Introduction

This example project comes with two classes that you might be interested in - clsSharpZipLib and clsDotNetZip. These are wrappers for the core functionality of these two libraries - because as user friendly as they try to be (specially DotNetZip), there is still quite a bit of code that goes into using them. If you're like me, you won't want to have to rewrite it over and over for every project you work on. And they block, so you'll need to create some threads if you don't want to lock up your UI... and then there's the issue of tracking progress.

These classes handle it all for you. They offer a handy callback you can use to track progress, get error messages, etc. This example project shows you how to use it all.

As nice as this is, it's really not the point of this article though. This article is a comparison of the two zip libraries, because it seems that while there are quite a few opinions on them out there, the hard data I found was either misleading or just plain wrong. Using this example project, you will be able to determine for yourself which library is right for you.

Background

Recently, I found myself needing to add limited zip functionality to the project I was working on. My application needed to zip files as fast as possible, but would never be called upon to open the zip files it created. Years ago, I had written a wrapper for #ZipLib, and so I dug it out - and looked on in chagrin at what I'd produced back then... it needed a rewrite.

So I found myself rewriting this wrapper... and struggling to figure out why #ZipLib was SO SLOW. At first, I thought is was my code, but Googling for a solution I discovered lots of people asking about the same thing. It seems that this is just how #ZipLib is. If you use it to compress your zip files (as opposed to adding them to a zip archive uncompressed), expect it to take about twice as long as winrar or winzip, even at the lowest compression level.

I found some reviews on DotNetZip - the other free solution, and was disappointed to read that even though people thought it was much easier to work with, it was a little slower. Luckily, this wasn't true.

In fact, I eventually found a Stack Overflow page where one of the posters wrote about DotNetZip's ParallelDeflateOutputStream class. This class uses multiple threads to compress files, increasing the compression speed by using all the cores in your system.

After much testing, the project I built to refine and test the wrapper class I would eventually use became this - an application designed to compare the performance of each library.

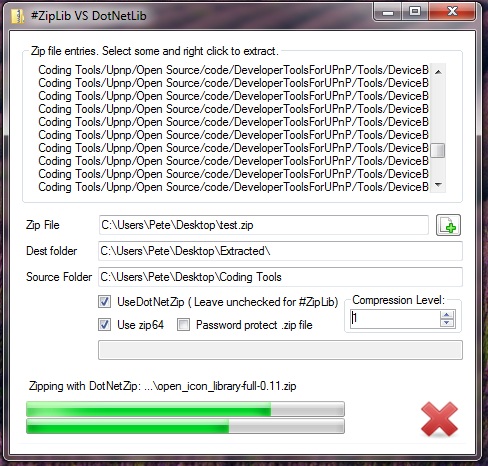

If you choose to run this app, you will be able to create zip files, list their contents (in a primitive way), choose files to extract, set compression levels (if you choose to use compression at all), set the password, choose to use Zip64 (or not), and most importantly choose which of the two libraries to use to preform your zip operation by clicking a check box.

Every operation is timed, and the results are displayed after the zip / unzip is complete.

I developed this test application on my Windows 7 x64 quad core laptop. It has 4 gig of ram, and a 5400 RPM hard drive. During my testing, I used a source folder containing almost 7000 files totalling 873MB.

On this machine, DotNetZip uses all 4 cores while compressing large files, and compresses my test source folder in less then half the time it takes #zipLib. The actual average times are:

#ZipLib: Compression level 1, Creates a 684 MB file, completes in 1 minute, 45 seconds.DotNetZip: Compression level 1, creates a 690 MB file, completes in 45 seconds.

I think it's interesting to note here that it takes WinRar 1 minute and 5 seconds, on the average, to compress these same files.

When it comes to extracting these files, #ZipLib beats DotNetZip by about 15 seconds.

Again, these are average times. It was hard for me to write 1 minute, 45 seconds here for #ZipLib, because there were test runs where it actually took almost 3 minutes. The times listed above were observed after repeated zipping and extracting, when window's file cache was working as well as it possibly can.

I realize that my testing is just that - my testing, run on my hardware and that these numbers will be different elsewhere.

If you're interested, I invite you to download the example project and do some testing of your own. If you choose to post your results here, we'll all have a better understanding of how these two libraries stack up against each other.

I realize that most people arriving at this page probably came here for a quick and easy way to add zip functionality to their VB.NET app - so I took the time to separate the functionality of each library into its own wrapper class. If you decide you want to use DotNetZip, just copy clsDotNetZip into your project, add a reference to Ionic.zip.dll, have a look at the example project (or a look below - it's very simple) to see how to implement it, and your off. For #ZipLib, it's clsSharpzipLib and ICSharpCode.SharpZipLib.dll.

Using the Code

Instantiation

Instantiating one of the classes looks like this:

Dim zipLib As clsSharpZipLib = New clsSharpZipLib(zipPath, _

clsSharpZipLib.ZipAccessFlags.Create, _

1024 * 1024, _

nudCompression.Value, _

cbZip64.Checked, _

tbPassword.Text, _

100, _

AddressOf zipCallback)

Now, I think this is pretty straight forward. But then I wrote the class, and I would - so I'll explain what we have here.

zipPath - is a string containing the path of the zip file you want to open, or the location of one you would like to create.clsSharpZipLib.ZipAccessFlags.Create - This is a public enum you'll find in the class. It's a file access flag - it tells the class what you'll be doing with the zip file.1024 * 1024 - This is the size of the buffer you'd like this class to work with.nudCompression.Value - This is a numeric up down control I use to specify the compression level in the example project. Valid values are 0 - 9.cbZip64.Checked - Yep - This is a checkbox control. If you've checked it, then you'll be compressing using Zip64.tbPassword.Text - Self explanatory.100 - This is the callback update speed in milliseconds. I'm passing the value 100 here, so the callback in this example project will fire once every 100 milliseconds, containing data you can use to update your user interface about the current operation.AddressOf zipCallback - zipCallback is the address of the callback Sub in the example project. All the good stuff happens off the UI thread, so if you want information about how your zip operation's going, you'll have to supply one of these.

In the example project, I track the overall progress in bytes, and the progress of the current file being processed in bytes. Doing it like this just seems like the right way to do it, and makes for smooth and accurate progress bars.

The Callback

This is what the callback sub in the example app looks like:

Private Sub zipCallback(ByRef zipData As clsCompareLibs.ZipData)

Static lastName As String

If Me.InvokeRequired Then

Me.Invoke(callback, zipData)

Else

With zipData

If .fileList IsNot Nothing AndAlso .fileList.Count > 0 Then

Dim names As New List(Of String)

currentEntries.Clear()

For Each entry As clsCompareLibs.ShortEntry In .fileList

names.Add(entry.name)

currentEntries.Add(entry)

Next

Me.lbFileList.Items.AddRange(names.ToArray())

Me.lblFileName.Text = "Complete."

Try

zipLib.Close()

Catch ex As Exception

End Try

me.Cursor = System.Windows.Forms.Cursors.Default

Else

If lastName <> zipData.currentFileName Then

pbCurrentFile.Value = 0

lastName = zipData.currentFileName

End If

lblFileName.Text = .operationTitle

If .currentFileName <> "" Then lblFileName.Text += ": ...\" & _

Path.GetFileName(.currentFileName)

If .currentFileBytesCopied > 0 AndAlso .totalBytes > 0 Then

pbCurrentFile.Value = (.currentFileBytesCopied / .currentFileLength) * 100

pbTotalBytes.Value = (.totalBytesCopied / .totalBytes) * 100

pbCurrentFile.Refresh()

pbTotalBytes.Refresh()

End If

If .complete Then

zipLib.Close()

If .cancel Then

lblFileName.Text = "Canceled."

pbCurrentFile.Value = 0

pbTotalBytes.Value = 0

Else

endTime = Now

If endTime.Subtract(startTime).TotalSeconds > 60 then

lblFileName.Text = "Complete. This operation took " & _

endTime.Subtract(startTime).Minutes.ToString() & _

" minutes, and " & endTime.Subtract(startTime).Seconds.ToString() _

& " seconds."

Else

lblFileName.Text = "Complete. This operation took " & _

endTime.Subtract(startTime).TotalSeconds.ToString("N1") & _

" seconds."

End If

End If

tsbZipFiles.Visible = True

tsbZipFiles.Enabled = True

tsbListZipEntries.Visible = True

tsbCancel.Visible = False

me.Cursor = System.Windows.Forms.Cursors.Default

End If

If .errorMessage <> "" Then

MsgBox("" & .errorMessage, MsgBoxStyle.Critical, "Zip Example App")

me.Cursor = System.Windows.Forms.Cursors.Default

End If

End If

End With

End If

End Sub

You'll see that each time the callback fires, you get the state of the current operation. Everything you need to track progress is there - the current file's name, the number of bytes currently transferred for that file, the total number of bytes being copied, the current total transferred, the title of the operation (i.e.: "Extracting", or "Zipping"), error messages, etc.

Specifying Files to be Zipped / Unzipped

I tried to make the class interface as much like a generic list as possible. That being written, to add files to a zip file you use the Add() method. Add() will accept a string or a generic list(Of string). You can pass it the path of a single file, or a folder in each entry. If you're passing a folder, you can also specify if you want this class to recourse sub-directories.

To get a list of entries in the zip file, use ListZipEntries(). The ListZipEntries() method doesn't return a list. Everything with this class happens off the UI thread. The list is returned in the callback. See above how to retrieve it.

To extract files from a zip, you call - you guessed it - Extract(). The Extract() method has three overloads: you can pass it a single string containing the entry to be extracted and a target folder, a list(Of String) containing entries to be extracted and a target folder, or a List(Of ShortEntry) and a string containing the target folder.

A List(Of ShortEntry) is what you get back when you call ListZipEntries(). ShortEntries are just structures containing the entry name, its size, and its index. Passing Extract() a List(Of ShortEntry) will improve performance.

But Isn't There More?

I'm sure you're aware that these libraries do more then just zip and unzip files. DotNetZip alone can create self extracting zip files, break zip files up into parts, and much more. I didn't try to wrap all the functionality of each library... it would have taken me forever - and remember, all I needed to start with was a way to quickly zip some files for my current project. If you want more functionality than this, you'll need to add it yourself.

Points of Interest

The relevance of these two libraries, and this article may actually be in question. As of .NET 4.5, Microsoft is including a ZipArchive class as part of the framework. I had a quick look at it on MSDN, and as of this writing it isn't anywhere near as flexible as DotNetZip, though I'm sure that will change over time. What may keep these libraries relevant is superior performance and functionality that Microsoft doesn't offer, though I think this will put #ZipLib out of the running as its compression performance isn't great and it seems to be abandoned by the developer.

I guess we'll see what happens.

History

- 08/04/2012 - Fixed a crash if the list zip entries button is clicked without a zip file selected

- 08/05/2012 - Rebuilt the project with option

explicit and option strict on