output.

In order to enable WPF XAML binding support, PropertyPaths are generated for class properties. Generated PropertyPaths appear as static properties (required for binding), and in the case of obfuscation support enabled, use expression trees like their regular Member Name counterparts.

Please note that I have not yet implemented obfuscation support for the VB.NET version of the MetadataGenerationVB.tt

template.

Challenges with Silverlight Binding

There are obvious differences between databinding in WPF and Silverlight, in particular Silverlight’s absence of the x:Static binding attribute. Thus, I soon abandoned the implementation of compile time XAML validation in Silverlight. I tried to circumvent the absence of x:Static by binding the PropertyPath to a StaticResource. Alas, to no avail.

INPC string name code smell

I began this article espousing the virtues of compile time validation. But there are many other applications of generated metadata.

A highly desirable candidate for improvement is the INPC

(INotifyPropertyChanged) string name code smell. There has been much

discussion’s around this topic by the

WPF Disciples, and a great overview of the topic can be found on Karl Shifflett’s blog. Most solutions to the problem reside around using reflection in some shape or form, to derive the name of the property in order to signal that it is being changed. Thus avoiding mismatches between the name of the property and the string literal identifier. Unfortunately reflection can be slow, and while various techniques using reflection have been proposed, all contribute to decreased application performance. It now seems reasonable that a language extension for property change notification might be in order. But, as that may be some time coming, I have chosen to create the next best thing: a metadata generator.

C#:

Example 3 (traditional)

string name;

public string Name

{

get

{

return name;

}

set

{

name = value;

OnPropertyChanged("Name");

}

}

Example 4 (using generated metadata)

string name;

public string Name

{

get

{

return name;

}

set

{

name = value;

OnPropertyChanged(PersonMetadata.MemberNames.Name);

}

}

VB.NET:

Example 3 (traditional)

Private _name As String

Public Property Name() As String Implements IPerson.Name

Get

Return _name

End Get

Set(ByVal value As String)

_name = value

OnPropertyChanged("Name")

End Set

End Property

Example 4 (using generated metadata)

Private _name As String

Public Property Name() As String Implements IPerson.Name

Get

Return _name

End Get

Set(ByVal value As String)

_name = value

OnPropertyChanged(PersonMetadata.MemberNames.Name)

End Set

End Property

In Example 3 we see how a loosely typed string is used to specify the name of the property. There is a danger that if a modification is made to the property’s name, it will not be replicated in the argument value. If, like me, you use a third party tool for refactoring, then the situation may not be as dire, because these days most tools will check for matching string values as well. Yet, the risk remains that a mismatch will occur. There have been a number of solutions to this problem, and most have included reflection. But as mentioned, reflection comes at a cost: runtime performance.

In the Example 4 however, we see how our generated metadata come to the rescue, and is used to resolve the name of a property in a safe way. By using the generated metadata we have the safety of a constant, with the added benefit of improved performance by avoiding reflection.

Using the Template

To use the Metadata Generation template, simply include the downloaded MetadataGeneration.tt (C#) or MetadataGenerationVB.tt (VB.NET) file in your project. That’s it!

The MetadataGeneration.tt has a number of customizable constants that will allow you to prevent name collisions in your project, and to toggle obfuscation support.

const bool supportXamlBinding = true;

const bool supportObfuscation = false;

const string generatedClassAccessModifier = "internal";

const string generatedClassPrefix = "";

const string generatedClassSuffix = "Metadata";

const string generatedNamespace = "Metadata";

const int tabSize = 4;

The Demo Projects

I have included in the download three demo projects. Two of those are WPF Desktop CLR projects: one C# and the other VB.NET. The third project is a Silverlight C# project.

There is no difference between the MetadataGeneration.tt template present in the Silverlight project and the C# WPF project. The WPF VB.NET project is different however.

Figure: Unobfuscated Desktop CLR C# Demo Screenshot

I have attempted to demonstrate the obfuscation features of the Metadata Generation by assigning the metadata property name to a TextBlock as shown in the following excerpt:

NamePropertyBlock.Text = Metadata.PersonMetadata.MemberNames.ObfuscationTest;

We can see that the member ObfuscationTest of the Person class is resolved as "ObfuscationTest" in the unobfuscated version, and it is resolved as

"b" in the obfuscated version. All the while, a statically typed constant is used to represent the name.

Figure: Obfuscated Desktop CLR C# Demo Screenshot

Obfuscation Support

Obfuscation and string literals are unhappy bedfellows. More often than not,

obfuscating type names and member names must be disabled in order to support string literals placed in config files,

XAML, and in some cases in code, as with the INotifyPropertyChanged string literal property names (although I tried two obfuscators that appeared not to support property obfuscation at all anyway).

I have gone a little of the way in alleviating this problem. The Metadata Generation template is configurable to allow support for obfuscation. It is, however, experimental, and limited to non generic types at the moment. At runtime, expression trees are used to derive member names. Once a lookup occurs, names are cached to improve efficiency. We

can see an example of the generated output in the following excerpt:

public static string Address

{

get

{

return DanielVaughan.Metadata.ObfuscatedNameResolver.GetObfuscatedName(

"DanielVaughan.MetaGen.Demo.IPerson.Address",

x => {

Expression<Func<System.String>> expression =

() => default(DanielVaughan.MetaGen.Demo.IPerson).Address;

var body = (MemberExpression)expression.Body;

return body.Member.Name;

});

}

}

Likewise, for XAML binding support we also create XAML PropertyPaths that use the same mechanism:

public static PropertyPath AddressPath

{

get

{

return new PropertyPath(DanielVaughan.Metadata.ObfuscatedNameResolver.GetObfuscatedName(

"DanielVaughan.MetaGen.Demo.IPerson.Address",

x => {

Expression<Func<System.String>> expression =

() => default(DanielVaughan.MetaGen.Demo.IPerson).Address;

var body = (MemberExpression)expression.Body;

return body.Member.Name;

}));

}

}

Dotfuscator Community Edition was used to perform the obfuscation. The metadata was left unobfuscated,

as this version of Dotfuscator was not able to modify type names in the XAML.

Figure: Dotfuscator allows exclusion of types.

Figure: Obfuscation results.

While the Metadata Generation template comes equipped with obfuscation support for C#, I don’t recommend obfuscating member names. In my opinion it’s not worth the trouble, as it can raise issues at runtime when resolving types from configuration files.

Template Implementation

A statement block containing code to retrieve the EnvDTE.DTE instance, is located near the beginning of the template.

The DTE is the top level object in the Visual Studio automation object model, and allows us to retrieve file, class,

method information, and so on. Thanks go out to Oleg Sych

of the T4 Toolbox for demonstrating how to retrieve the EnvDTE.DTE from the template hosting environment.

Once we obtain the relevant EnvDTE.Project we are able to process the EnvDTE.ProjectItems (files and directories in this case) as the following excerpt shows:

C#:

EnvDTE.ProjectItem containingProjectItem = dte.Solution.FindProjectItem(Host.TemplateFile);

Project project = containingProjectItem.ContainingProject;

Dictionary<string, NamespaceBuilder> namespaceBuilders = new Dictionary<string, NamespaceBuilder>();

foreach (ProjectItem projectItem in project.ProjectItems)

{

ProcessProjectItem(projectItem, namespaceBuilders);

}

VB.NET:

Dim project As Project = dte.Solution.FindProjectItem(Host.TemplateFile).ContainingProject

Dim namespaceBuilders As New Dictionary(Of String, NamespaceBuilder)

Dim projectItem As ProjectItem

For Each projectItem In project.ProjectItems

Me.ProcessProjectItem(projectItem, namespaceBuilders)

Next

We then recursively process EnvDTE.CodeElements and directories in order to create an object model representing the project.

C#:

public void ProcessProjectItem(

ProjectItem projectItem,

Dictionary<string, NamespaceBuilder> namespaceBuilders)

{

FileCodeModel fileCodeModel = projectItem.FileCodeModel;

if (fileCodeModel != null)

{

foreach (CodeElement codeElement in fileCodeModel.CodeElements)

{

WalkElements(codeElement, null, null, namespaceBuilders);

}

}

if (projectItem.ProjectItems != null)

{

foreach (ProjectItem childItem in projectItem.ProjectItems)

{

ProcessProjectItem(childItem, namespaceBuilders);

}

}

}

int indent;

public void WalkElements(CodeElement codeElement, CodeElement parent,

BuilderBase parentContainer, Dictionary<string, NamespaceBuilder> namespaceBuilders)

{

indent++;

CodeElements codeElements;

if (parentContainer == null)

{

NamespaceBuilder builder;

string name = "global";

if (!namespaceBuilders.TryGetValue(name, out builder))

{

builder = new NamespaceBuilder(name, null, 0);

namespaceBuilders[name] = builder;

}

parentContainer = builder;

}

switch (codeElement.Kind)

{

case vsCMElement.vsCMElementNamespace:

{

CodeNamespace codeNamespace = (CodeNamespace)codeElement;

string name = codeNamespace.FullName;

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(generatedNamespace)

&& name.EndsWith(generatedNamespace))

{

break;

}

NamespaceBuilder builder;

if (!namespaceBuilders.TryGetValue(name, out builder))

{

builder = new NamespaceBuilder(name, null, 0);

namespaceBuilders[name] = builder;

}

codeElements = codeNamespace.Members;

foreach (CodeElement element in codeElements)

{

WalkElements(element, codeElement, builder, namespaceBuilders);

}

break;

}

case vsCMElement.vsCMElementClass:

{

CodeClass codeClass = (CodeClass)codeElement;

string name = codeClass.Name;

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(generatedNamespace)

&& codeClass.FullName.EndsWith(generatedNamespace)

|| (name.StartsWith(generatedClassPrefix) && name.EndsWith(generatedClassSuffix)))

{

break;

}

if (supportObfuscation && codeClass.Access == vsCMAccess.vsCMAccessPrivate)

{

break;

}

List<string> comments = new List<string>();

comments.Add(string.Format(

"/// <summary>Metadata for class <see cref=\"{0}\"/></summary>",

codeClass.FullName));

BuilderBase builder;

if (!parentContainer.Children.TryGetValue(name, out builder))

{

builder = new ClassBuilder(name, comments, indent);

parentContainer.Children[name] = builder;

}

codeElements = codeClass.Members;

if (codeElements != null)

{

foreach (CodeElement ce in codeElements)

{

WalkElements(ce, codeElement, builder, namespaceBuilders);

}

}

break;

}

case vsCMElement.vsCMElementInterface:

{

CodeInterface codeInterface = (CodeInterface)codeElement;

string name = codeInterface.Name;

if (name.StartsWith(generatedClassPrefix) && name.EndsWith(generatedClassSuffix))

{

break;

}

List<string> comments = new List<string>();

string commentName = FormatTypeNameForComment(codeInterface.FullName);

comments.Add(string.Format(

"/// <summary>Metadata for interface <see cref=\"{0}\"/></summary>",

commentName));

InterfaceBuilder builder = new InterfaceBuilder(name, comments, indent);

parentContainer.AddChild(builder);

codeElements = codeInterface.Members;

if (codeElements != null)

{

foreach (CodeElement ce in codeElements)

{

WalkElements(ce, codeElement, builder, namespaceBuilders);

}

}

break;

}

case vsCMElement.vsCMElementFunction:

{

CodeFunction codeFunction = (CodeFunction)codeElement;

if (codeFunction.Name == parentContainer.Name

|| codeFunction.Name == "ToString"

|| codeFunction.Name == "Equals"

|| codeFunction.Name == "GetHashCode"

|| codeFunction.Name == "GetType"

|| codeFunction.Name == "MemberwiseClone"

|| codeFunction.Name == "ReferenceEquals")

{

break;

}

var parentBuilder = (ClassBuilder)parentContainer;

parentBuilder.AddMember(codeFunction);

break;

}

case vsCMElement.vsCMElementProperty:

{

var codeProperty = (CodeProperty)codeElement;

if (codeProperty.Name != "this")

{

var parentBuilder = (ClassBuilder)parentContainer;

parentBuilder.AddMember(codeProperty);

}

break;

}

case vsCMElement.vsCMElementVariable:

{

var codeVariable = (CodeVariable)codeElement;

var parentBuilder = (ClassBuilder)parentContainer;

parentBuilder.AddMember(codeVariable);

break;

}

}

indent--;

}

VB.NET:

Public Sub ProcessProjectItem(ByVal projectItem As ProjectItem, _

ByVal namespaceBuilders As Dictionary(Of String, NamespaceBuilder))

Dim fileCodeModel As FileCodeModel = projectItem.FileCodeModel

If (Not fileCodeModel Is Nothing) Then

Dim codeElement As CodeElement

For Each codeElement In fileCodeModel.CodeElements

Me.WalkElements(codeElement, Nothing, Nothing, namespaceBuilders)

Next

End If

If (Not projectItem.ProjectItems Is Nothing) Then

Dim childItem As ProjectItem

For Each childItem In projectItem.ProjectItems

Me.ProcessProjectItem(childItem, namespaceBuilders)

Next

End If

End Sub

Public Sub WalkElements(ByVal codeElement As CodeElement, _

ByVal parent As CodeElement, ByVal parentContainer As BuilderBase, _

ByVal namespaceBuilders As Dictionary(Of String, NamespaceBuilder))

Dim codeElements As CodeElements

Dim builder As NamespaceBuilder

Dim name As String

Dim comments As List(Of String)

Me.indent += 1

If (parentContainer Is Nothing) Then

name = "global"

If Not namespaceBuilders.TryGetValue(name, builder) Then

builder = New NamespaceBuilder(name, Nothing, 0)

namespaceBuilders.Item(name) = builder

End If

parentContainer = builder

End If

Select Case codeElement.Kind

Case vsCMElement.vsCMElementNamespace

Dim codeNamespace As CodeNamespace = DirectCast(codeElement, CodeNamespace)

name = codeNamespace.FullName

If Not String.IsNullOrEmpty(generatedNamespace) _

AndAlso name.EndsWith(generatedNamespace) Then

Exit Select

End If

Dim tempBuilder As NamespaceBuilder

If Not namespaceBuilders.TryGetValue(name, tempBuilder) Then

tempBuilder = New NamespaceBuilder(name, Nothing, 0)

namespaceBuilders.Item(name) = tempBuilder

End If

codeElements = codeNamespace.Members

Dim element As CodeElement

For Each element In codeElements

Me.WalkElements(element, codeElement, tempBuilder, namespaceBuilders)

Next

Exit Select

Case vsCMElement.vsCMElementClass

Dim codeClass As CodeClass = DirectCast(codeElement, CodeClass)

name = codeClass.Name

If Not String.IsNullOrEmpty(generatedNamespace) _

AndAlso codeClass.FullName.EndsWith(generatedNamespace) _

OrElse (name.StartsWith(generatedClassPrefix) _

AndAlso name.EndsWith(generatedClassSuffix)) Then

Exit Select

End If

If supportObfuscation AndAlso codeClass.Access = vsCMAccess.vsCMAccessPrivate Then

Exit Select

End If

Dim tempBuilder As BuilderBase

comments = New List(Of String)

comments.Add(String.Format("''' <summary>Metadata for class <see cref=""T:{0}""/></summary>", codeClass.FullName))

If Not parentContainer.Children.TryGetValue(name, tempBuilder) Then

tempBuilder = New ClassBuilder(name, comments, Me.indent)

parentContainer.Children.Item(name) = tempBuilder

End If

codeElements = codeClass.Members

If Not codeElements Is Nothing Then

Dim ce As CodeElement

For Each ce In codeElements

Me.WalkElements(ce, codeElement, tempBuilder, namespaceBuilders)

Next

End If

Exit Select

Case vsCMElement.vsCMElementInterface

Dim codeInterface As CodeInterface = DirectCast(codeElement, CodeInterface)

name = codeInterface.Name

If (Not name.StartsWith("") OrElse Not name.EndsWith("Metadata")) Then

comments = New List(Of String)

Dim commentName As String = FormatTypeNameForComment(codeInterface.FullName)

comments.Add(String.Format("''' <summary>Metadata for interface <see cref=""T:{0}""/></summary>", commentName))

Dim b As New InterfaceBuilder(name, comments, Me.indent)

parentContainer.AddChild(b)

codeElements = codeInterface.Members

If (Not codeElements Is Nothing) Then

Dim ce As CodeElement

For Each ce In codeElements

Me.WalkElements(ce, codeElement, b, namespaceBuilders)

Next

End If

Exit Select

End If

Exit Select

Case vsCMElement.vsCMElementFunction

Dim codeFunction As CodeFunction = DirectCast(codeElement, CodeFunction)

If (codeFunction.Name <> parentContainer.Name _

AndAlso codeFunction.Name <> "ToString" _

AndAlso codeFunction.Name <> "Equals" _

AndAlso codeFunction.Name <> "GetHashCode" _

AndAlso codeFunction.Name <> "GetType" _

AndAlso codeFunction.Name <> "MemberwiseClone" _

AndAlso codeFunction.Name <> "ReferenceEquals") Then

DirectCast(parentContainer, ClassBuilder).AddMember(codeFunction)

End If

Exit Select

Case vsCMElement.vsCMElementVariable

Dim codeVariable As CodeVariable = DirectCast(codeElement, CodeVariable)

Dim parentBuilder As ClassBuilder = DirectCast(parentContainer, ClassBuilder)

parentBuilder.AddMember(codeVariable)

Exit Select

Case vsCMElement.vsCMElementProperty

Dim codeProperty As CodeProperty = DirectCast(codeElement, CodeProperty)

If (codeProperty.Name <> "this") Then

DirectCast(parentContainer, ClassBuilder).AddMember(codeProperty)

End If

Exit Select

End Select

Me.indent -= 1

End Sub

Iterating over ProjectItem CodeElements, we represent each with an instance of a specialized BuilderBase. Within the template there exists a type for each of the EnvDTE.vsCMElement Kinds that we wish to process.

Figure: Each EnvDTE.vsCMElement Kind is represented as an inner class in the template.

Each specialized BuilderBase class knows how to output itself. Once we have generated our model, we output our namespace representations to the resulting MetadataGeneration.cs file like so:

C#:

foreach (object item in namespaceBuilders.Values)

{

WriteLine(item.ToString());

}

VB.NET:

Dim item As Object

For Each item In namespaceBuilders.Values

Me.WriteLine(item.ToString)

Next

Thus, in C#, a namespace will output itself as a declaration and enclosing bracket, and then ask its children to output themselves. Simple really...

In order to support WPF XAML binding expression using the x:Static syntax, the template generates PropertyPath properties. The WPF binding infrastructure does not support binding to nested properties directly, so these were unable to be placed in an inner class, as I would have preferred for consistency. In any case, it means that our binding expressions end up being somewhat shorter.

Further Advantages

Interface Based Development

The metadata generation produces metadata, not only for classes, but also for interfaces. This is rather useful, because it allows us, for one thing, to not only dispense with using string literals for properties names in our bindings, but also to develop against interfaces in XAML. For example, in the sample download there is a class called Person,

which happens to implement an IPerson interface. We can bind to the Person class

metadata (PersonMetadata), but we also have the option to bind to the IPersonMetadata, as the following excerpt demonstrates:

<TextBox Text="{Binding Path={x:Static Metadata:IPersonMetadata.AddressPath}}"/>

One can imagine a scenario where there is no concrete implementation to begin with, and the GUI developer is given a set of interfaces that define the entities that will appear. Later, once the concrete entities have been developed, they are guaranteed to be compatible because they have implemented the GUI contract defined in the interface and declared in the XAML.

Another scenario where this might be useful is in a GUI first approach. The developer rapidly comes up with a prototype GUI design, all the while adding to the ViewModel interfaces. Later, the interfaces can be implemented. Moreover, a mocking system like Rhinomocks could be employed to mock the interfaces during development and testing.

Intellisense

When working with XAML, its common place to wire up Views to ViewModels using binding expressions.

It can be time consuming, incorrectly specifying the name of a property in a binding expression.

It means we must stop debugging, correct it, and restart your debugging session.

The absence of intellisense when using string literals means that sometimes we must resort to switching between files,

copying property names etc. Not much fun. Well, with generated metadata

we have the opportunity to forego this clumsiness. By using a third party add-in like Resharper,

Property names are available via intellisense right there in the XAML editor. That should save some time!

Conclusion

This article described how to use T4, and the Visual Studio automation object model API, to generate type information for an entire project. We have seen how generated metadata can be used to dispense with string literal property names in XAML binding expressions. We looked at how metadata can be used to promote runtime binding failures to compile time errors, improving reliability and developer efficiency. We saw how generated metadata can be used to solve the INotifyPropertyChanged string property name code smell,

without compromising performance. Finally we saw how Linq Expressions can be used to provide obfuscation support.

I’m excited about this approach, and I hope you will be too, because it marries compile time verification with runtime performance. Moreover, no Visual Studio add-in is required, as we are able to harness T4, Visual Studio’s built in template engine.

If you have any suggestions, such as ideas for other metadata information, please let me know.

I hope you find this project useful. If so, then I'd appreciate it if you would rate it and/or leave feedback below. This will help me to make my next article better.

History

August 2009

September 7 2009

- Provisioning for operator overloading.

October 3 2009

- Generates classes containing XAML metadata including x:Key properties.

- Property Path Generics bug fix

November 7 2009

- See here for a blog post outlining new features.

- JoinPath MarkupExtension allows concatenation of property paths in XAML to specify path for nested objects.

- Removed nested static class MemberNames from generated output as the nested class was incompatible with WPF XAML.