Introduction

Over the past decade or so, GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) have evolved from hardware specialized in (and dedicated to) rendering tasks to programmable high-performance computing devices that open new possibilities in term of numerical computations.

Numerous algorithms can use the vast processing power of GPUs to execute tasks faster and/or on larger data sets. Even in the days of the fixed, non-programmable graphical pipeline, graphics hardware could be used to speed up algorithms mostly related to image processing. For example, fixed pipeline functionality could be used to compute image difference, blur images, blend images and even assist in computing the average value of an image (or of an array of values).

Subsequently, programmable pipeline stages emerged giving even more flexibility to programmers. With the new possibilities offered by programmable stages, a broader class of algorithms could be ported to be executed on GPUs. A certain amount of ingenuity was often needed to convert algorithms so that they could be expressed in a suitable form to be computed by rendering something on the screen, often a screen-aligned quad.

Nowadays programmable GPUs support an even higher-level programming paradigm that turns them into GPGPUs (General-Purpose Graphics Processing Units). This new paradigm allows implementation of algorithms non-related to rendering by giving access to GPU computing hardware in a more generic, non-graphics-oriented way.

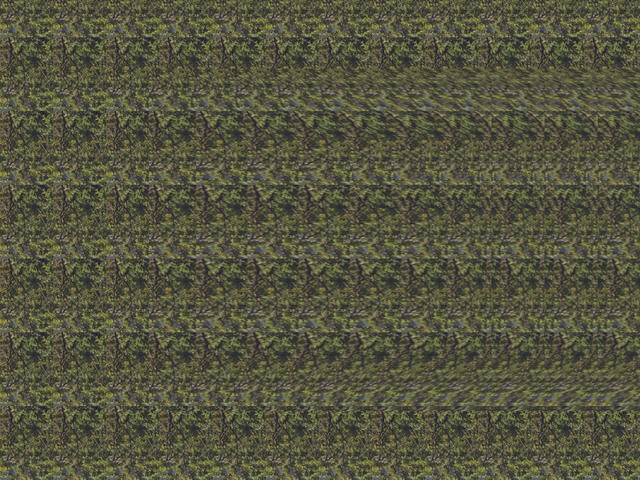

This article explores the new possibilities offered by GPGPU APIs using autostereogram generation as a case study where the programmable rendering pipeline can be extended by interoperating with GPGPU functionality. The depth buffer of a scene rendered using OpenGL is used as input for autostereogram generation on GPU using both OpenCL (GPGPU) kernels and OpenGL GLSL (programmable rendering pipeline) shaders to compute autostereograms without depth data having to be read back to the CPU.

Case Study : Autostereogram Generation

This article provides a brief presentation of autostereogram generation algorithm foundation and is not meant to review details of autostereogram generation. Please see references for further information.

Stereograms regained popularity when autostereograms became more common. Autostereograms are those single images that can be viewed as 3D scenes when looked at while not focusing on the image plane, most often behind the image plane.

3D scenes encoded in autostereograms can be difficult to see at first, but after a while, viewing those "secret" scenes hidden in autostereograms becomes very easy and effortless.

The algorithm implemented in this article is one of the simplest autostereogram generation algorithms. It basically repeats a tileable pattern (which can either be a tileable texture or a randomly generated texture) by changing the "repeat length" according to the z-depth of the pixel in the input depth map. So basically:

For each line of the output image:

Copy an entire line of the repeating texture (the tile)

For each pixel of the line in the input depth map:

Copy the color of the pixel located at one-tile-width pixels to left, minus an offset X

where X is 0 for maximum depth (furthest from eye)

and X is the maximum number of offset pixels (~30 pixels) for minimum depth (closest to eye)

Thus, the closer a pixel is supposed to be to the viewer, the shorter the repeating pattern is going to be. This is the basis of what tricks the eyes and brain into thinking that the image is three-dimensional. The output image width will be the sum of the repeating image and the input depth image widths to make room for the initial unalterned copy of the repeating image.

Instead of providing a more formal algorithm description, a CPU implementation that will describe it more precisely will later be examined while presenting a reference implementation for upcoming result and performance comparison.

References

General implementation overview

The following diagram represents the overall algorithm pipeline.

Render 3D scene

Rendering of the 3D scene is done using OpenGL Core Profile pipeline. The scene used as an example in this article contains a simple animated ball that bounces off the walls of an open box. A dynamic scene was chosen to provide more of a "real-time" effect from the different implementations.

The scene is rendered to textures using a framebuffer object in order to manipulate resulting data more easily. Using textures as render targets instead of the main backbuffer has some advantages:

- Output dimensions (width and height) become easier to control

- Problems when the rendering window is overlapped with other windows can be avoided

- Texture usage usually fits more naturally in this kind of post-processing pipeline

However, it would be possible to use standard backbuffer to render to and simply read back from this buffer.

Scene rendering generally outputs two buffers: a color buffer and a depth buffer. The latter is the part that is relevant for stereogram generation. There is thus no requirement to store colors when rendering the scene; only depth matters. Therefore, when creating the framebuffer object to which the scene will be rendered there is no need to attach a color texture. The following code shows creation of the framebuffer object with only a depth texture as its target.

glGenTextures( 1 , &mDepthTexture );

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , mDepthTexture );

glTexImage2D(

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

0 ,

GL_DEPTH_COMPONENT32 ,

kSceneWidth ,

kSceneHeight ,

0 ,

GL_DEPTH_COMPONENT ,

GL_FLOAT ,

0

);

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_MAG_FILTER , GL_LINEAR );

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_MIN_FILTER , GL_LINEAR );

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_S , GL_CLAMP_TO_EDGE );

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_T , GL_CLAMP_TO_EDGE );

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , 0 );

glGenFramebuffers( 1 , &mDepthFramebufferObject );

glBindFramebuffer( GL_FRAMEBUFFER , mDepthFramebufferObject );

glFramebufferTexture2D(

GL_FRAMEBUFFER ,

GL_DEPTH_ATTACHMENT ,

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

mDepthTexture ,

0

);

glBindFramebuffer( GL_FRAMEBUFFER , 0 );

Other initialization tasks are needed to perform scene rendering. Notably:

- Create, load and compile rendering shaders

- Create vertex buffers

In the main rendering loop, the following tasks must be performed:

- Set the framebuffer object as rendering target

- Set the shader program as active program

- Render the scene

In order to keep the article to a reasonable length these tasks will not be explained here. They are fairly common, straight-forward and not specific to this algorithm.

The following is a scene rendering generated by this program.

Horizontal coordinates computation

This is an interesting part of the algorithm as it is the one that will vary greatly between CPU and GPU implementations.

After this step, repeated tile texture coordinates will have been computed for each pixel of the final output image. Computing the vertical texture coordinate is not a major challenge as the tile simply repeats itself vertically without any variation. Vertical texture coordinates will not even be computed in this step, they will simply be trivially determined in the next step. The core of this stereogram generation algorithm is actually the computation of horizontal texture coordinates in the repeated tile for every output image pixel.

The result of this step will be a two-dimensional image of the same size as the final output stereogram where each pixel holds one single floating point value representing the horizontal texture coordinate. These floating point values will be constantly increasing from left to right where the fractional part will represent the actual coordinates (in a range between 0 and 1) and the integer part will represent the number of times the pattern has been repeated up to this point. This representation is used to avoid blending problems when looking up values. For example, if the algorithm samples between value 0.99 and 0.01, interpolation will yield a sampled value of around 0.5, which is completely wrong. By using value 0.99 and 1.01 instead, interpolation will yield a sampled value of around 1.0, which is coherent.

The algorithm pseudo-code listed above can be slightly modified to fit this intermediate step. After setting the first pixels to an entire line of repeated tile coordinates (i.e. increasing values between 0 and 1 to get a whole line of the tile), the lookup step can start by looking up one-tile-width number of pixels to the left, minus a value depending on the depth. So, in pseudo-code:

For each line of the output coordinate image:

Write the coordinates for the first line of the repeating tile

For each pixel of the line in the input depth map:

Sample the coordinate in the currently-written line one-tile-width pixels to left, minus an offset X

where X is 0 for maximum depth (furthest from eye)

and X is the maximum number of offset pixels (~30 pixels) for minimum depth (closest to eye)

Add 1 to this value so that result is constantly increasing

Store computed value in output coordinate image

More clarity with regards to implementation details will come out of the CPU implementation, as it is still fairly high-level while providing all working details.

Render stereogram

This last step takes the coordinate "image" and the repeated tile image as inputs and simply renders the final image by sampling the tile image at the appropriate place. It gets horizontal texture coordinates from input coordinate "image". It computes vertical texture coordinates from output pixel coordinates (the tile simply repeats itself vertically).

This sampling is done on the GPU using custom shaders. A screen-aligned quad is rendered and the following pixel shader is used to compute the final color in generated stereogram.

#version 150

smooth in vec2 vTexCoord;

out vec4 outColor;

uniform sampler2D uOffsetTexture;

uniform sampler2D uPatternTexture;

uniform float uScaleFactor;

void main( )

{

float lOffsetX = texture( uOffsetTexture, vTexCoord ).x;

float lOffsetY = ( vTexCoord.y * uScaleFactor );

vec2 lCoords = vec2( lOffsetX , lOffsetY );

outColor = texture( uPatternTexture , lCoords );

};

This concludes the algorithm overview. The next section describes the CPU implementation of the coordinates generation phase.

CPU implementation

The CPU implementation of the algorithm just covers generation of offsets (i.e. texture coordinates) from input depths. It is a simple C++ translation of the pseudo-code given above. It still is composed of three steps:

- First, depths are read back from GPU to CPU

- Then, offsets are generated from these depths

- Finally, offsets are written back from CPU to GPU

Step 1 : Reading input depths from GPU to CPU

After rendering the scene, depths are stored in a texture that lives on GPU. To access those depths for CPU implementation, depths must be fetched from GPU and stored in memory accessible from the CPU. A std::vector of floats is used to store those depths on the CPU side, as shown in the following code.

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , mDepthTexture );

glGetTexImage(

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

0 ,

GL_DEPTH_COMPONENT ,

GL_FLOAT ,

mInputDepths.data()

);

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , 0 );

Depths will then be stored in the vector of floating point values.

Step 2 : Processing

Generating offsets is simply applying the algorithm described above in pseudo-code and storing the result in a regular memory array. The following code shows this translation reading from mInputDepths to mOutputOffsets.

const int lPatternWidth = pPatternRenderer.GetPatternWidth();

const int lStereogramWidth = kSceneWidth + lPatternWidth;

for ( int j = 0; j < kSceneHeight; ++j )

{

for ( int i = 0, lCountI = lPatternWidth; i < lCountI; ++i )

{

float& lOutput = mOutputOffsets[ j * lStereogramWidth + i ];

lOutput = i / static_cast< float >( lPatternWidth );

}

for ( int i = lPatternWidth; i < lStereogramWidth; ++i )

{

float& lOutput = mOutputOffsets[ j * lStereogramWidth + i ];

const int lInputI = i - lPatternWidth;

const float lDepthValue = mInputDepths[ j * kSceneWidth + lInputI ];

const float lLookUpPos = static_cast< float >( lInputI ) + kMaxOffset * ( 1 - lDepthValue );

const int lPos1 = static_cast< int >( lLookUpPos );

const int lPos2 = lPos1 + 1;

const float lFrac = lLookUpPos - lPos1;

const float lValue1 = mOutputOffsets[ j * lStereogramWidth + lPos1 ];

const float lValue2 = mOutputOffsets[ j * lStereogramWidth + lPos2 ];

const float lValue = 1.0f + ( lValue1 + lFrac * ( lValue2 - lValue1 ) );

lOutput = lValue;

}

}

Step 3 : Writing output offsets from CPU to GPU

After generating the offsets, they must be sent back to GPU for final stereogram rendering. This operation is basically Step 1 in reverse and is shown in the following code.

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , mOffsetTexture );

glTexSubImage2D(

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

0 ,

0 ,

0 ,

lStereogramWidth ,

kSceneHeight ,

GL_RED ,

GL_FLOAT ,

mOutputOffsets.data()

);

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , mOffsetTexture );

Offsets will then have been written to GPU memory.

This concludes the algorithm CPU implementation. The biggest drawback from this approach is the need to exchange relatively large amount of data between CPU and GPU for every frame. Reading back image data from GPU for processing and then writing it back to GPU can be a considerable performance killer in real-time applications.

In order to prevent this issue, processing will be performed directly on GPU memory, avoiding the round-trip read-write between CPU and GPU. This approach is described in the following section.

GPU implementation

To avoid unwanted round-trips between CPU and GPU, depth data has to be processed directly on the GPU. However, the stereogram generation algorithm requires looking up values previously set within the same line of the output image. Reading from and writing to the same texture/image buffer is extremely unfriendly to conventional GPU processing approaches such as using fragment shaders.

It would be possible to use a "band" based approach where vertical bands would be rendered, from left to right, with each band no larger than the minimal look-up distance to the left. In the example provided in the source code, the repeating pattern width is 85 pixels, and the largest offset to that full look-up is 30 pixels (value of kMaxOffset), for a resulting maximum band width of 55 pixels. Because of the impossibility of reading at random locations from the texture being rendered to, two copies of the texture being rendered to would need to be kept: one to read from, and one to write to. Then what was just written would have to be copied to the other texture.

This approach requires two copies of the texture which is not optimal. Also, band width has a direct impact on the number of rendering passes which has a direct impact on performance. However, this width is dependent on the width of the repeating pattern, which can vary from one generation to the other, and on the maximum offset, which is a parameter that might benefit being able to be tuned in real-time. Having performance depending on varying parameters is far from ideal.

A more flexible approach than is possible using conventional programmable rendering pipelines is required. Enters OpenCL. The "General Purpose" part of this GPGPU API is especially important for this type of application. It will enable the use of GPU for more generic, less rendering-oriented algorithms and this flexibility will allow efficient use of GPU for stereogram generation.

First, a few modifications that need to be done to the rendering part of the CPU implementation will be shown. Then, creation of an OpenCL context able to share resources with an OpenGL context will be described. Finally, the OpenCL kernel used to generate stereograms will be presented along with elements needed to run it.

Modifications to rendering of the scene

The depth texture used by the CPU version of the algorithm cannot be used with the GPU implementation that was just presented. This texture has to be shared with the OpenCL context and OpenCL has limitations on formats of OpenGL textures it can access directly. According to the documentation for clCreateFromGLTexture2D which refers to a table of supported Image Channel Order Values, GL_DEPTH_COMPONENT32 is not a supported value for internal format of OpenGL textures that are to be shared with OpenCL. This is unfortunate because the internal representation of this format is very likely to be the same as the one to be used, but this lack of support problem can be circumvented.

In order to get a depth texture from the scene rendering step, a second texture will be attached to the frame buffer object. Remember that only one single depth texture was attached in the CPU version. This depth texture still needs to be attached so that it may serve as a depth buffer for depth test to work properly. However, another texture will be attached as a "color attachment" except that instead of receiving the color, it will receive the depth value. The following code shows how to create this texture and how to attach it to the frame buffer object.

glGenTextures( 1 , &mColorTexture );

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , mColorTexture );

glTexImage2D(

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

0 ,

GL_R32F ,

kSceneWidth ,

kSceneHeight ,

0 ,

GL_RED ,

GL_FLOAT ,

0

);

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_MAG_FILTER , GL_LINEAR );

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_MIN_FILTER , GL_LINEAR );

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_S , GL_CLAMP_TO_EDGE );

glTexParameteri( GL_TEXTURE_2D , GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_T , GL_CLAMP_TO_EDGE );

glBindTexture( GL_TEXTURE_2D , 0 );

glGenFramebuffers( 1 , &mDepthFramebufferObject );

glBindFramebuffer( GL_FRAMEBUFFER , mDepthFramebufferObject );

glFramebufferTexture2D(

GL_FRAMEBUFFER ,

GL_DEPTH_ATTACHMENT ,

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

mDepthTexture ,

0

);

glFramebufferTexture2D(

GL_FRAMEBUFFER ,

GL_COLOR_ATTACHMENT0 ,

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

mColorTexture ,

0

);

glBindFramebuffer( GL_FRAMEBUFFER , 0 );

A fragment shader is then needed to render depth to this "color attachment". It is fairly simple as shown in the following code:

#version 150

out vec4 outColor;

void main( )

{

float lValue = gl_FragCoord.z;

outColor = vec4( lValue , lValue , lValue , 1.0 );

}

These modifications will give a texture that is usable with clCreateFromGLTexture2D() for sharing with the OpenCL context, as will be shown in the following section.

OpenCL context creation

The following steps are usually performed in order to create an OpenCL context:

List OpenCL platforms and choose one (usually the first one).

List OpenCL devices on this platform and choose one (usually the first one).

Create an OpenCL context on this device.

However, for the stereogram generation algorithm implementation, care must be taken to allocate an OpenCL context that will be able to access OpenGL resources from existing context. Extra parameters will be given to OpenCL context creation routines to request a compatible context. This means that context creation can fail if, for example, OpenGL context was created on a different device than the one for which we are trying to allocate an OpenCL context. Therefore, creation steps need to be modified to enforce this compatibility requirement:

List OpenCL platforms.

For each platform:

List OpenCL devices on this platform

For each device:

Try to allocate a context

on this device

compatible with current OpenGL context

if context successfully created:

stop

Note that all platforms and devices must be looped over to ensure that the right context is found. The following shows the code performing this OpenCL context creation.

cl_int lError = CL_SUCCESS;

std::string lBuffer;

cl_uint lNbPlatformId = 0;

clGetPlatformIDs( 0 , 0 , &lNbPlatformId );

if ( lNbPlatformId == 0 )

{

std::cerr << "Unable to find an OpenCL platform." << std::endl;

return false;

}

std::vector< cl_platform_id > lPlatformIds( lNbPlatformId );

clGetPlatformIDs( lNbPlatformId , lPlatformIds.data() , 0 );

cl_platform_id lPlatformId = 0;

cl_device_id lDeviceId = 0;

cl_context lContext = 0;

for ( size_t i = 0; i < lPlatformIds.size() && lContext == 0; ++i )

{

const cl_platform_id lPlatformIdToTry = lPlatformIds[ i ];

cl_uint lNbDeviceId = 0;

clGetDeviceIDs( lPlatformIdToTry , CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU , 0 , 0 , &lNbDeviceId );

if ( lNbDeviceId == 0 )

{

continue;

}

std::vector< cl_device_id > lDeviceIds( lNbDeviceId );

clGetDeviceIDs( lPlatformIdToTry , CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU , lNbDeviceId , lDeviceIds.data() , 0 );

cl_context_properties lContextProperties[] = {

#if defined (WIN32)

CL_GL_CONTEXT_KHR , (cl_context_properties) wglGetCurrentContext() ,

CL_WGL_HDC_KHR , (cl_context_properties) wglGetCurrentDC() ,

#elif defined (__linux__)

CL_GL_CONTEXT_KHR , (cl_context_properties) glXGetCurrentContext() ,

CL_GLX_DISPLAY_KHR , (cl_context_properties) glXGetCurrentDisplay() ,

#elif defined (__APPLE__)

#if 0

CL_GL_CONTEXT_KHR , (cl_context_properties) CGLGetCurrentContext() ,

CL_CGL_SHAREGROUP_KHR , (cl_context_properties) CGLGetShareGroup( CGLGetCurrentContext() ) ,

#else

CL_CONTEXT_PROPERTY_USE_CGL_SHAREGROUP_APPLE , (cl_context_properties) CGLGetShareGroup( CGLGetCurrentContext() ) ,

#endif

#endif

CL_CONTEXT_PLATFORM , (cl_context_properties) lPlatformIdToTry ,

0 , 0 ,

};

for ( size_t j = 0; j < lDeviceIds.size(); ++j )

{

cl_device_id lDeviceIdToTry = lDeviceIds[ j ];

cl_context lContextToTry = 0;

lContextToTry = clCreateContext(

lContextProperties ,

1 , &lDeviceIdToTry ,

0 , 0 ,

&lError

);

if ( lError == CL_SUCCESS )

{

lPlatformId = lPlatformIdToTry;

lDeviceId = lDeviceIdToTry;

lContext = lContextToTry;

break;

}

}

}

if ( lDeviceId == 0 )

{

std::cerr << "Unable to find a compatible OpenCL device." << std::endl;

return false;

}

cl_command_queue lCommandQueue = clCreateCommandQueue( lContext , lDeviceId , 0 , &lError );

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

{

std::cerr << "Unable to create an OpenCL command queue." << std::endl;

return false;

}

After the OpenCL context is created, OpenCL buffer objects (of type cl_mem) can now be created to represent OpenGL textures to be shared. Memory will not be allocated for those buffers, they will simply be aliases of the same underlying buffers as the OpenGL textures, allowing OpenCL to read from and write to those buffers.

In order to create those references to OpenGL textures, the clCreateFromGLTexture2D function is used, as shown here:

mDepthImage = clCreateFromGLTexture2D(

mContext ,

CL_MEM_READ_ONLY ,

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

0 ,

pInputDepthTexture ,

&lError

);

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

return false;

mOffsetImage = clCreateFromGLTexture2D(

mContext ,

CL_MEM_WRITE_ONLY ,

GL_TEXTURE_2D ,

0 ,

pOutputOffsetTexture ,

&lError

);

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

return false;

Note that this function is deprecated by clCreateFromGLTexture in OpenCL 1.2, but clCreateFromGLTexture2D will still be used so that this application can run on OpenCL-1.1-only systems.

The buffers can now be used as regular OpenCL buffers that will be processed by an OpenCL kernel which will be described in the following section.

Kernel design, implementation and execution

The purpose of this section is not to go into OpenCL concepts and syntax details, but to present elements specific to this problem. In the context of this stereogram generation algorithm, two factors have a major impact on kernel design: first, there is a data dependency for pixels on the same line and second, it is not possible for a kernel to read from and write to the same image buffer within the same kernel execution.

How much data should the kernel process?

Kernels are designed to run on a subset of the data to be processed in order for them to be run in parallel by the multiple computing units available in OpenCL-capable devices. A very popular design choice for image processing algorithms implemented in OpenCL is to have one kernel instance run on each pixel of the image, which allows a great deal of parallelism. However, the stereogram generation algorithm shows a problematic data dependency on pixels on the same line to the left of any pixel to be processed. Therefore, designing the kernel to be run once per line instead of per pixel is better suited for the problem at hand so that the proposed kernel will handle an entire line at a time.

How can reading from and writing to the same buffer be avoided?

Another problem somewhat related to this data dependency issue is the impossibility to read from and write to the same image buffer within an OpenCL kernel, just like OpenGL textures cannot be sampled from and written to within the same render pass. However, results from already processed pixels are required to compute upcoming pixels. The algorithm will need to be adapted.

A simple observation can help: a value never needs to be looked up further than the width of the repeating image. Therefore, a local buffer of the same width can be used to hold the last computed offsets. By using this local buffer to write to and to read from at will as a circular buffer, that read/write problem can be avoided. When an offset is computed, the kernel always reads from the local buffer and writes the result back to both the local buffer and the output image. Thus there is never a need to read from the output image, which solves the problem.

Those types of adaptations are common when implementing algorithms using GPGPU APIs. These APIs usually offer different capabilities and present different restrictions in comparison to CPU implementations, notably with regards to synchronization primitives. Modifications such as this one can be necessary to port the algorithm as in this case. However, they can also be optimizations that allow the kernel to run faster, for example by having more efficient memory access patterns. This must be kept in mind when porting algorithm from CPU to GPGPU: the translation is not always direct even for simple problems like this one.

Having dealt with those design issues, it is now possible to come up with an implementation for this kernel. The following code illustrates the concerns discussed above.

const sampler_t kSampler =

CLK_NORMALIZED_COORDS_FALSE

| CLK_ADDRESS_CLAMP_TO_EDGE

| CLK_FILTER_NEAREST;

__kernel void Stereogram(

__write_only image2d_t pOffsetImage ,

__read_only image2d_t pDepthImage

)

{

float lBuffer[ kPatternWidth ];

const int2 lOutputDim = get_image_dim( pOffsetImage );

const int lRowPos = get_global_id( 0 );

if ( lRowPos >= lOutputDim.y )

return;

for ( int i = 0 ; i < kPatternWidth; ++i )

{

const float lValue = ( i / (float) kPatternWidth );

lBuffer[ i ] = lValue;

const int2 lOutputPos = { i , lRowPos };

write_imagef( pOffsetImage , lOutputPos , (float4) lValue );

}

for ( int i = kPatternWidth ; i < lOutputDim.x; ++i )

{

const int2 lLookupPos = { i - kPatternWidth , lRowPos };

const float4 lDepth = read_imagef( pDepthImage , kSampler , lLookupPos );

const float lOffset = kMaxOffset * ( 1 - lDepth.x );

const float lPos = i + lOffset;

const int lPos1 = ( (int) ( lPos ) );

const int lPos2 = ( lPos1 + 1 );

const float lFrac = lPos - lPos1;

const float lValue1 = lBuffer[ lPos1 % kPatternWidth ];

const float lValue2 = lBuffer[ lPos2 % kPatternWidth ];

const float lValue = 1 + lValue1 + lFrac * ( lValue2 - lValue1 );

lBuffer[ i % kPatternWidth ] = lValue;

const int2 lOutputPos = { i , lRowPos };

write_imagef( pOffsetImage , lOutputPos , (float4) lValue );

}

};

This kernel code must now be compiled by the OpenCL drivers before it can be run. Doing so is like compiling any OpenCL kernel:

const char* lCode = kKernelCode;

std::ostringstream lParam;

lParam << "-D kPatternWidth=" << pPatternWidth << " -D kMaxOffset=" << kMaxOffset;

cl_program lProgram = clCreateProgramWithSource( mContext , 1 , &lCode , 0 , &lError );

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

return false;

lError = clBuildProgram( lProgram , 1 , &mDeviceId , lParam.str().c_str() , 0 , 0 );

if ( lError == CL_BUILD_PROGRAM_FAILURE )

{

size_t lLogSize;

clGetProgramBuildInfo(

lProgram , mDeviceId , CL_PROGRAM_BUILD_LOG , 0 , 0 , &lLogSize

);

std::string lLog;

lLog.resize( lLogSize );

clGetProgramBuildInfo(

lProgram ,

mDeviceId ,

CL_PROGRAM_BUILD_LOG ,

lLogSize ,

const_cast< char* >( lLog.data() ) ,

0

);

std::cerr << "Kernel failed to compile.\n"

<< lLog.c_str() << "." << std::endl;

}

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

return false;

cl_kernel lKernel = clCreateKernel( lProgram , "Stereogram" , &lError );

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

return false;

A few parameters are defined as constants that will be used by all executions of this kernel. It would have been possible to use a different strategy to allow runtime tweaking of the kMaxOffset parameter for example. The value of this variable could have been passed as a parameter to the kernel function, but in this application it is kept constant so it was defined as a kernel-compile-time constant.

The only thing left for the kernel to be ready to run is to bind the kernel function parameters, i.e. the input and output image buffers:

lError = clSetKernelArg( mKernel , 0 , sizeof( mOffsetImage ) , &mOffsetImage );

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

return false;

lError = clSetKernelArg( mKernel , 1 , sizeof( mDepthImage ) , &mDepthImage );

if ( !CheckForError( lError ) )

return false;

These parameters can be set once for all kernel executions because they do not change. The kernel is always run on those buffers so those parameters can be set at initialization instead of in the main loop.

Running of the kernel inside the main loop requires three simple steps:

- Synchronize OpenGL textures to make sure OpenGL has finished writing to them before using them with OpenCL

- Run the OpenCL kernel

- Synchronize OpenGL textures to make sure OpenCL has finished writing to them before returning them to OpenGL

The following code shows how to perform these tasks:

cl_mem lObjects[] = { mDepthImage , mOffsetImage };

cl_int lError = 0;

glFinish();

const int lNbObjects = sizeof( lObjects ) / sizeof( lObjects[0] );

lError = clEnqueueAcquireGLObjects(

mCommandQueue , lNbObjects , lObjects , 0 , NULL , NULL

);

CheckForError( lError );

lError = clEnqueueNDRangeKernel(

mCommandQueue ,

mKernel ,

1 ,

NULL ,

&mSize ,

&mWorkgroupSize ,

0 ,

NULL ,

NULL

);

CheckForError( lError );

lError = clEnqueueReleaseGLObjects(

mCommandQueue , lNbObjects , lObjects , 0 , NULL , NULL

);

CheckForError( lError );

lError = clFinish( mCommandQueue );

CheckForError( lError );

Offsets will thus have been computed on the GPU without needing to transfer data back from the GPU to the CPU and then again from CPU to GPU.

This concludes the GPU implementation of the algorithm. It showed that by combining OpenGL and OpenCL, expensive round-trips between CPU memory and GPU memory can be avoided while still maintaining enough flexibility to implement non-trivial algorithms.

The Code

The code provided in this article shows the implementation of the concepts presented herein. It is not designed to be particularly reusable. It is meant to be as simple as possible, as close as possible to OpenGL and OpenCL API calls and with the least amount of dependencies possible in order to clearly illustrate the object of the article. In fact, this demo application was initially developed in a personal framework that was then stripped in order to arrive at the current minimal application.

This demo was run successfully on Intel and NVidia hardware. It was not tested on AMD hardware but it should run as is or worst-case scenario with only minor modifications. It was run on Windows Vista and 7 (compiled with Microsoft Visual Studio), Ubuntu Linux (compiled with GCC) and OS X Mountain Lion (compiled with GCC).

The application supports three modes that can be switched alternately by using the space bar. The first one is the regular rendering of the scene using very basic lighting shading. The second one is the stereogram generation CPU implementation. The third one is the stereogram generation GPU implementation.

On Intel HD Graphics 4000 hardware, the first mode (regular rendering) runs at around 1180 frames per second. The second mode (CPU implementation) runs at around 11 frames per second. The third mode (GPU implementation) runs at around 260 frames per second. Even though frames per second are not necessarily the most precise performance metrics, they still give an appreciation of results. It is clear that by avoiding the round-trip from GPU to CPU and by using the parallel computation power of the GPU, significant performance improvements can be achieved.

Conclusion

The stereogram generation algorithm presented in this article is a great opportunity to demonstrate the power of using GPGPU to interact with the rendering pipeline. It was shown that a part of the algorithm that would be either impossible to implement using only the programmable rendering pipeline (GLSL shaders) or would result in a very inefficient implementation can be implemented quite easily using OpenCL to access OpenGL textures and process them in ways that would not really be GLSL-friendly.

By providing flexible means to implement more complex algorithms directly on GPU, interaction between rendering pipeline (OpenGL) and GPGPU APIs (OpenCL) presents an elegant and efficient solution to GPU data processing for interesting (i.e. difficult) problems. It gives developers tools to address such problems with less programming gymnastics that is often required to implement algorithms on the GPU and even opens the door to more possibilities than the ones offered by the regular programmable rendering pipeline.

That being said, this implementation could probably still be much improved. OpenCL is not a magic wand that "automagically" achieves portable performance. Optimizing OpenCL implementation can be a beast of its own... So it would be interesting to take this demo application further in order to see how its simple implementation could be improved to achieve even greater performance. Furthermore, OpenGL Compute Shader would also be an interesting path to explore to solve similar problems.

References